Gender integration. Troops upset with their service's byzantine classification system. Mind-dulling training sessions worthy of ridicule, part of a system clogged by mounds of red tape. Problems adjusting to civilian life after the fight ends.

Modern military headlines, all. But also, apparently, topics on the mind of the War Department in the mid-1940s as officials sought methods to entertain and inform troops who'd been away from home for long stretches, busy winning World War II.

How do you reach, and engage, such a large and diverse audience on these types of topics? One solution: A Broadway-style musical, produced by men who would become entertainment-industry icons, with some assembly required – packets with music, scripts and stage directions would be shipped with detailed instructions to units far afield, where troops would scrounge up the necessary materials and perform the shows themselves.

Production of the so-called "blueprints" ramped up as the war wound down. As troops came home, some pieces went unfinished. The completed ones all but vanished, overcome by other forms of traveling entertainment. War zones like Korea and Vietnam, and the soldiers in them, weren't exactly clamoring for musical theater.

Cast members, including current and former service members, prep for their January performances of the "Blueprint Specials" at the USS Intrepid Museum.

Photo Credit: Ashley Garrett

But when a Broadway director stumbled upon four of the blueprints, he decided the time was right for a reprisal – with some help from a handful of veteran military talent.

"I couldn't believe nobody knew about these, given the stature of the artists involved," said Tom Ridgely, co-founder of the New York-based Waterwell ensemble and director of the "Blueprint Specials," a performance pulled from four original blueprints that will debut Jan. 6 for a

limited run in a period-perfect location: A hangar bay at the USS Intrepid Museum.

"It seemed like a no-brainer," said Ellen Silbermann, director of public programs at the museum. "It was something that we had a unique venue to really make it special."

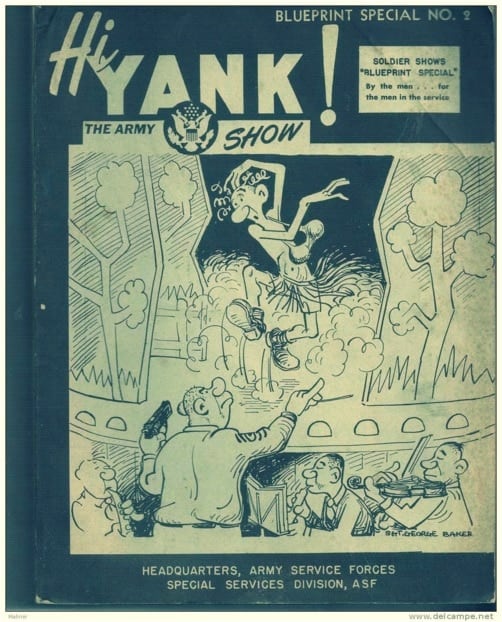

BLUEPRINT IN A BOX

Ridgely's Waterwell had been working on a piece from an era that makes the blueprints look modern – retelling the story of the Greek hero Ajax. But the "Blueprint" production came less from that connection and more from a random earworm.

During dinner one night, "I got the opening song from 'Guys and Dolls' stuck in my head," Ridgely said. He decided to\ look up other pieces from the composer, Frank Loesser; his Wikipedia bio pointed toward musicals he'd done for the Army, in addition to the 1942 song "Praise the Lord and Pass the Ammunition" that hit No. 1 on the chart the next year.

That triggered what amounted to a treasure hunt: One blueprint had been digitized and could be viewed online. Another was available through a library loan. A third was in the New York Performing Arts Library – as was a fourth, which a Waterwell intern discovered uncatalogued in a box when sent to make copies of the third one.

An original "blueprint" instruction book.

Photo Credit: Courtesy of Waterwell

Research turned up a forgotten source of the era’s musical theater treasure. Loesser’s writing went along with choreography from José Limón (1908-1972), whose dance company has outlived its founder. Plans for a blueprint with an opening number from Oscar Hammerstein never came completely together, nor did a proposed "All-Negro Show" with input from Duke Ellington and Count Basie, Ridgely said.

A PBS documentary briefly featured a single recording of one of the blueprints, and some of the pieces had been reviewed by theater critics in test shows before deployment, but evidence of prior performances was thin.

