WASHINGTON ― The House voted Thursday to repeal the 2002 authorization of military force against Iraq, a step that supporters say is necessary to constrain presidential war powers even though it is unlikely to affect U.S. military operations around the world.

With an endorsement from the White House and Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, repeal of the Iraq-focused measure appears to have its best chance of passage in years. Schumer vowed to bring the matter to the Senate floor this year, after a committee mark up planned for next week.

The House voted 268-161, with 49 Republicans joining 219 Democrats in favor. The legislation was sponsored by Rep. Barbara Lee, D-Calif.

The war authorization, originally focused on the fight against then-Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein, has been used to justify action on a range of groups since. House Foreign Affairs Committee Chairman Gregory Meeks, D-N.Y., argued the AUMF was “vulnerable to being abused,” given Iraq’s proximity to other global hotspots.

“Repeal is crucial because the executive branch has a history of stretching the 2002 AUMF’s legal authority,” said House Foreign Affairs Committee Chairman Gregory Meeks, D-N.Y. “It has already been used as justification for military actions against entities that had nothing to do with Saddam Hussein’s Ba’athist’s dictatorship.”

RELATED

The House Foreign Relations Committee’s top Republican, Rep. Michael McCaul voted against the measure, arguing the Biden administration hadn’t adequately consulted with the Pentagon, State Department, Iraq, allies or Congress.

The move, “sends a dangerous message of disengagement that could destabilize Iraq, embolden Iran, which it will, and strengthen al-Qaeda and ISIS in the region. We would avoid such dangers by taking up a repeal, but a replacement simultaneously,” said McCaul, of Texas.

