source GAIA package: Sx_MilitaryTimes_M6201310306100016_5675.zip Origin key: Sx_MilitaryTimes_M6201310306100016 imported at Fri Jan 8 18:18:10 2016

Camo patterns and combat uniforms across the services have gotten so out of control and expensive that members of Congress are renewing the fight for a single "purple" combat uniform to be worn across the military.

Camo patterns and combat uniforms across the services have gotten so out of control and expensive that members of Congress are renewing the fight for a single "purple" combat uniform to be worn across the military.

House lawmakers have gone so far as to propose a law requiring a common combat uniform no later than October 2018.

But what does this mean for the Navy working uniform Type I, those blue-and-gray duds that technically aren't worn in combat but boast an aquaflage pattern?

It could certainly mean the end of the uniform, according to one senior Navy official, who sees this latest action from Congress as a solution to another of the sea service's problems: the fact those NWUs burn robustly and melt when exposed to fire, posing a significant injury risk to sailors.

If the Defense Department is compelled by Congress to cull the uniform numbers, it's logical the services will determine the best one for wear, reasoned this official, who asked not to be identified because he was not authorized to discuss it publicly.

Assuming this uniform will have flame-resistant properties, it could solve the Navy's fire-risk problem. And, as a DoD-wide initiative, the uniform is likely to come at a bargain price, he said.

"We as a service already concluded that it's prudent to get fire-retardant clothing items in the hands of every sailor at sea," the official said, anticipating significant costs to go along with it.

This is only the latest strike against the NWU, which has found itself in the cross hairs in recent months:

Navy Times broke the story last year that high-level officials were mulling ditching the Type I in favor of the Type II and Type III NWUs, the desert and woodland variants, with a more comfortable design for sailors working in hot climates.

Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Jon Greenert went on record in May saying the Navy will look at switching to a lighter-weight NWU fabric as a result of sailor complaints about Type Is, though he told Navy Times a new option had to be affordable.

This year, two Navy working groups were created to assess the fire risk for sailors at sea and the uniforms and FR gear they wear. The first group focused on organizational clothing but also made some recommendations about the NWU.

The group said that the service could adopt Defender M, a fire-retardant fabric fielded by the Marine Corps and Army since 2006, for use in an NWU at-sea variant. But it also made an interesting proposal to differentiate the new NWU from the old one: Make it a solid-blue uniform. So long, aquaflage, at least while you're at sea.

The second working group is zeroing in on the Type Is and standard-issue coveralls, so sailors can probably expect still more theories of how to fix the NWU.

Uniform madness

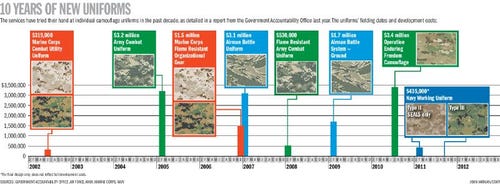

There are 10 versions of combat uniforms now and more under development, with total development and fielding costs running into billions of dollars. Lawmakers see it as a symbol of waste and inefficiency at DoD.

"Doggone it, we can save some money if we stop playing in the sand," said Rep. Bill Enyart, D-Ill., a Vietnam veteran and retired Air National Guard major general who is spearheading the latest effort. "This is something we can stop and should."

The bill would permit variants for geography, such as desert or woodland patterns. Exceptions also would be allowed for head wear, footwear and special operations units. But the result would be most troops wearing the same combat uniform when deployed to the same location or environment.

If it becomes law, the measure certainly affects the Navy's two "tactical" uniforms, the NWU Type II and III, the desert and woodland variants.

But those uniforms are only worn by a fraction of sailors, and aren't issued uniforms.

It's unclear how the NWU Type I will be affected by the bill, and the question is likely to send Navy lawyers scrambling. In the past, the Navy has been able to dodge high-spending scrutiny by arguing that the NWU is not a "combat uniform."

It could all come down to the exact words Congress uses in trying to rein in the services' spending.

In early 2010, the Government Accountability Office was asked by Congress for the first time to investigate the extent of the camo uniform proliferation, and specifically wanted to know the total price tag to taxpayers.

The law stated that the GAO would "conduct an assessment of the ground combat uniforms and camouflage utility uniforms currently in use in the Department of Defense."

But only the cost of the development of the NWU Types II and III were included in the study, as Navy officials were able to convince the GAO that the Type I uniform shouldn't be included.

GAO officials told Navy Times in an exclusive interview about the study at the time that the Navy persuaded them not to include the blueberries because they were not technically a "camouflage utility uniform."

Navy officials told GAO that the Type I wasn't meant to camouflage anyone onboard ship and instead was just a "camouflage stylized uniform."

The GAO was apparently satisfied with that argument, and the report doesn't show the expense to research, develop and initially roll out the NWU Type I: $226 million.

Next steps

Capitol Hill's effort to require a common combat uniform has a long way to go before it becomes law. While the full House is likely to go along with its Armed Services Committee's proposal, Senate approval still would be needed.

The outlook there is unclear; the Senate Armed Services Committee has yet to begin drafting its version of the defense bill. But at least one influential senator supports a common combat uniform.

Sen. Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., a lawyer in the Air Force Reserve, said the idea makes sense. "I'm now in favor of having some common standards," Graham, who has had several brief combat-zone assignments, said in an interview. "As much as I love the Air Force, I've grown to understand we have too many designs. I have four different sets at home because I try to make sure I deploy with the uniform everyone else will be wearing. It seems excessive."

Graham will be in a position to push the issue forward; he will be one of the chief negotiators this year, when House and Senate lawmakers meet to reconcile differences between their respective versions of the defense bill.