Ridgely, fittingly, soldiered on. He reached out to Victor Hurtado, an Army veteran whose long tenure with Army Entertainment included time with the long-running, recently discontinued Soldier Show. Hurtado came aboard as a producer and helped find some veterans to populate a cast of about three dozen.

"I read it and I said to Victor, 'I'm the drill sergeant, right?' said James Edward Becton, a former Soldier Show performer who auditioned for the touring group for Hurtado in South Korea, next to a generator. "And Victor said, 'Yeah.' "

THE ROAD TO SHOWTIME

So, on Dec. 8, Becton and Hurtado found themselves with the rest of the cast in a third-story rehearsal space on 42nd Street, a few blocks from the Times Square recruiting station. Becton worked through multiple speaking roles, portraying an aging southern colonel and, yes, a drill sergeant, working with the actor portraying Sad Sack, one of the show's leads.

Hurtado was quick to note that the civilian-military crew is a meritocracy, something he said brings a greater level of pride to the performers than a veteran-only crew would.

"My service got me in the door," said Sandra Lee, a disabled combat veteran who served eight years in the Army in reserve and active roles, including an Iraq deployment in 2003. She plays Sue, a character who, like most of the rest of the female characters, is a member of the then-novel Women's Army Corps.

"It's interesting what kind of role the women played back then," Lee said. "It's kind of come full circle, in a way," with the recent integration of women into combat units.

Lee and Becton are among about a dozen members of the cast with strong veteran ties – including Emily McAleesejergins, who missed the bulk of rehearsal because of her active-duty duties as a singer with the West Point Band.

The rest of the cast, which includes two Tony Award nominees, played with dialects and worked out notes and harmonies for the musical numbers. They’ll get an assist with the dancing portion thanks to dancers from Limón’s studio.

The tone is unmistakably of the era, with cast members singing about their best gals and jokingly about "raking in all the dough" from their stint in service. Ridgely plans for the musical's look to be of the time, as well, which creates some issues, even though instructions for one

of the blueprints state the scenery "can be knocked together in a jiffy from scrap materials found in even the loneliest outpost."

"When it calls for 48 World War II-era Class B uniforms, that's tricky," Ridgely said.

James Edward Becton, an Army veteran, joins fellow cast members for a Dec. 8 rehearsal of the "Blueprint Specials."

Photo Credit: Ashley Garrett

FAMILIAR FOUNDATIONS

While the actors, directors and producers polished the 40s veneer and the military-speak, their source material brought out some very familiar themes:

- WAC members discuss the role of women in the military and receive training on what social activities are permitted with male soldiers of various ranks.

- The "Classification Blues" allows soldiers to list all the ways the Army has managed to neglect their private-sector skills when doling out jobs.

- The Army’s version of sex ed, in which a flustered instructor uses somewhat less-than-technical terminology involving birds, bees and "hanky panky."

- Privacy issues that pre-date social media by decades, in the form of the song "Why Do They Call a Private a Private?" once recorded by Ethel Merman, a stage and-screen star whose career took flight in the 1930s and may have peaked for a new generation when she played a traumatized lieutenant in 1980’s "Airplane."

- An entire blueprint – "OK, USA!" – dedicated to re-introducing soldiers to their homeland after many suffered through extensive deployments.

Despite time's passage, the piece "gives you sort of a closer look at what it's like to serve," said ensemble member Brad Bong, who enlisted in the Army National Guard in 2003 and spent time in reserve and active roles. Because the creators were in service themselves, "they had an

intimate idea of what that's like."

Some tropes cross generational boundaries – "I knew a guy sort of like Sad Sack at Fort Benning," Bong recalled – but Ridgley and many in the civilian/military cast are concentrating on something that has been lost, they say.

"There was a moment when there was this absolute closeness between the arts and the military," he said. "And I don't feel that today. … Everybody knew someone who served. You weren't in another category."

Service members or veterans/veterans groups interested in tickets can email allysonproduction@gmail. com for production details.

Kevin Lilley is the features editor of Military Times.