Capt. Justin Tahilramani chuckled at the irony of it all.

He’s an active duty Army Acquisition Corps officer, stationed at Fort Benning, Georgia. Tahilramani specializes in awarding and administering complex government contracts — he oversaw $266 million in Army contracts in the past few years and earned the government’s trust to negotiate up to $250 million in new ones.

But his military career is likely ending due to a few thousand dollars, he explained to Army Times in a series of phone interviews. He is long-term collateral damage of one of the most ill-constructed contracts in the service’s history.

Tahilramani lost his promotion to major — and will likely be pushed out of the active duty Army altogether — over one of three $2,000 referral payments he received for inspiring fellow Texas Tech cadets to join the Texas National Guard in 2006.

“There’s not a whole lot more ironic than that,” he quipped.

Tahilramani and an unknown number of other soldiers have had their lives upended by the long-term consequences of a massive investigation into claims of widespread fraud in the Guard Recruiting Assistance Program. The probe did not result in criminal charges for him or many others. Of the tens of thousands of G-RAP payments that were investigated, the New York Times reported only about 150 people had been charged with a crime as of 2017.

According to a Senate Armed Services Committee background memo prepared in 2014, the G-RAP program, which was in effect from 2005 to 2012, fed hundreds of millions of dollars to a private company, Docupak, which employed more than 100,000 Guard members like Tahilramani as civilian independent contractor “recruiting assistants,” or RAs.

They would receive $2,000 for each enlisted Guard member they referred, and it worked. Roughly 130,000 troops joined from G-RAP referrals over the seven-year period.

Army officials later admitted to Congress that the entire program may have violated federal contracting laws.

The director of the Army National Guard, who oversaw the contract, now-retired Lt. Gen Clyde Vaughn, ultimately received a reprimand faulting him for a lack of oversight of the program. The National Guard Bureau officer who arranged the contract also left the Guard to work for Docupak.

The Army’s Criminal Investigation Division, which stood up a special task force to investigate the G-RAP payments, claimed Tahilramani was among the soldiers who pocketed undeserved payouts after lying about referring recruits to the Army.

But critics of CID’s tactics argue that their methods — cold calling recruited troops several years after they’d joined, and asking them if they remembered the RA who referred them — were rushed, inexact and sometimes contradicted reality.

Tahilramani’s referrals came after his professor of military science authorized him to give a presentation to younger cadets on the benefits of joining the Guard while in ROTC, he explained. A handful enlisted after his briefing, and he collected their information from the local recruiter for input into the G-RAP system in accordance with program rules.

In 2014, the federal government declined to prosecute Tahilramani, saying that the statute of limitations had passed. That same year, Justice Department officials declined to prosecute Tahilramani.

A federal prosecutor said in an email to CID, which was obtained by Army Times, that the statute of limitations had passed, the alleged fraudulent payments were negligible and the evidence of wrongdoing was thin.

But it was still enough for CID to “title” Tahilramani, creating a permanent record that he had been subject to a criminal investigation. Some veterans have found that the titling process saw them entered into an FBI criminal database that is regularly used for background checks.

It’s not clear how many service members out of the thousands involved with G-RAP were titled, though. In a February 2014 progress report CID made to Congress, at least 110 officers — including a major general — and an unknown number of enlisted troops were titled. The CID investigations didn’t conclude for years afterwards. According to an article in The Criminal Law Practitioner, more than 3,200 Guard troops faced criminal investigation.

When Tahilramani became a contracting officer, he had an 18-month vetting period where officials assessed his trustworthiness. They considered his alleged misconduct and dismissed it. He was later selected for promotion to major.

“It was vindicating to know that they saw past it,” he explained. “They saw me for what I brought to the table.”

Then the old allegations came back without warning, stopping his promotion in its tracks because of the “adverse information” in his file. A promotion review board ultimately put him back on the list, but the Senate did not confirm his promotion before his eligibility expired.

He’s up for promotion again this fiscal year, but he’s had enough. And new officer promotion rules mean that the board can see the CID report while deciding whether to promote him, “basically killing any chance for selection,” he said.

“I would love to keep fighting,” Tahilramani said. “I just don’t have it in me anymore. The Army ruined my life and career over a $2,000 G-RAP payment.”

“Nobody’s willing to do anything about it to help anybody,” he said in frustration.

