Kurt Chew-Een Lee spearheaded preparations in December 1950 for 500 Marines to embark on a daring rescue mission. The first lieutenant’s undertaking came during the vicious Battle of Chosin Reservoir, as tens of thousands of Chinese troops streamed in from North Korea and threatened to cut off an American unit.

Traversing five miles across treacherous mountainous terrain, Marines battled against blizzard conditions that cut visibility to almost zero. Temperatures oftentimes plummeted to 30 below.

Despite bullet wounds and a broken arm suffered during a previous engagement, Lee, along with his unit, went on to relentlessly engage the enemy while under intense fire. By the end, their exploits would help preserve a crucial evacuation route for American troops fighting as United Nations forces. Approximately 8,000 men were saved from certain death or imprisonment at the hands of the Chinese.

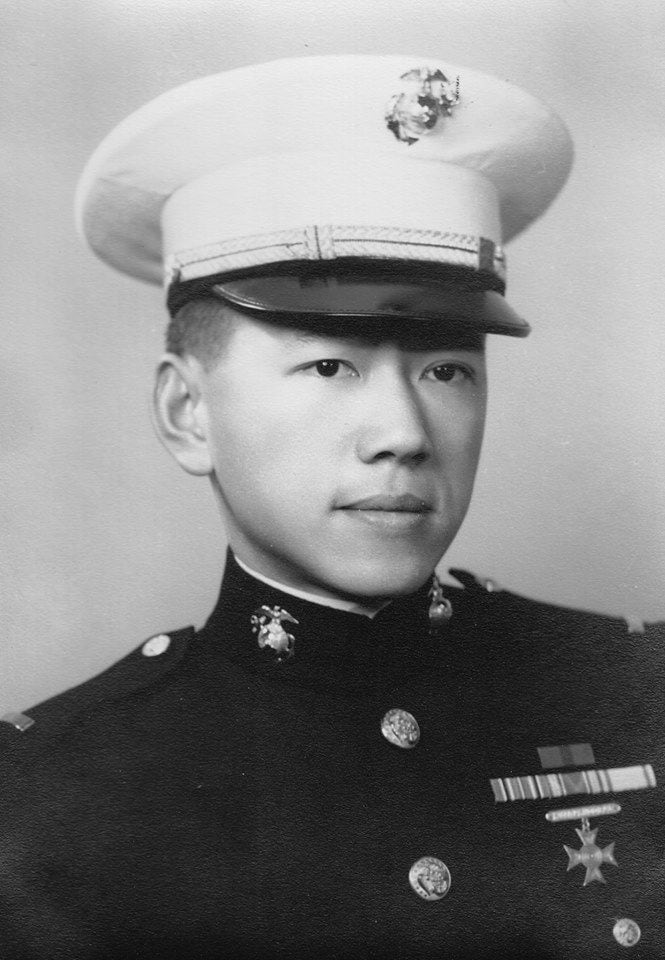

Born on January 21, 1926, in San Francisco, the slight-of-build Lee — all of 5-feet-6 inches tall and roughly 130 pounds — is believed to be the first Asian-American officer in Marine Corps history. Still, Lee “brought outsized determination to the battlefield,” according to an account in the New York Times.

Lee, who enlisted in the Marines at the end of World War II, told the Los Angeles Times in 2010 that he identified most with the Corps due to its reputation of being first into battle.

“I wanted to dispel the notion about the Chinese being meek, bland and obsequious,” he said.

Lee was assigned during WWII as a Japanese language instructor in San Diego. Swallowing his disappointment at not being sent to the Pacific, he chose to remain in the Marine Corps after the war and commissioned as an officer in 1946.

As the U.S. entered into the Korean War in June 1950, Lee was placed in charge of a machine gun platoon that was tasked with advancing deep into North Korean territory.

Before the fighting began, many of Lee’s fellow Marines questioned whether he was capable of killing Chinese soldiers. Behind his back some even used racial epithets, calling him a “Chinese laundry man.”

For Lee, the questioning of his devotion to his nation was ludicrous.

“I would have … done whatever was necessary,” he told the Los Angeles Times. “To me, it didn’t matter whether those were Chinese, Korean, Mongolian, whatever — they were the enemy.”

Lee’s Chinese ancestry, however, came as a boon on the night of November 2, 1950. Conducting a solo reconnaissance mission amid heavy snowfall, he began to lob grenades and fire rounds at the enemy with the intent of exposing the location of Chinese soldiers who were firing upon his men.

Undetected, Lee crept up on the enemy outpost and utilized his working knowledge of Mandarin to confuse the enemy combatants, who hesitated briefly as Lee called out in their native tongue, “Don’t shoot, I’m Chinese.”

That pause allowed just enough time for Lee’s unit to reposition and drive back the Chinese. For this, Lee was awarded the Navy Cross, the second-highest honor a Marine can receive.

“Despite serious wounds sustained as he pushed forward, First Lieutenant Lee charged directly into the face of the enemy fire and, by his dauntless fighting spirit and resourcefulness, served to inspire other members of his platoon to heroic efforts in pressing a determined counterattack and driving the hostile forces from the sector,” his citation reads.

Less than a month later, while Lee was still recovering in a field hospital from a gunshot wound to the arm he sustained during the early November fighting, the Chinese launched its Second Phase Offensive — aimed at driving the United Nations out of North Korea. Tens of thousands of Chinese forces converged on the mountainous region near the Chosin Reservoir, overrunning the nearly 8,000 American troops stationed there.

Undeterred by his wounds, Lee “and a sergeant left the hospital against orders, commandeered an Army jeep and returned to the front” to link up with the 1st Marine Battalion, according to the New York Times. Lee’s arm was still in a sling.

Using only a compass to traverse the snowy mountain terrain, Lee and his 500 Marines managed to find and reinforce the surrounded Americans, repeatedly driving back Chinese soldiers, according to the Times, and ensuring “the vastly outnumbered Americans were able to retreat to the sea.”

The fighting was so fierce that roughly 90 percent of Lee’s rifle company was killed or wounded, but thanks to Lee’s indefatigable efforts, the evacuation route remained open.

“Certainly, I was never afraid,” Lee told the Washington Post in 2010. “Perhaps the Chinese are all fatalists. I never expected to survive the war. So I was adamant that my death be honorable, be spectacular.”

Lee survived the war, retiring from the Marines in 1968 after serving in Vietnam as an intelligence officer. In addition to the Navy Cross, Lee was awarded a Silver Star and two Purple Hearts.

The men he commanded never forgot their officer.

“I didn’t care what color he was,” Ronald Burbridge, a rifleman in his unit in Korea, said in an interview for a 2010 Smithsonian documentary.

“I have told him many times, thank God that we had him.”

Claire Barrett is the Strategic Operations Editor for Sightline Media and a World War II researcher with an unparalleled affinity for Sir Winston Churchill and Michigan football.