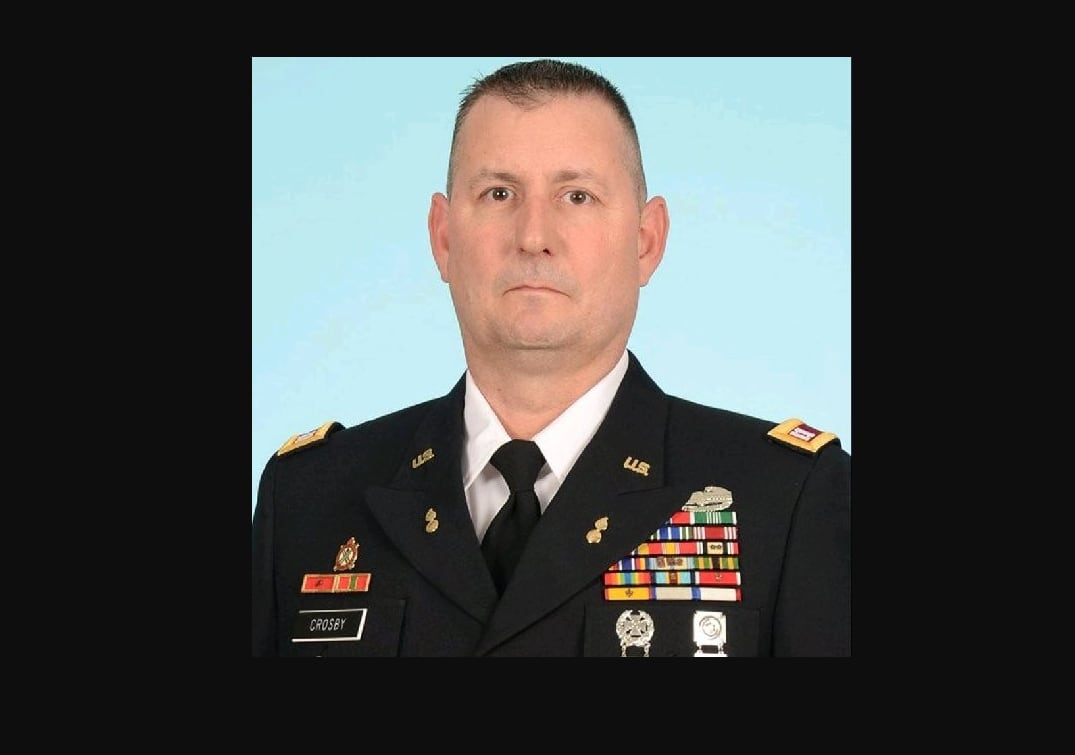

Capt. Billy Joe Crosby pleaded guilty to simple assault. But he was initially accused of “motorboating” a subordinate during a May 2021 promotion ceremony that she’d begged not to have because he’d announced his intent to place her new rank on her chest using his teeth.