But that could be changing, as CID has reopened the investigation of another similarly situated officer, Capt. Gilberto De Leon, amid pressure from Congress.

CID spokesperson Pat Barnes confirmed to Army Times in an email that the agency “has re-opened the investigation pertaining to CPT De Leon. We cannot provide any further details at this time.”

New hope for some

The door could be open for others, as well.

“Army CID will consider re-opening any G-RAP cases when the alleged subject presents new and relevant information that was not considered during the original investigation,” Barnes said. “Any individual who believes inaccurate information was submitted to NCIC may submit an amendment request to usarmy.belvoir.usacidc.mbx.crcfoiapa@army.mil.”

The past month has been a rollercoaster for De Leon, an armor officer and security forces advisor who is assigned to Fort Carson, Colorado. He was titled by CID due to concerns over approximately $11,000 he earned from referring six troops while a member of the Kentucky National Guard — but he was never charged with a crime.

On March 15, he published a Military Times op-ed detailing his ordeal. He also fired off a letter to CID’s new civilian director, Gregory Ford.

RELATED

De Leon was initially selected for promotion to major in 2019, but during the post-selection review, his promotion screeched to a halt due to “adverse information” in his file — the long-closed G-RAP investigation.

A promotion review board said De Leon should still be promoted — but administrative delays kept him from getting the promotion he’d earned.

After De Leon wrote his op-ed in Military Times, six members of the House of Representatives penned a letter March 28 requesting “immediate intervention” from senior military leaders, including Army Secretary Christine Wormuth and Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin. But it was too late.

On April 13, Army Secretary Christine Wormuth formally notified De Leon, a father of six, that his promotion eligibility had expired.

Although De Leon is on his way out of the Army, angling for a new career as a regenerative farmer, he isn’t going quietly. “I realized there’s so many people affected with this,” he said of why he kept going despite depression and other struggles.

CID’s assistant director of investigations told De Leon via email on April 16 that his staff had “look[ed] into the concerns you expressed [to Ford] regarding the criminal investigation into your involvement with G-RAP.”

As a result, the CID official said, “I have directed your investigation be reopened to ensure that the investigation is complete and inclusive of all available evidence.”

De Leon told Army Times in a series of phone interviews that CID “never even interviewed” him during the original case.

“I think [CID reopening the case] could be a good thing…maybe since it’s reopened, they can remove the title,” he said.

The armor officer also hopes the agency’s reconsideration “can help shine light for other victims” of the investigation.

A ‘failure of military justice’

Tahilramani, the contracting officer, is more skeptical that the same organization that investigated him can fairly review any of the G-RAP cases — he wants to see an “independent” review, and he thinks all titled people should have their cases reconsidered.

Jeffrey Addicott, a law professor and director of the Warrior Defense Project at St. Mary’s University School of Law, agrees with Tahilramani’s take. He thinks De Leon’s case was only reopened because of inquiries from members of Congress.

Addicott described CID as “incompetent” in one of several phone interviews. He is also skeptical that the agency will actually review other past cases, as CID spokesperson Barnes indicated they would.

“I’ve submitted to CID on numerous occasions all sorts of legal memos pointing out how…[the G-RAP investigation] is totally flawed,” he explained.

Addicott, a retired lieutenant colonel, has been working to help G-RAP investigation targets clear their names for years. Now, De Leon is one of his clients. Addicott wrote a law review article in 2020 about how, in his words, the “G-RAP fiasco…destroyed” hundreds of “innocent” troops’ lives.

The former JAG officer explained how the massive investigation, which included more than 200 active and reserve CID agents under the banner of Task Force Raptor, was born in response to a 2012 audit that warned there could be as much as $92 million in fraud associated with G-RAP and similar programs for the Army’s other components.

While there were some cases of out-and-out fraud, such as kickback rings among Texas recruiters, the investigations never yielded close to the purported $92 million.

By February 2014, when a Senate panel held a hearing on G-RAP, it was apparent that the service would never recover most of the alleged losses.

Lawmakers, including then-Sen. Claire McCaskill, pressured the Army to find more fraud, and to punish it.

“It is going to break my heart if there are a lot of people who are going to get away with this,” said McCaskill. “We have to figure out a way to hold every single one of them accountable.”

Meanwhile, according to written testimony from Army officials in 2014, federal prosecutors around the country were refusing to pursue cases where CID believed a crime occurred. Some of those refusals were due to factors like the five-year statute of limitations for federal fraud cases or limited prosecutorial resources, but Addicott’s law review article raised questions about the quality of the investigations delivered to prosecutors.

