Lawrence Brooks, the United States’ oldest living World War II veteran, died Wednesday morning, according to his daughter and caregiver, Vanessa Brooks.

The supercentenarian’s health was winding down, Vanessa Brooks confirmed to Military Times, and he was in and out of the local veterans’ hospital several times in recent months ― but he was still alert, enjoying the holidays and watching his beloved Saints play until the end.

Brooks, a local celebrity in New Orleans, celebrated his birthdays with parties thrown by the nearby National World War II Museum.

He had received numerous gifts and more than 10,000 birthday cards throughout the years in recognition of his service during the war.

For his 112th birthday in September 2021, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the celebration was brought to his house in the form of a drive-by party.

Brooks had danced on his porch, serenaded by the museum’s singing trio, the Victory Belles, while a military flyover banked down his Central City New Orleans shotgun house.

The Black Army veteran served at a time of segregation in U.S. history, where white and Black soldiers slept in separate tents and ate separately. But he insisted that in the military he never dealt with any problems of race, and stories from the war were told with positivity and laughter.

He died as he had planned ― in his own bed in his home in New Orleans.

The son of sharecroppers

The son of sharecroppers, Brooks was one of fifteen children.

He was born in 1909 just north of Baton Rouge in Norwood, Louisiana, and was raised just outside of Stephenson, Mississippi, a small sawmill town where his family moved for work during the Depression.

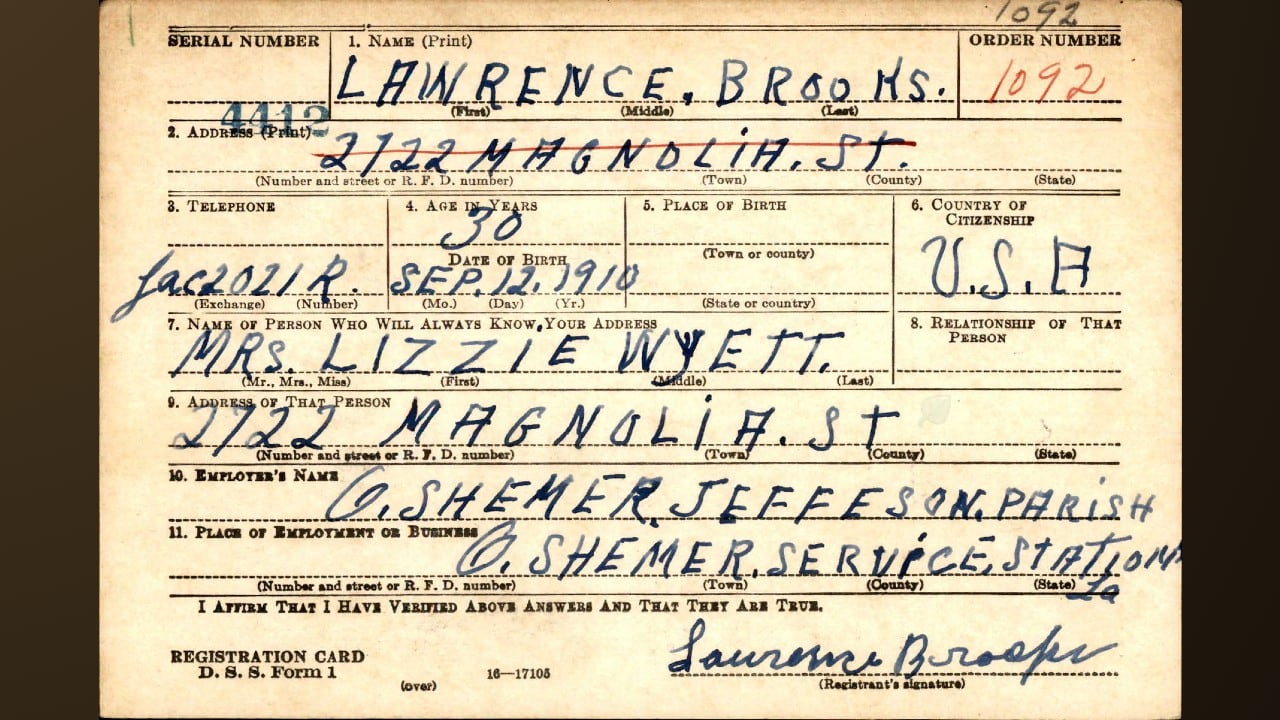

The supercentenarian was drafted and entered the Army in 1940, serving in both Louisiana and Texas. He participated in the famed Louisiana Maneuvers, where 400,000 soldiers converged on the state for readiness exercises in response to Germany’s invasion of Poland and France.

Brooks completed his obligatory one-year service, he previously told Military Times, was discharged and back at work in New Orleans in November 1941. A few weeks later, after the attack on Pearl Harbor, he returned to the Army.

“There was no question,” Brooks told the National World War II Museum in one of his many oral history interviews. “They just came right back and got me again.”

He said he was sent by train at Camp Shelby in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, where he joined the 91st Engineer Battalion, a unit comprised of 1,193 Black enlisted soldiers and 25 white officers. He says that he journeyed to Pennsylvania for vaccines and additional training before traveling to the South Pacific theater.

“Indiantown Gap is where I got my inoculations before we left,” Brooks said in an interview with Military Times in late 2021.

In March 1942, Brooks found himself in New York Harbor heading to war aboard a “huge” converted ocean liner. He said he sailed on the Queen Mary, the troop carrier dubbed the “Grey Ghost” due to her agility and speed in outrunning the enemy.

