"My lover’s dead. My lover is dead.”

It was one of the first thoughts that ran through Kathleen Bourque’s mind as she was given unfathomable news: Her fiancé had been killed in a military training accident.

It was May 9.

Bourque and 1st Lt. Conor McDowell already had wedding plans for September, but she was awaiting an engagement ring that the 24-year-old Marine light armored reconnaissance platoon commander was having custom-made. He was planning to present it to her after he finished his Marine Corps training exercise at Camp Pendleton, California.

The Marine would never get the chance to give his fiancée the ring in person.

His mother presented it to Bourque at his memorial service, held at Pendleton when they remembered him, and that fateful day.

On May 9, the LAV that McDowell and his crew were operating had slowly crept into nearly six-foot tall vegetation that obstructed the driver’s vision.

The Marines never saw the ditch until it was too late.

Their LAV plummeted down a 15-foot washout and rolled upside down, a command investigation obtained by Marine Corps Times detailed.

A Marine official, who spoke to Marine Corps Times on condition of anonymity, confirmed that McDowell heroically used his last moments alive to alert his crew that the vehicle was about to roll. The investigation noted those actions may have spared further or more serious injury to the Marines under McDowell’s command.

McDowell was killed in the accident and several of his crewmembers were injured.

A lover lost

Bourque heard the tragic news from friends the day after the incident. Later on May 10 she headed for Camp Pendleton, California, to speak to her fiancé’s command.

“If he’s [McDowell] at Pendleton, I have to go there, I have to be there with him,” Bourque told Marine Corps Times in an exclusive interview.

“We were supposed to have a family together,” Bourque said. “That’s when I realized my future with him had died with him. That’s a hard pill to swallow.”

“The one time that I had ever really truly known real joy and just complete unadulterated love was just gone.”

Bourque and McDowell’s life together was cut tragically short following the accident. But the two fell in love almost instantaneously after connecting on the dating app Hinge around June 2018.

“We fought like hell to make it work,” Bourque said.

McDowell had just graduated the Corps’ arduous Infantry Officer Course in Virginia and was headed for Camp Pendleton in California but he decided that he needed to spend time with Bourque before his next assignment.

An 800-mile drive later, McDowell was standing in Bourque’s living room in North Carolina sporting a Captain America T-shirt and khaki pants, Bourque said, describing the first time the pair met in person.

“In that moment it was as if I was looking at the only person I had ever met who I was able to see my soul so clearly reflected,” She said. “We imprinted on each other.”

After four days of spending time together in North Carolina, the couple made a fate decision against the advice of some friends and family — Bourque would move to California with McDowell.

“I’ll be damned if I leave to San Diego without you by my side,” McDowell said to Bourque, according to Bourque’s recollection of the day.

She packed a small carry-on bag and the couple hit the road on the way to California, she detailed to Marine Corps Times.

“We had the world against us,” Bourque said. “We threw all our cares to the wind and just went for it. That is the way we loved…with an intensity that is incomprehensible.”

Bourque said McDowell loved his job and cared deeply for the Marines under his command. “He loved the something fierce,” she said. “He had a fire in his soul.”

RELATED

“I am going to make sure we have the most dangerous platoon,” Bourque said McDowell told her one day about his LAV platoon.

Bourque is still pressing for changes to help save service members’ lives in the wake of her fiancé’s tragic accident.

“I was destroyed, my entire world, my entire future was just stripped from me,” she said.

A command investigation exonerated McDowell of any wrongdoing in the LAV rollover — faulting instead a “terrain feature that became too late to avoid.”

McDowell and his LAV platoon set out on a route reconnaissance exercise following a May 9 order to recon Canyon Road aboard Pendleton in preparation for a division-sized movement

McDowell eventually had the vehicle drive off road into tall vegetation. Moving off road and using vegetation for cover and concealment is not uncommon for Marines with LAR.

Light armored reconnaissance Marines are taught in the leaders’ course that “roads are dangerous areas” that should be avoided to eliminate “dust signatures,” the investigation reads.

McDowell’s vehicle crawled at a walking pace as the driver couldn’t see more than five feet in front of the vehicle. A corporal in the vehicle stood up and yelled for the driver to halt, but it was too late — the vehicle started to drop.

In his last seconds alive, McDowell prepared his Marines and shouted the warning for an impending rollover — helping prevent further injury to the team.

The investigation said there was an inability to distinguish the ditch on the map.

Fighting tactical vehicle accidents

McDowell is one of four Marines who died in tactical military vehicle rollovers during training exercises in 2019. It’s a slight uptick in noncombat related tactical vehicle fatalities for the Corps.

Marine Raider Staff Sgt. Joshua Braica, Lance Cpl. Hans Sandoval-Pereyra and Pfc. Christian Bautista also lost their lives to tactical vehicle accidents in 2019. Braica was killed in a Polaris MRZR rollover in April, and Sandoval-Pereyra and Bautista died in Humvee related incidents.

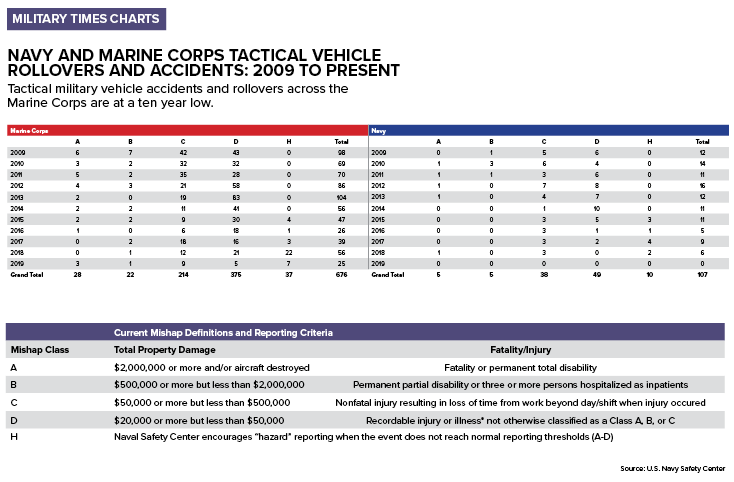

However, data provided by Naval Safety Center indicates Marine tactical vehicle mishaps are at a nearly 10-year low.