He used the case of Lt. Col. John Suprynowicz — who declined to speak on the record for this story, instead pointing to the law review article — as an example.

In 2016, Suprynowicz, a veteran of the 1993 Battle of Mogadishu, had his security clearance pulled and his pending promotion to lieutenant colonel halted. CID had informed Suprynowicz’s then-commander that they believed he had received bonuses for 18 recruits he never actually met.

The CID file, described as “two inches thick” by Addicott, included sworn statements from agents summarizing phone calls with the referred recruits.

There was just one problem: Suprynowicz had met with all of them, and a command investigation ultimately determined that all 18 had discussed joining the Guard with the officer. When he was accused of improperly handling personally identifying information for the recruits, Suprynowicz showed that he had followed program rules in obtaining it from local recruiters.

Investigations of this caliber didn’t come cheap, either. A 2016 episode of 60 Minutes revealed that the Army had spent “nearly $28 million” on Task Force Raptor.

As the New York Times reported in 2017, the service later admitted that Task Force Raptor only identified $6 million in alleged fraud, of which just $3 million was recovered — a far cry from the $92 million in fraud the Army warned could be out there.

Even then-Army Secretary Mark Esper acknowledged the issues in 2019 when he signed a promotion recommendation memorandum for an officer titled by Task Force Raptor. The memo, prepared by an action officer, condemned G-RAP’s “unclear guidance” and said that “the circumstances surrounding G-RAP are too unclear to prove known malice and blame on any one participant.”

John Goheen, a National Guard Association of the U.S. spokesperson, told Army Times that “the Army’s quest to find $100 million in fraud [was] overbearing.” He described the investigations as “troubling.”

Asked about De Leon’s reopened investigation, Goheen noted, “there’s some other officers and NCOs that would love to have their cases reopened. And quite possibly rightfully so…not everybody’s innocent here, but certainly some innocent people have lost careers.”

The fallout goes beyond military careers, too.

Branded as criminals — with long-term consequences

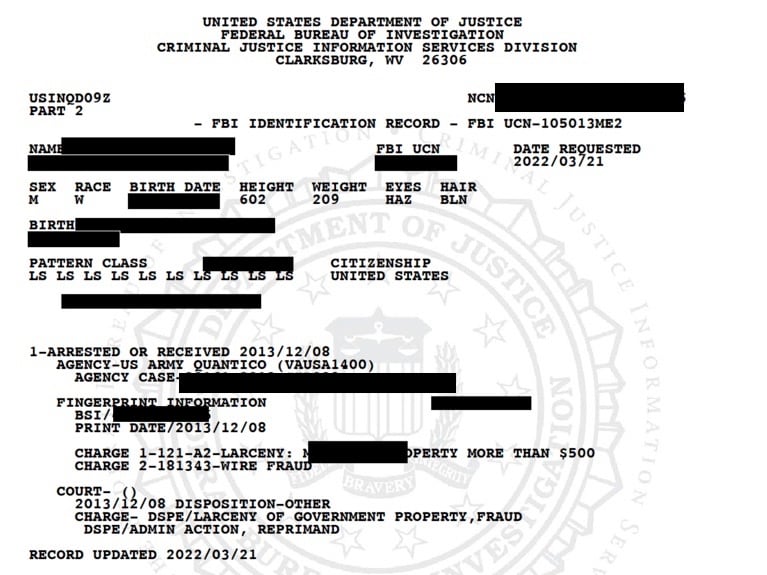

Many of the investigation’s targets have since found that they were “titled” by CID. Because the agency determined there was “probable cause” they’d committed a crime, they’ve been entered into the FBI’s National Crime Information Center database.

NCIC is one of the primary databases used by state and local governments for criminal background checks, although private background check companies cannot access it.

Doug O’Connell, a retired Special Forces colonel who heads a law firm in Austin, Texas, has represented dozens of troops facing punishment for their G-RAP participation. He told Army Times in a phone interview that “everyone who was titled for G-RAP [may] have a criminal history showing that they were arrested” — even if they weren’t.

Probable cause is one of the lowest legal standards, especially in military settings, explained Addicott and O’Connell. It only requires that a prosecutor agree with CID officials that they have reason to believe someone may have committed a crime. Their decision doesn’t represent a commitment to take it to trial, though.