He recounted that the voyage lasted close to a month amid a zig-zag course dodging submarines. His destination was Queensland, Australia, a key defensive area in the war against Japan.

Brooks said his unit arrived in Brisbane, Australia, in early April and ended its journey in Townsville, Australia.

The private first class loved to reminisce about the Australian people’s acceptance of the 9,000 Black soldiers that served there and the lack of Jim Crow laws that he experienced.

“They were nice people, the Australians,” said Brooks recently. “They were wonderful.”

Freedom in Australia

Brooks traveled to Brisbane, Australia, through numerous small coastal towns and islands, and spoke with wonder at the lack of segregation in the places he visited.

He talked about his close relationship with a white woman and her family in Townsville, Australia.

“I had a lady friend there; she had a hotel and a bar,” said Brooks. “I used to go to her father’s place (house) and helped deliver liquor to their hotel.”

Brooks said he attended Townsville’s dance halls, hotels and cinemas and mixed freely with the population. This was a freedom unheard of in the southern United States at the time.

Brooks, like most in his battalion, didn’t see combat.

Instead, he was a driver, valet and cook for three officers, two lieutenants and a captain. He no longer remembered their names; only that one was from New York.

He told of chauffeuring his officers around Queensland, Australia, and to the officers’ club in Townsville, Australia, in his weapons carrier, or as he fondly referred to it, “my big ole Army car.”

The numerous war offices were located in town, 40 minutes north of the unit’s various camps, he said. Because of his “batman” position, he had the unusual freedom to explore the area while his commanding officers were in town.

When asked about any racial issues with his officers, he says none occurred.

Only recently, he was gazing at newspaper archives of some of his officers and laughing as he recounted what he termed as “shenanigans.” Brooks spent that day looking at photographs of his old unit, their jazz band, USO parties and his favorite haunts in Townsville, Australia.

“My officers were good to me,” said Brooks. “I never had any problems.”

He cooked their meals at the joint mess hall and delivered them back to camp. The white officers ate separately from the black soldiers.

“We had our tents, and the whites had their tents,” said Brooks. “They were next to each other, like next door.”

The engineer unit built numerous frame buildings, Quonset huts, roads, hospitals, housing, shops and recreation centers. Brooks told of working on Horn Island, Papua-New Guinea and the Philippines.

“We built bridges, roads, and airstrips,” said Brooks in a previous oral history interview describing his unit. “That was our job.”

He remembered digging and diving into foxholes on numerous occasions when the Japanese strafed his unit near Townsville, Australia, and New Guinea. One of his favorite anecdotes was about Thursday Island.

“We was on Horns Island, and the Japanese would come and drop bombs on us,” said Brooks. “They had a body of water about the size of the lake (Lake Pontchartrain) between Thursday Island and us.”

Brooks said his unit rowed small boats over to the island just after nightfall to avoid the air raids. His story was that the enemy wouldn’t strafe or bomb the island because it was the location of a sacred Japanese graveyard.

“We was sneaking over there at night,” said Brooks, who couldn’t stop laughing as he told the story. “We rowed pretty fast. They didn’t shoot us … because they couldn’t see us.”

A favorite anecdote occurred while Brooks was island hopping between Australian territories in a C-47. He said they lost an engine and were flying low.

The navigator walked back into the fuselage and started dumping bales of barbed wire to lighten the load. Brooks said that he got up and headed to the cockpit before being told to stop.

“My sergeant wanted to know where I was going,” Brooks had said, always giggling whenever he retold the response he gave his superior. “I said, the only two parachutes on this plane are up there. If they jump out, I’m grabbing onto one of them.”

Brooks said his unit left the South Pacific in 1944 and eventually separated from service in 1945.

‘A good soldier’

Most of his stories rang with laugher.

One would get the impression that there was still much to tell, but Brooks decided long ago to focus only on the positive. If he experienced bad times in the military, he was not inclined to share them.

When asked in late 2021 what he would like his legacy to be, if anything, his thoughts returned to the war.

“I would like to be remembered as a strong man,” said Brooks, “A good soldier.

Brooks had recently requested a new U.S. Army uniform to replace the original he’d lost sixteen years ago in Hurricane Katrina.

He was presented with an authentic reproduction World War II uniform and his old unit’s badge during a recent short stay in the New Orleans VA hospital at the beginning of November.

Brooks had immediately recognized the components of the summer service uniform he wore while serving in the Pacific Theater.

Not long after, he was back home at his house in New Orleans, posing in his “khakis.”

He had smiled, turned his new garrison cap over and over in his hands before placing it on his head, then had inspected his unit insignia and badge, the 91st Engineer Battalion.

The unit’s current commanding officer had recently sent him replacement medals and a certificate of appreciation for his service. But, unfortunately, his good conduct medal is still lost, and his daughter was trying to find him a replacement.

His daughter recently gave several interviews lamenting how Black World War II veterans, including her father, were denied GI Bill benefits. She says he often spoke of how much he wanted to go to school after the war.

“My father earned the Good Conduct Medal, Meritorious Service Medal, and Presidential Unit Medal, then he was left behind,” said Vanessa Brooks. “He served the same five years. He was bombed and strafed in the South Pacific but was not offered a low-interest bank loan, a reduced down payment for a house, or an education.”

She says she plans to bury her father wearing his new uniform, as he requested.

Kristine Froeba is a freelance writer based in New Orleans. She was involved in helping locate and raise funds for Lawrence Brooks’ new uniform.