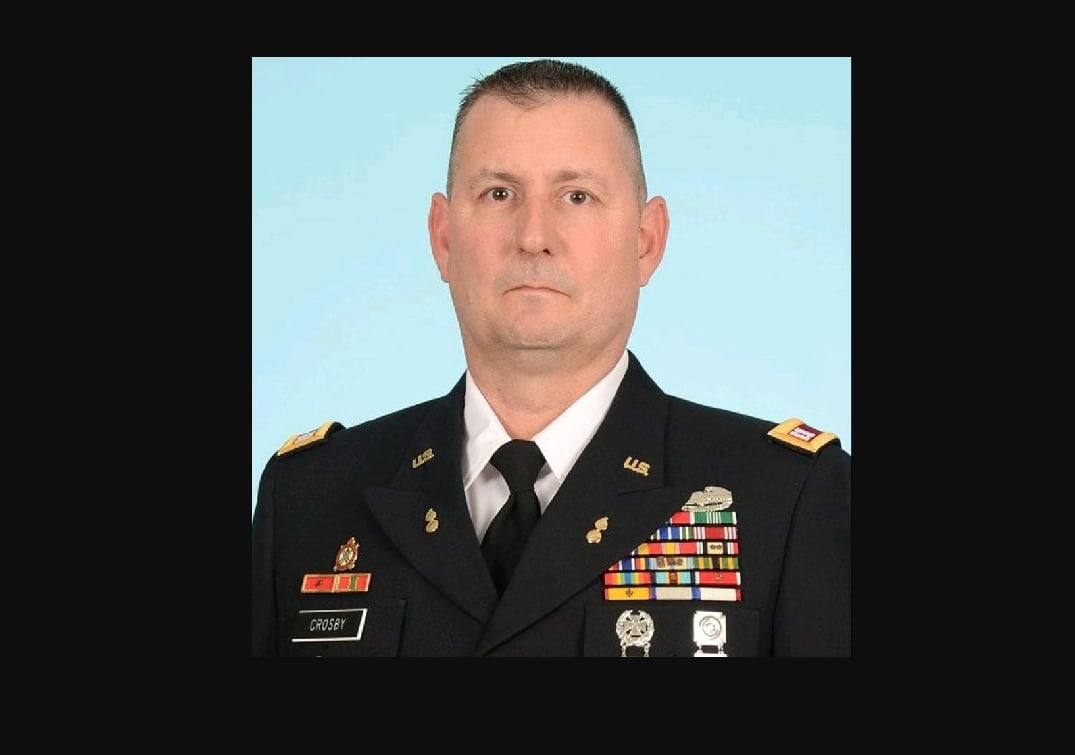

A former command sergeant major, now-Sgt. 1st Class Clinton Murray, pleaded guilty to assault. That came after he was hauled back to the Army via deserter warrant in August 2020 after allegedly forging his clearing paperwork to retire and avoid his second sexual assault court-martial.

Court records reveal the two cases have a common thread that troubles victims, attorneys and advocates alike: each of the accused received a favorable plea deal from the Army allowing them to retire, and neither were convicted of a crime that would require sex offender registration in virtually any state. Though the victims agreed to the plea deals with varying reluctance, they believe the Army left them without a choice.

Crosby pleaded guilty at a Nov. 10 general court-martial to touching the soldier’s breast and conduct unbecoming an officer — but the touching was only a simple assault, rather than the abusive sexual contact charge he’d initially faced. A judge sentenced Crosby to 30 days in jail, but his plea deal prevented the judge from kicking him out and taking his retirement.

RELATED

Murray, who was previously acquitted of sexually assaulting a junior soldier in Afghanistan after an officer helped him destroy evidence, was later accused of blackmailing the same officer for nude photos. He was also accused of attempting to share nude photos of her, coercing her into sex and directing her to destroy evidence ahead of the first trial, among other charges related to his alleged desertion.

But under his plea deal, Murray was not convicted of a sexual offense or a felony equivalent — nor was the judge allowed to sentence him to a punitive discharge. According to trial records, he instead pleaded guilty June 15 to assault for grabbing the officer’s arm in his bedroom on the date of the alleged sexual assault. He also pleaded guilty to adultery, fraternization, failure to properly route his clearing worksheet and sexual harassment, for which he is currently serving a 90-day sentence.

Both either have or will retire with their military pensions. A Louisiana National Guard spokesperson confirmed that Crosby retired March 31. And Murray will retire as a sergeant first class after the judge reduced him in rank, according to a source familiar with the court proceedings.

Victims from the Murray and Crosby cases told Army Times of their frustration with the culture in the units where they experienced the crimes, as well as what they perceived as failures in the military justice system that allowed perpetrators to walk away with pensions intact thanks to favorable plea deals.

The structure of the military justice system encourages deals such as these and it will be years before any changes materialize — if any do at all — after the service’s Office of Special Trial Counsel takes over prosecutions for sexual misconduct and other major crimes by late December 2023, according to military law experts who also spoke with Army Times.

RELATED

Murray’s attorney did not respond to emailed questions.

Crosby asked Army Times to “stop using my name in stories” and said in an email that “plea deals work both ways…I was not guilty, because I was not guilty.” He said, “no,” when asked if he was arguing that he pleaded guilty to crimes he hadn’t committed.

‘A common practice’

According to Philip Cave, a retired Navy JAG and experienced military defense attorney who serves as a director of the National Institute of Military Justice, plea deals such as these are “a common practice.” He said that, like in civilian courts, the “vast majority” of UCMJ cases are resolved outside of trial, though sex offense cases are more likely to go to trial in the military.