Family members of lost loved ones and some members of Congress say they remain skeptical of the Corps’ accident reporting accuracy.

The Navy reports and classifies mishaps on a scale from A to D, which is a fatality or $2.5 million or more in damages; to a recordable injury or $25,000 or more in damages.

Incidents outside that scope are recorded as “hazard reporting,” according to Stephanie Slater, a spokeswoman with the Naval Safety Center. But the accuracy of that reporting relies on individual commands, which is not always complete, she said.

McDowell’s father, Michael McDowell, and Bourque have been on a war path to push Congress and the military to act on military vehicle rollovers.

Bourque told Marine Corps Times that during her numerous visits to Capitol Hill, lawmakers and congressional staffers were “appalled” by the possibility that some rollover accidents may not have been reported.

The House Armed Services Committee did not respond to a request for comment from Marine Corps Times.

Even if an accident or rollover results in no injury or damage, reporting it may provide evidence or indicate trends that could help determine the primary cause of these types of accidents, Bourque said.

“The reporting is a real issue and we pushed GAO [Government Accountability Office] to focus on that too. There is no common standard on reporting.” McDowell told Marine Corps Times.

On Oct. 24, the House Armed Services Committee confirmed that the GAO would conduct a formal inquiry into the high number of fatalities resulting from military vehicle rollovers.

But it may not just be reporting that’s the problem.

McDowell argues there are real issues with training and safety standards coupled with years of the military slapping upgrades and new armor on tactical vehicles that have potentially made them more difficult to handle on rough terrain.

The LAV operated by McDowell’s son is nearly 40-years-old and has undergone several upgrades to boost survivability in an effort to keep the vehicle operating on the ever rapidly changing battlefield.

RELATED

Upgrades have included a new version of the LAV that boasts a new turret capable of firing anti-tank guided missiles known as the TOW. Other upgrades have included an automatic fire suppression system, and a ballistic protection upgrade, among other updates, according to Marine Corps Systems Command.

A request for information submitted by the Corps in 2019 is also seeking to add a long-range organic precision fires capability. The Corps ultimately will replace the LAV with the new armored reconnaissance vehicle, but a timeframe for fielding is still undetermined.

Moreover, to counter the onslaught of roadside bombs placed by Iraqi and Afghan insurgents during the early outset of the “war on terror” the U.S. military and the Corps began slapping armored kits on Humvees and 7-ton MVTR trucks prior to the fielding of the Mine-Resistant Ambush Protected, or MRAP vehicle.

A report for Naval Postgraduate School, authored by now-retired Marine Col. Walter Yates, detailed that the rush to up-armor 7-ton trucks without subsequent proper training or simulators resulted in avoidable accidents.

“As the IED became the primary lethal threat to troops in Iraq we rushed to up-armor our vehicles. The “Armadillo” armor kit that was applied to the 7-ton MTVR truck was a huge improvement in survivability for troops riding in the back,” Yates said in his report.

“Within a week of the first two trucks being delivered the driver of one truck rear-ended the truck in front of him because he was following too closely and the brakes would not stop the vehicle before it collided,” Yates wrote.

Another 2012 report prepared for the Institute for Defense Analysis and authored by Anthony Ciavarelli found that between November 2007 and September 2008 there were 122 vehicle accidents involving MRAPs in Afghanistan and Iraq.

In 63 of those cases, or 51 percent, the vehicle experienced a rollover. Most of these incidents were believed to be the result of poor training, according to the report.

“In most cases, drivers were unaware of the hazard, such as poorly constructed bridges and berms, and when encountering an imminent rollover, drivers over corrected steering and were not trained to initiate counter maneuvers,” the report reads.

In response to the high number of rollovers overseas the Corps and U.S. military began to push a number driving and egress simulators.

The Corps is currently replacing its driving simulators with the “more capable and technologically advanced” Marine Common Driver Trainers, or MCDT, according to officials with Marine Corps Combat Development Command.

The new simulator will support the Humvee and its replacement the Joint Light Tactical Vehicle, or JLTV.

The JLTV also has an egress trainer to train Marines how to escape from a vehicle that has rolled over. That trainer is currently being fielded, MCCDC said.

But one former Marine officer criticized the Corps’ prioritizing of an egress trainer for the JLTV over a driving simulator.

“Rather than invest in a simulator to teach Marines not to wreck a JLTV, the program office decided to invest first in a trainer to teach them how to escape from a wrecked vehicle,” the former Marine officer told Marine Corps Times on condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to speak on the record.

“To illustrate just how crazy that is, it would be analogous to the PM [program manager] for the F-35 taking the position that rather than invest in a high fidelity flight simulator they are going to save a ton of program budget by just buying ejection seat trainers, the former officer said.

The source who spoke to Marine Corps Times currently works as an independent consultant pushing technology to the DoD.

The LAV currently has four full motion driver simulators on site at the Light Armored Reconnaissance Training Course at Camp Pendleton, California, according to MCCDC.

Planning is underway for simulator development for the new Amphibious Combat Vehicle, according to Marine Corps Systems Command.

Shawn Snow is the senior reporter for Marine Corps Times and a Marine Corps veteran.