SAN DIEGO (AP) — Since President Joe Biden asked the Pentagon last week to look at adding the COVID-19 vaccine to the military’s mandatory shots, former Army lawyer Greg T. Rinckey has fielded a deluge of calls.

His firm, Tully Rinckey, has heard from hundreds of soldiers, Marines and sailors wanting to know their rights and whether they could take any legal action if ordered to get inoculated for the coronavirus.

“A lot of U.S. troops have reached out to us saying, ‘I don’t want a vaccine that’s untested, I’m not sure it’s safe, and I don’t trust the government’s vaccine. What are my rights?’” Rinckey said.

Generally, their rights are limited since vaccines are widely seen as essential for the military to carry out its missions, given that service members often eat, sleep and work in close quarters.

Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin has said he is working expeditiously to make the COVID-19 vaccine mandatory for military personnel and is expected to ask Biden to waive a federal law that requires individuals be given a choice if the vaccine is not fully licensed. Biden has also directed that all federal workers be vaccinated or face frequent testing and travel restrictions.

RELATED

Lawyers say the waiver will put the military on firmer legal ground so it can avoid the court battles it faced when it mandated the anthrax vaccine for troops in the 1990s when it was not fully approved by the federal Food and Drug administration.

The distrust among some service members is not only a reflection of the broader public’s feelings about the COVID-19 vaccines, which were quickly authorized for emergency use, but stems in part from the anthrax program’s troubles.

Scores of troops refused to take that vaccine. Some left the service. Others were disciplined. Some were court martialed and kicked out of the military with other-than-honorable discharges.

In 2003, a federal judge agreed with service members who filed a lawsuit asserting the military could not administer a vaccine that had not been fully licensed without their consent, and stopped the program.

The Pentagon started it back up in 2004 after the FDA issued an approval, but the judge stopped it again after ruling the FDA had not followed procedures.

Eventually the FDA issued proper approvals for the vaccine, and the program was reinstated on a limited basis for troops in high-risk locations.

Military experts say the legal battles over the anthrax vaccine could be why the Biden administration has been treading cautiously. Until now, the government has relied on encouraging troops rather than mandating the shots. Yet coronavirus cases in the military, like elsewhere, have been rising with the more contagious delta variant.

RELATED

If the military makes the vaccine mandatory, most service members will have to get the shots unless they can argue to be among the few given an exemption for religious, health or other reasons.

According to the Pentagon, more than 1 million service members are fully vaccinated, and more than 237,000 have gotten at least one shot. There are roughly 2 million active-duty, Guard and Reserve troops.

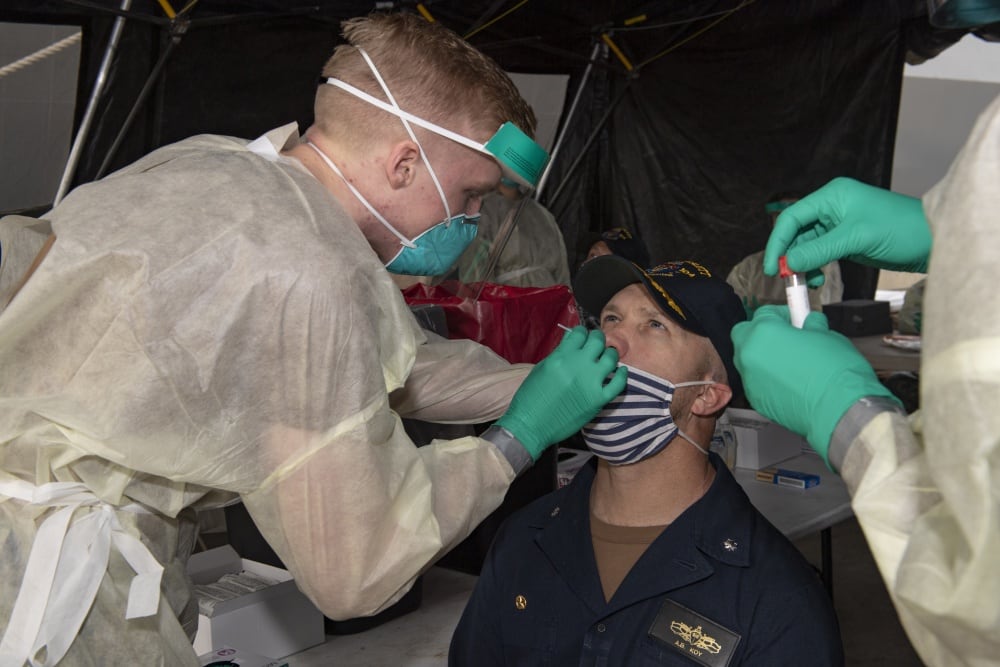

Many see the COVID-19 vaccine as being necessary to avoid another major outbreak like the one last year that sidelined the aircraft carrier Theodore Roosevelt and resulted in more than 1,000 crewmember cases and one death.

An active-duty Army officer said he would welcome the vaccine among the military’s mandatory shots. The soldier, who asked not to be named because he was not authorized to speak to the media, said he worries unvaccinated service members may be abusing the honor system and going to work without a mask.

He recently rode in a car with others for work but didn’t feel like he could ask if everyone was vaccinated because it’s become such a political topic. Commanders have struggled to separate vaccinated and unvaccinated recruits during early portions of basic training across the services to prevent infections.

Accommodating unvaccinated troops would burden service members who are vaccinated since it would limit who is selected for deployment, according to active-duty troops and veterans.

“The military travels to vulnerable populations all over the world to be able to best serve the U.S.,” said former Air Force Staff Sgt. Tes Sabine, who works as a radiology technician in an emergency room in New York state. “We have to have healthy people in the military to carry out missions, and if the COVID-19 vaccine achieves that, that’s a very positive thing.”

Dr. Shannon Stacy, who works at a hospital in a Los Angeles suburb, agreed.

“As an emergency medicine physician and former flight surgeon for a Marine heavy helicopter squadron, I can attest that COVID-19 has the potential to take a fully trained unit from mission ready to non-deployable status in a matter of days,” she said.

The biggest challenge will be scheduling the shots around trainings, said Stacy, who left the Navy in 2011 and did pre-deployment, group immunizations.

Arnold Strong, who retired from the Army as a colonel in 2017, said he believes it’s not anything the U.S. military cannot overcome: Troops working in the farthest corners of the Earth have access to medical officers. Given that most people sign up to follow orders, he thinks this time will be no different.

“I think the majority of service members are going to line up and get vaccinated as soon as it is a Department of Defense policy,” he said.

Strong has lost five friends to the virus, three of whom were veterans.

His hope is that the military can set the example for others to follow.

“I would hope if people see the military step up and say, ‘Yes, let’s get shots in arms,’ it will set a standard for the rest of country,” he said. “But I don’t know because I think we face such a strong threat of disinformation being deployed daily.”

Associated Press writer Lolita C. Baldor in Washington contributed to this report.