In courts-martial, plea deals are between the convening authority — the general whose command is trying the case, advised by their staff judge advocate — and the accused. An Army spokesperson noted that the convening authority “must consider” input from the victim, but they’re not obligated to follow their wishes.

Cave explained that the plea agreements are more common when the prosecution has doubts about success, or if they lack the time and resources to take a case to trial. Conversely, the accused, on the advice of defense counsel, are often eager for a deal when they think the evidence could lead a judge or panel to convict at trial.

And some cases without strong evidence make it to trial due to the insistence of the commanders that oversee courts-martial, explained Cave.

The seasoned defense attorney argued that pretrial agreements, even those that allow defendants to plead down to non-sexual charges, have their benefits: a relatively quick resolution to the case, as well as a predictable sentence. He noted that the government must consult with victims in such cases, and many support deals in order to get closure.

In some cases, prosecutors and victims either don’t fully understand or don’t support deals, explained retired Col. Don Christensen, who once was the Air Force’s top prosecutor but is now head of Protect our Defenders, a non-profit that aims to end sexual violence in the military.

Unlike the civilian justice system, the prosecutors, many of whom are captains, are not directly involved in deal-making, said Christensen.

The former top Air Force prosecutor argued that some staff judge advocates lack the prosecutorial experience to effectively gauge whether a case could be lost at trial. Christensen also said that “senior officers and senior enlisted people” often get a “pass” and are allowed to leave with their retirement benefits intact.

Judges can’t reject deals either, except for narrow circumstances.

The legal experts think it’s too soon to tell how the service’s ongoing work to establish an independent prosecution office for major crimes — including sexual offenses — will impact plea deals. Cave said it will take several years after full implementation to understand the overall effects of the change and to then decide on modifications.

The service’s independent prosecutor, who will be a general officer who reports to the Army secretary, will have “exclusive authority to enter into plea agreements” for covered offenses, Army spokesperson Sgt. 1st Class Anthony Hewitt told Army Times in an emailed statement.

The NIMJ director said most military law experts believe that the new independent office will focus on high-quality cases — which could leave prosecutors less likely to cut deals and defense attorneys more eager for them.

Cave thinks the answer won’t be clear “for a few years” after the office takes over prosecutions.

One thing is clear, though: victims from the Crosby and Murray cases aren’t happy with the current system.

‘The court fucked me over’

Melissa, a former Louisiana National Guard NCO, told Army Times in a series of phone interviews that prosecutors gave her the impression that Crosby would have to register as a sex offender as part of his plea deal, which she said officials pressured her to support. She asked that Army Times only publish her first name — she has since moved and started a new career.

Army Times covered Crosby’s conviction and subsequent retirement in May.

“There’s so much more to that story,” Melissa explained, venting her frustration.

“The SHARP [sexual harassment/assault response and prevention program] did their job,” she said. “[The lawyer] told me that this motherfucker was still supposed to be registered as a sex offender.”

Asked about situations like Melissa’s, Christensen of Protect our Defenders decried a “lack of honesty when [command officials] are talking to victims to try to convince them to do deals,” before adding that some prosecutors may not understand state sex offender registry laws.

According to online court records, Crosby told Melissa twice — each time with witnesses around — about his plan to assault her during her promotion ceremony after learning that she had been selected for sergeant.

He also told another NCO about his intentions. That led Melissa to ask not to have a ceremony — but that didn’t stop him from assaulting her the following day in the supply room of their small base in Jordan.

According to a prosecution motion, he “approached [Melissa], told her to stand up, placed the rank in front of her chest, leaned in to grab the rank with his teeth...then placed his face between [Melissa]’s breasts...[and] vigorously moved his head from side to side between [her] breasts while still holding the rank with his teeth.”

But the problems began before the promotion ceremony, she explained, contributing to what she sees as a double standard for disciplining senior personnel.

Melissa said Crosby was her company commander in the years leading up to the deployment, and he’d always paid close attention to her, including an assignment as his driver.

“It was an easy job,” she recalled. “He seemed like a good guy — like an easygoing commander — everybody wants an easygoing commander instead of an asshole, you know? If things would start to go into inappropriate comments, I would laugh it off and not say anything.”

