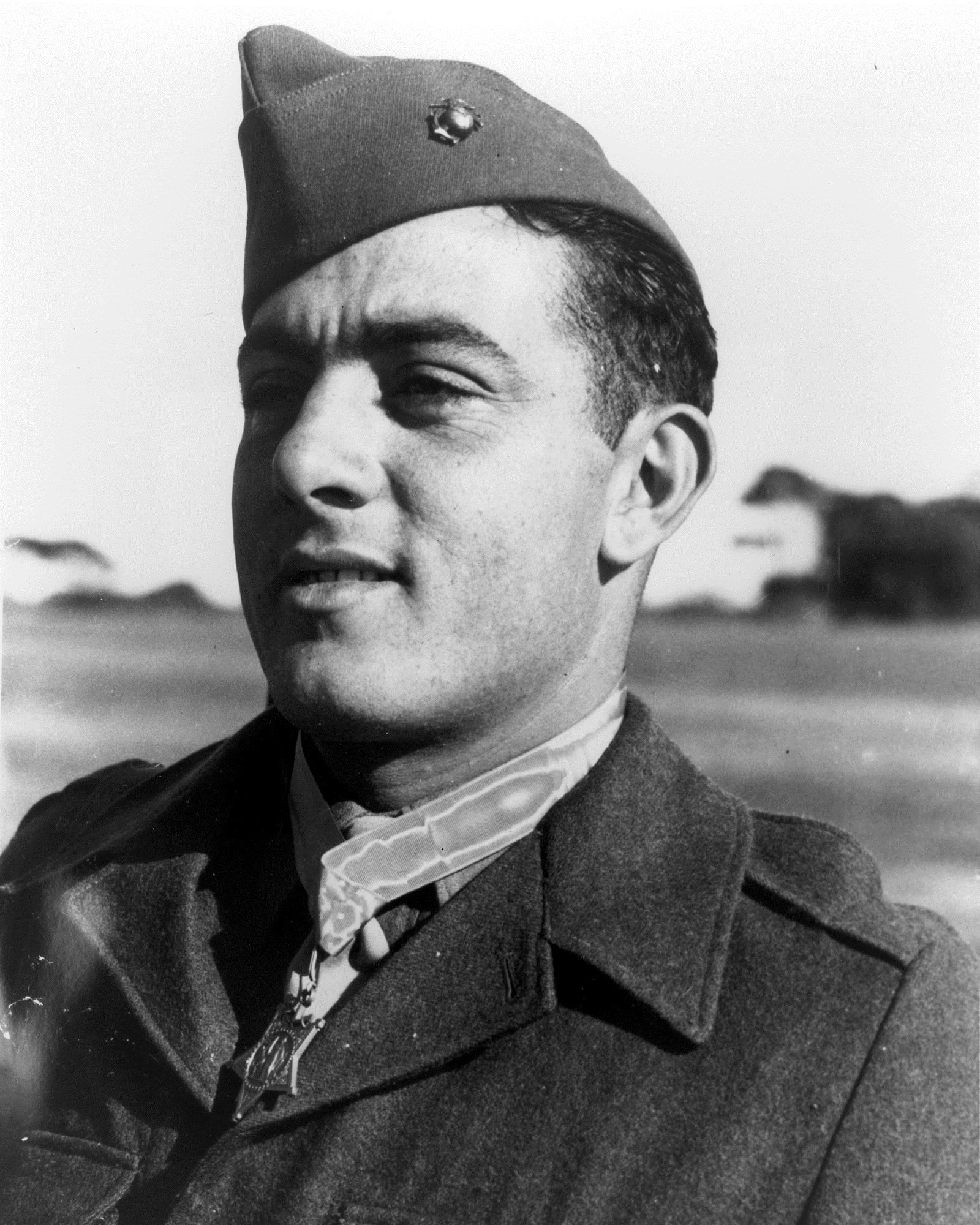

Gunnery Sgt. John Basilone was born to be a United States Marine.

Ask any past or present Marine about the legendary New Jersey native and they’ll be able to rattle off facts in the same history-cherishing fashion of other Marine Corps demigods — the Dan Dalys, the Smedley Butlers, the Chesty Pullers and Carlos Hathcocks — who are hammered home into the brain housing group from the moment a recruit steps on the yellow footprints.

Basilone served three years in the Army during the 1930s, but it wouldn't be until he enlisted in the Marine Corps — and the country’s subsequent plunge into World War II — that he would reach mythical standing.

On the night of Oct. 24, 1942, in the jungles of Guadalcanal, one of the hundreds of islands that comprise the Solomons, then-Sgt. Basilone was commanding two heavy .30-caliber machine gun sections from First Battalion, Seventh Marines, that were tasked with holding a narrow pass at the Tenaru River.

As the small crews of Marines dug in for the night, a Japanese regiment numbering 3,000 men attacked the line, hammering the Marines with grenades and mortar fire. Wave after wave were kept at bay by the small teams of Marines, until one of the gun crews was disabled by enemy fire.

With total disregard for his own life, Basilone carried about 90 pounds of weaponry and ammunition to the silenced gun pit, running a distance of 200 yards through enemy fire and encountering Japanese soldiers along the route, who he killed with his Colt .45 pistol.

Basilone continued running back and forth between gun pits, supplying ammunition to those desperately in need and clearing gun jams for his junior Marines.

Amidst the carnage, Basilone lost his asbestos gloves, hand protection critical for holding or swapping out the scalding hot barrels of the heavily used machine guns.

During the height of the battle, Basilone barehanded the searing barrel of his machine gun without hesitation and continued putting rounds downrange, killing an entire wave of Japanese soldiers and burning his hands and arms in the process.

Enemy bodies were (literally) piling up so rapidly that he — or other Marines, depending on the story — had to vacate their defensive positions to knock over the growing wall of flesh so they could reestablish clear fields of fire.

An entire Japanese regiment was thwarted by the gun crews, and by the time reinforcements arrived, only Basilone and two other Marines were left standing. Basilone used his crews’ machine guns, his pistol and a machete to kill at least 38 enemy soldiers by himself.

Pfc. Nash W. Phillips was with Basilone on Guadalcanal and recounted the other-worldly efforts of his sergeant.

“Basilone had a machine gun on the go for three days and nights without sleep, rest or food,” said Phillips, who lost a hand in the fight.

While receiving medical treatment, Phillips recalled Basilone’s mythical appearance as he came to to check on him.

“He was barefooted and his eyes were red as fire,” he said. “His face was dirty black from gunfire and lack of sleep. His shirt sleeves were rolled up to his shoulders. He had a .45 tucked into the waistband of his trousers. He'd just dropped by to see how I was making out; me and the others in the section. I’ll never forget him. He’ll never be dead in my mind!”

Basilone would go on to be awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for his actions on Guadalcanal. He returned to the U.S. to assist the war bond effort — and was offered a commission and the chance to spend the rest of the war in Washington.

He turned the offer down, forgoing the public attention being a war hero yielded and opting instead to return to combat.

On February 19, 1945, Basilone stormed Red Beach on Iwo Jima. Pinned down by enemy machine gun fire, he led his gunners up the steep black sand, kicking his inexperienced Marines to get off the beach as they hugged the ground for cover.

Minutes after destroying a Japanese blockhouse, Basilone and four members of his platoon were killed when an enemy artillery shell exploded. He was 28 years old.

Gunnery Sgt. Basilone would be posthumously awarded the the Purple Heart and the Navy Cross for his actions on Iwo.

Read his entire Medal of Honor citation here.

RELATED

J.D. Simkins is the executive editor of Military Times and Defense News, and a Marine Corps veteran of the Iraq War.