There’s barely any record of the probable cause determination and the reasons behind it in some cases, too, because attorneys could provide their opinion via phone. And the people deciding whether there’s probable cause in military justice cases are the very prosecutors who may try the case at a later point.

“Probable cause determinations are made by the appropriate independent legal authority, whether that is an Army trial counsel, a local state or district attorney, or a Federal Assistant U.S. Attorney,” said Barnes, the CID spokesperson. “The probable cause opinions may be oral or in writing, depending on local procedures of the legal authority.”

O’Connell took issue with Barnes’ assertion that prosecutors are “independent” legal authorities. He pointed out that in all civilian courts, “the 4th Amendment and the federal rules of criminal procedure require that…[a judge] makes the decision on whether probable cause exists” rather than a junior prosecutor.

Addicott called the practice “rubber-stamping.”

Once a prosecutor has agreed with CID that they believe a crime occurred, they can then enter the allegations into NCIC, according to Defense Department regulations. But why do they appear as arrests?

The problem lies in how the NCIC database displays records — and how the military justice system reports into it, the lawyers said. All entries begin with a date someone was “arrested or received.”

“The NCIC system is designed to record when people get arrested and then the disposition of the case — convicted, acquitted [or] dismissed,” said O’Connell.

But administrative punishments like titling and reprimands meted out by the Army in most G-RAP cases “are worse than showing that they’re convicted, because the way it looks in [NCIC, it appears] the case is still pending without a disposition,” O’Connell added.

Addicott has dealt with several G-RAP cases where government agencies thought his clients had been arrested and convicted for the offenses listed in their NCIC records.

According to Addicott’s law review article, a Guard member who worked as a civilian police officer at a university in South Carolina lost his job because CID had submitted records to NCIC that said he’d been arrested over G-RAP fraud when he hadn’t.

The law professor described another situation in which a New York Guard client nearly was fired from his career as a prison guard after his past trouble with G-RAP surfaced. Addicott flew to New York to make an ultimately successful appeal for the corrections officer to keep his job.

Sgt. Kristin Steakley of the Tennessee Guard was never arrested or charged with a crime by G-RAP investigators, either. But her NCIC record says CID “arrested or received” her on Oct. 19, 2012, in Quantico, Virginia, she told Army Times in an email.

Steakley thought the stress of the investigation was behind her, until she went to renew her Tennessee concealed carry permit in 2014, she said. State officials sent the military police soldier a letter saying that because she “had been arrested,” she couldn’t renew her permit, which she needed for her civilian job as an armed security guard.

She lost her job, and her dreams of landing a career in law enforcement dissipated.

Steakley said she had to seek psychiatric care after she “lost everything” and her roommate found her “with a gun to my head.” Since then, she has managed to successfully renew her security clearance and find work within the Army Reserve, but the scars are still there.

Addicott finds it encouraging that CID is reopening De Leon’s case, but he thinks the volume of people affected by potentially defective investigations necessitates more drastic action. He proposed legislation before that would reform the titling system, which he described as “a stab in the back” as currently constructed.

“The only way to get that change is to have Congress change it,” Addicott said.

Congress has scrutinized the process in the past, including in 2001, when the annual defense policy bill ordered the DoD to formally review its titling practices.

The resulting 2002 DoD inspector general report inspired some changes to the system.

O’Connell hopes to see CID’s new civilian leadership take action to proactively review the G-RAP cases, but he’s worried that “military law enforcement people feel as if they have unchecked power…[and] they’re getting away with [the NCIC entries] because of bureaucratic arrogance, and dysfunctional Army leadership.”

Tahilramani, the contracting officer, thinks an “independent review” of the G-RAP cases may be the best way forward, and the best way to rebalance the scales of justice.

He’s frustrated, though, at how he thought the issue was behind him.

“If the Army wanted to deal with this, they should have dealt with it 10 years ago,” he said. “Don’t let somebody have a successful career for eight, 10 years and then drag up sometime from [15 years] ago and ruin them…Is the promotion system really the right time and the right avenue to do that?”

Davis Winkie covers the Army for Military Times. He studied history at Vanderbilt and UNC-Chapel Hill, and served five years in the Army Guard. His investigations earned the Society of Professional Journalists' 2023 Sunshine Award and consecutive Military Reporters and Editors honors, among others. Davis was also a 2022 Livingston Awards finalist.