She eventually earned a slot as the company’s supply sergeant despite only being a specialist, which led to her being selected to go on an advance party for the 256th Infantry Brigade Combat Team’s 2020-2021 deployment to the Middle East. Melissa’s unit, Company H, 199th Brigade Support Battalion, went to Jordan and supported one of the brigade’s infantry battalions — and Crosby had been assigned to the advance party as the battalion’s new logistics officer.

“The whole time we were on [advance party], the comments got worse. They got more sexual,” she said. “I couldn’t run from it. I was fucking stuck there.”

After the rest of her unit arrived, Melissa said, Crosby’s interest in her became widely known, leading some of her junior peers to spread rumors and shun her.

“Nobody told him anything like, ‘Sir, you need to check yourself;’ nobody reported anything,” Melissa added. “Even the [assault] witness didn’t want to be involved. Nobody was reporting shit because nobody gave a fuck.”

Not even the May 2021 promotion ceremony assault changed many of their minds, she recalled. Crosby was transferred to another base shortly after it occurred.

“It was as if people felt sorry for him,” she said. “They were more concerned about Crosby [than me], and though that situation was fucked up…they’re probably happy that he fucking retired.”

Melissa thinks that if she had done something similar to Crosby — publicly declared her intentions to touch another soldier sexually and then followed through on them — she would have been “crushed” by the military justice system.

She also blasted prosecutors in her case for making her feel “manipulated to [accept] an easy deal for him” that allowed the captain to retire after 30 days’ confinement.

“I can understand a lawyer trying to convince Crosby of taking a deal,” Melissa said. “But like why are you trying to convince me of a shitty deal?”

Early proposed deals would have allowed Crosby to retire without punishment and plead guilty to merely grabbing her shoulders, she added. She didn’t support the final deal, either.

Melissa’s special victims counsel submitted a formal memo for the court-martial’s convening authority, 1st Theater Sustainment Command’s Maj. Gen. Michel Russell, explaining her opposition to the deal, which she shared with Army Times.

“[Melissa] does not agree with the Article 120 offense, Abusive Sexual Contact, being reduced to Article 128,” a non-sexual assault consummated by battery, the memo said. “[She] is prepared to continue to cooperate with the Government and testify at court-martial.”

But she retracted that memo after cajoling from officials, she explained. One lawyer told her that she might not win at trial despite there being another NCO who witnessed the assault.

“When someone does something fucked up and a witness [is] involved, how is there any argument?” she asked. “[But] I felt I had to take the deal.”

With Melissa’s reluctant support, Crosby’s plea deal was accepted. He served his 30 days behind bars and retired with full benefits on March 31.

A spokesperson for 1st Theater Sustainment Command, Maj. Dan Parker, told Army Times in an email that Russell properly considered “the recommendations and input of the chain of command, the staff judge advocate and the survivor” in the Crosby case. He emphasized that Crosby was convicted “of a federal assault crime and sentenced to a month in confinement.”

“Capt. Crosby’s court-martial conviction and punishment ensured he was held accountable for his actions,” said Parker. “Soldiers must be able to trust their leaders. Capt. Crosby violated that trust.”

Melissa disagreed with the command’s assessment, arguing the justice system failed in her case. In the months since, she’s started counseling with the VA for issues stemming from the assault, the social fallout from reporting it and her struggle to find justice through the courts.

“The court fucked me over.”

‘I was set up to fail by the government’

Clinton Murray’s alleged victims have similar sentiments.

Army Times conducted a series of phone interviews with both women whom Murray was accused of assaulting, though the former cavalry squadron CSM was acquitted of sexual assault and instead convicted of fraternization in both cases.

One, then-Pfc. Morgan Masters, elected to speak under her name. The other, a junior officer, asked that her name not appear in the story. Both deployed with 3rd Squadron, 73rd Cavalry in 2017 with Murray as the unit’s senior enlisted soldier.

Court records reveal that Murray’s first court-martial, in January 2020, was for allegedly sexually assaulting Masters in his Kabul office during that deployment. Murray beat that allegation: a panel acquitted him of sexual assault and maltreatment. They instead convicted him of fraternizing with Masters, sentencing him to a reduction to master sergeant. The command dismissed charges that he fraternized with an officer during the deployment.

Prosecutors in that trial had a challenge: there was little physical evidence. And after the trial began, they learned why. The officer with whom Murray fraternized had destroyed evidence of the reported assault, allegedly at Murray’s behest — and two days into the trial, she showed up at Fort Bragg and was ready to talk.