Prohibiting the services from spending billions of dollars developing and fielding new uniforms is one way to reduce the Pentagon's nearly $500 billion budget in an era of sequestration, said Rep. Tammy Duckworth, D-Ill., who helped get the amendment attached to this year's defense bill.

It "cuts down on the waste of ... unnecessary duplication of the camouflage our men and women so proudly wear," Duckworth, an Iraq War veteran who is in the Illinois National Guard, told the House Armed Services Committee.

"There are a lot of things that could be done with that money, including expanding programs for personnel, families and weapons programs," she said. "If this were a time when we didn't have any budget issues, I would not be doing this."

A decade of churn

A common combat uniform is not an especially new idea. As recently as 2001, all four services shared a single camouflage pattern and design. The green version was known as the battle dress uniform, and the brown variant was known as the desert camouflage uniform.

The Navy, in fact, was the last service to use the uniforms, ditching them finally last summer in the Type II and III transition.

The changes began in 2002, when the Marine Corps adopted its digital-style Marine Pattern camouflage, or MARPAT. Its wash-and-wear fabric saved the Corps money on starch and laundry services, and gave Marines a distinctive look that reinforced their self-propelled image as an elite force.

That started a new fashion trend. Camouflage, once used to prevent detection and reduce troops' vulnerability, became a way for the services to distinguish themselves. The Marines unwittingly triggered a cascade of new uniform initiatives by the other services, many of them fielded with great fanfare but later deemed to be failures.

The Army spent $3.2 million to developed an "Army Combat Uniform," but Army officials said it did not perform well in Afghanistan, so today soldiers there are wearing a different camouflage pattern designed for that environment. The Army is planning to unveil yet another new combat uniform soon.

The Air Force spent several years and about $3.2 million to design a unique tiger-stripe pattern that was fielded in 2007, but the Air Force later decided it was a flawed design and ordered deployed airmen to wear the Army version.

The Navy spent more than the other services, $8.39 million between 2005 and 2009, to develop desert and woodland patterns for the Type IIs and Type IIIs. But the service also curtailed its use of the desert pattern when the Marines protested that it looked too much like MARPAT.

The Army could save $82 million if it partnered with another service for developing and buying a new uniform, according to the GAO report.

Yet some defense experts say uniform costs are a drop in the overall military budget bucket and Congress should be tackling the hard issues that would save much more.

"They are shooting at the wrong target," said Arnold Punaro, a member of the Defense Business Board, which advises the Pentagon on cost-saving measures and business practices. "I would hope that Congress would spend more time in oversight of things of much more significance in terms of savings, like the overhead at the Defense Department and reforming the acquisitions process or dealing with the runaway costs of military health care."

A simmering issue

Congress has been inching forward on this issue for several years. The 2010 Defense Authorization Act ordered the GAO to study the costs and performance of combat uniforms, which led to the substantive report that was unveiled last September.

And the same law ordered the Pentagon to "establish joint criteria for future ground combat uniforms." The deadline for developing those joint criteria is in late June.

Yet defense officials say they have no current plans to dictate to the services what kind of camouflage pattern they should use.

A Pentagon panel known as the Joint Clothing and Textiles Governance Board is finalizing the "joint criteria," which are limited to textile standards such as fire and insect resistance and field life, defense officials say. Those criteria were approved in February and formal instructions on how to implement them will be provided to the service chiefs this summer, Pentagon spokesman Mark Wright said.

But the board opted not to include a specific camouflage pattern among the standards, in part because the individual services have historically had control over designing their uniforms to fit their missions, said a defense official familiar with the process.

However, panel members are aware of the proposed law and may have to consider adding a specific camouflage pattern before the joint criteria are formally issued this year, the official said.

Despite the growing interest on Capitol Hill in the idea of a common combat uniform, some lawmakers are reluctant to get involved in an area that has traditionally been left to the individual services to manage.

Sen. Richard Burr, a North Carolina Republican who initially supported the GAO review of combat uniforms, said he's not keen to have Congress micromanaging that process. Asked if he would support the proposed House legislation, Burr said: "No, no. Hopefully, that is something DoD can figure out on its own."

Future of the NWU

Meanwhile, the Navy continues its work investigating what should be done about the fact both the NWU Type Is and the standard-issue coveralls cannot stand up to flame.

The recommendations of the first working group determined that every sailor needs at least two pairs of flame-resistant coveralls at sea. Surface forces and carriers will be getting new pairs of FR coveralls within nine months and there's a three-year plan for a coverall that can span all communities. The second working group will recommend whether the NWU should remain a shipboard uniform.

If the Navy decides to create a standard-issue FR uniform, it will not come cheap. The first working group estimated that a flame-resistant NWU would cost double. And there are still thousands of Type Is in stock.

According to the Defense Logistics Agency, as of June 5, the Navy has on hand 265,643 Navy working uniform Type I trousers and 216,824 blouses valued at $10.2 million and $9 million, respectively. Each year, it must purchase 219,000 trousers and 221,000 blouses to maintain those stocks.

The Navy official who spoke with Navy Times said lawmakers' latest step could be a safety net as the service seeks safer uniforms. For that reason, he said, the service should not sidestep the camo debate, as it did for the GAO report.

"From a cost perspective, this could help us simply by complying with the law and not trying to maintain the argument that the Type Is don't belong in the discussion because they're only a camouflage-style uniform and not designed for ground combat use."

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/archetype/VWNM5FPR4VC6JBBPO3VQTU54D4.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/archetype/VCIH6X4C5FHFPFJ6I4NG43OVKU.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/archetype/FGETHDCP7FGIVBP6345WI7CYLQ.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/archetype/ICE6ILJ27VAJBLU5SZZZCKVGLE.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/archetype/XHCUSJLAJVBIJBGQRFK3AFPZCI.png)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/archetype/KV7P2WGEKRCW7MIDAP63R5GPDI.jpg)