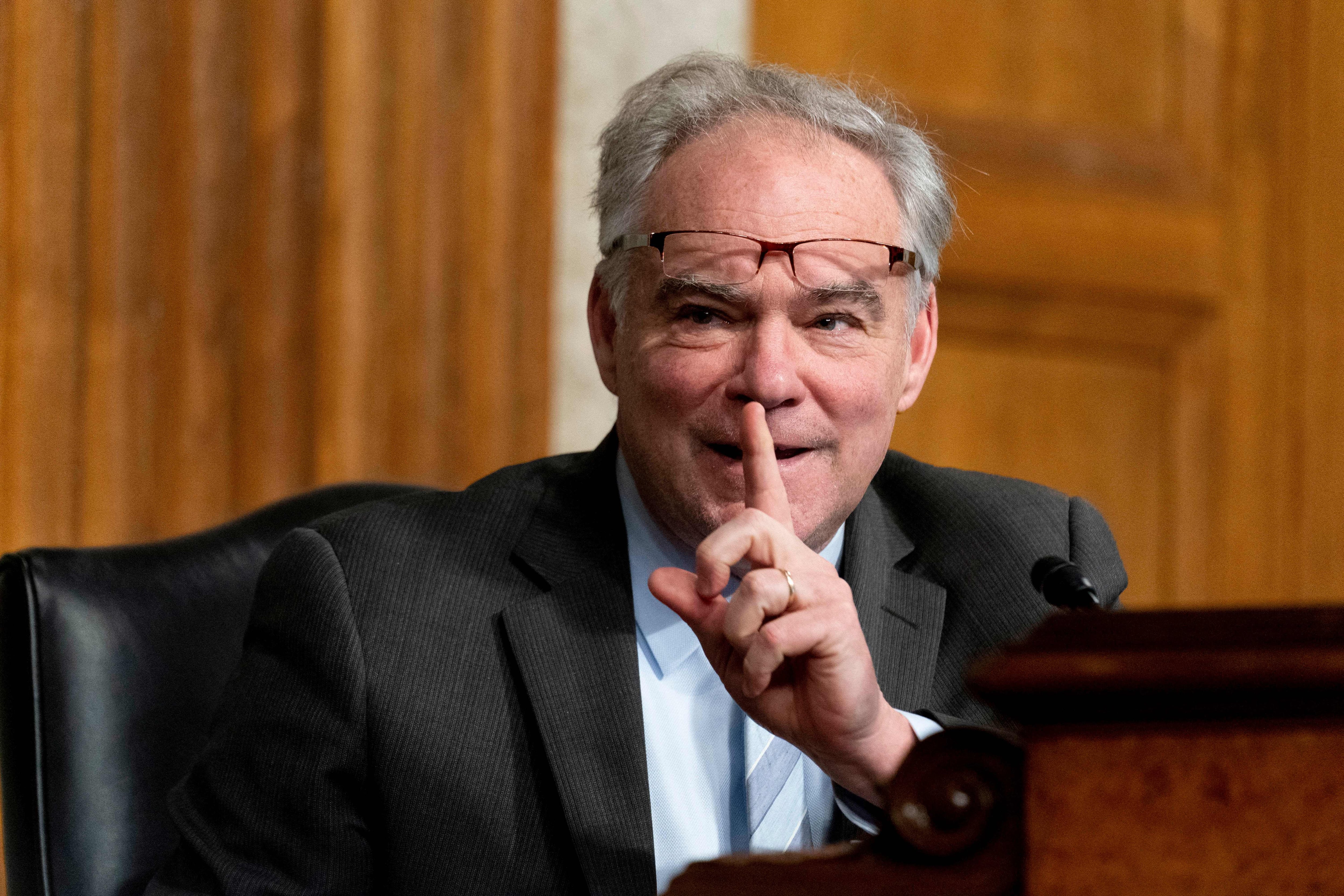

The Senate bill from Sens. Tim Kaine, D-Va., and Todd Young, R-Ind., would also repeal the Iraq-focused 1991 authorization. If the Senate passes it, the two chambers will then have to work out any differences in their two bills and vote on a final product before it can go to President Joe Biden’s desk to be signed into law.

Speaking with reporters Wednesday, Kaine said he hopes the 2002 AUMF repeal would become an amendment to the larger annual National Defense Authorization Act later this year. He wants to spark talks this summer to revise the 2001 AUMF by its 20th anniversary in September and to rewrite the 1973 War Powers Resolution, which mandates the president get Congress’s approval before sending troops into action abroad.

Though there’s a bipartisan appetite to reclaim Congress’s war powers, the 2002 repeal effort is seeing resistance from some top Senate Republicans. Senate Republican Leader Mitch McConnell announced his opposition Thursday, calling it repeal “reckless,” and asking how repeal would impact U.S. counter-terror missions, cyber operations and support for Kurdish and Arab forces.

“The AUMF is important in Iraq because it provides authorities for U.S. forces to defend themselves from a variety of real exigent threats,” said McConnell, of Kentucky. “It’s arguably even more important in Syria, where our personnel are present against the wishes of the brutal Assad regime supporting local Kurdish and Arab forces and conducting strikes against ISIS.”

The Senate Armed Services Committee’s ranking member, Sen. Jim Inhofe, R-Okla., opposes AUMF repeal. He said Wednesday he’s inclined to oppose its inclusion in the NDAA, but he’d be open to discussing it with SASC Chair Jack Reed, D-R.I.

“It just confuses the bill, in my opinion, though I might lose that one,” Inhofe said. “It’s one of those things I hope we wouldn’t have to deal with in our defense authorization bill because you’ll have enough things in there.”

At least one influential Republican, Senate Foreign Relations Committee ranking member Jim Risch, of Idaho, said Wednesday he was not ready to announce a stance. Among Republicans overall, there’s “there’s a lot of internal debate,” with “legitimate arguments on both sides,” but no consensus yet, he said.

RELATED

But Young was optimistic on Wednesday.

“The politics just got a lot easier,” he said. “Democrats will want to be supportive of their party’s president, and Republicans may, as things happen around here, not entirely trust the foreign policy objectives of this administration. So you may gain a few votes on each side on account of that dynamics.”

The White House said earlier in the week that it supports the legislation, stressing that no ongoing military activities rely upon the 2002 authorization. It also said Biden is committed to working with Congress to replace war authorizations with a narrow framework meant to ensure the U.S. can protect Americans against terrorist threats.

In a floor speech Wednesday, Schumer said the measure did not mean the U.S. would abandon Iraq, its people or the shared fight against the Islamic State. Instead, he said it would, “eliminate the danger of a future administration reaching back into the legal dustbin to use it as a justification for military adventurism.”

He pointed to the Washington-directed airstrike against Iranian Gen. Qassim Soleimani in 2020 as an example.

The Trump administration justified the act in a memo citing a president’s constitutional authority to protect national interests from an attack, as well as the 2002 AUMF. The administration’s shifting explanations included an unsupported claim that Soleimani was plotting an imminent attack on U.S. embassies.

“There is no good reason to allow this legal authority to persist in case another reckless commander-in-chief tries the same trick in the future,” Schumer said.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.

Joe Gould was the senior Pentagon reporter for Defense News, covering the intersection of national security policy, politics and the defense industry. He had previously served as Congress reporter.