It’s not clear if the officer testifying at trial would have changed the outcome since she arrived too late — the panel was already in deliberations and later acquitted Murray of the assault. But the newly-demoted master sergeant was immediately put under a new criminal investigation in February 2020 to look into the officer’s allegations, which included attempting to share nude photos of the officer, blackmailing her for nude photos and coercing her into sex.

Initially, the officer was “very confident.”

“The sense I got from the government was that they [knew] they had completely screwed up…so they’re going to put so much time and effort into getting justice,” the officer said.

Masters thinks the government screwed up, too — by failing to secure the evidence that the officer destroyed after Murray learned of the sexual assault allegation.

“They didn’t protect me and my legal process [by having] evidence handled properly,” she argued.

According to his charges, Murray was aware of the assault allegation against him by Dec. 10, 2017. Prosecutors alleged he told the officer to destroy the evidence sometime between Dec. 11 and Dec. 14, though that charge was dismissed. It’s not clear what measures the unit took to protect evidence of the alleged assault, and it’s not clear why they failed.

Murray caught more charges when he allegedly faked signatures on clearing paperwork, left Fort Bragg and collected his pension for three weeks. The Army said that was in error and ordered him back. Murray refused, suing the Army and losing before being dragged back on a deserter warrant in August 2020.

Ahead of the second trial, Masters told Army Times her experience had “been this awful feeling of relying on the other victim…so I can get my justice.”

But the officer’s case got complicated. A disagreement over a Post Traumatic Stress Disorder intake form from the Veterans Affairs administration being allowed into evidence, despite court-martial rules prohibiting mental health treatment records from being subpoenaed, led her to sue the Army and VA in an effort to block their disclosure to the court — and to the public. Her appeals were denied.

The former officer explained to Army Times that the prosecutor who had initially been gung-ho about going after Murray had left the division as well.

“The one person who was on my side from the prosecution team was removed, and so that kinda just stopped the case,” she said. “I felt like it just became another case on the docket and that the government just wanted to get through…They lost their fire to want to fight for this and it just became a burden on them to prosecute this guy.”

When the government approached her about a plea deal, her feelings were complex. She was ready for the five-year ordeal to end, especially after losing the fight over her psychiatric records, plus she knew the sexual assault charge might be difficult to win at trial. One thing was certain, though: she wanted him to at least plead guilty to the nude photograph charges.

According to a stipulation of facts from the trial, Murray admitted to soliciting nude photos of the officer until she capitulated out of fear that he would expose their unlawful relationship. When she tried to end the relationship, he threatened to “expose their relationship, including nude photos of [her].”

But Murray wouldn’t take a deal that included a registered sex offense or a felony, according to the officer. And any deal would have to let him keep his retirement.

He got the agreement he wanted, pleading guilty June 15. The sex crimes and desertion charge were dismissed, and Murray pleaded guilty to a series of minor offenses that included simple assault, fraternization, dereliction of duty (for misrouting his clearing paperwork) and discrediting the Army through sexual harassment.

Murray was also reduced to sergeant first class and sentenced to 90 days’ confinement, less one day of pre-trial confinement credit.

The officer, while “validated” by the fact that Murray ultimately went to jail, is furious with how the process played out.

“He gets to retire after all of this. After all that he’s done…he basically gets to spend 89 days in prison, retire as a sergeant first class, and still get benefits,” she said. “I was set up to fail by the government.”

Masters, who received a medical retirement due to mental health problems stemming from her experience in Afghanistan, is also disappointed. She feels that Murray was held to a lower standard than she would have been, especially on the dismissed desertion charge.

“As the victim, if I had gone [absent without leave]...I would have been eaten alive and put in some military prison for doing the exact same thing,” she said.

“I want to reiterate that I’m not mad at [the officer],” Masters asked Army Times to print. “She took her power back from what he did to her…I think the blame should be placed on the Army and how they didn’t really protect either one of us from him.”

Davis Winkie covers the Army for Military Times. He studied history at Vanderbilt and UNC-Chapel Hill, and served five years in the Army Guard. His investigations earned the Society of Professional Journalists' 2023 Sunshine Award and consecutive Military Reporters and Editors honors, among others. Davis was also a 2022 Livingston Awards finalist.