Tim O’Brien’s list of writing accolades is extensive. The Vietnam veteran and National Book Award winner’s dissection of the war in Vietnam, most prominently illustrated through 1990′s “The Things They Carried,” has spawned meticulous critiques and commendation by audiences that range from middle and high school students to military historians and combat veterans.

By the book’s 20th anniversary in 2010, the historical fiction based on O’Brien’s frontline experience in Vietnam had surpassed 2 million copies sold, its immeasurable impact prompting the Library of Congress to name it one of the 65 most influential books in U.S. history.

But after writing “July, July” in 2002, Tim, now 74, stepped away from the keyboard. Confounded by America’s involvement in wars that too closely mirrored his own, Tim has since opted to spend his time being a father to his two children born later in his life.

Writing, however, is in O’Brien’s blood. And after nearly two decades, he began working on “Dad’s Maybe Book,” a final project he hopes will allow his children to hear their father’s voice in its pages long after he’s gone.

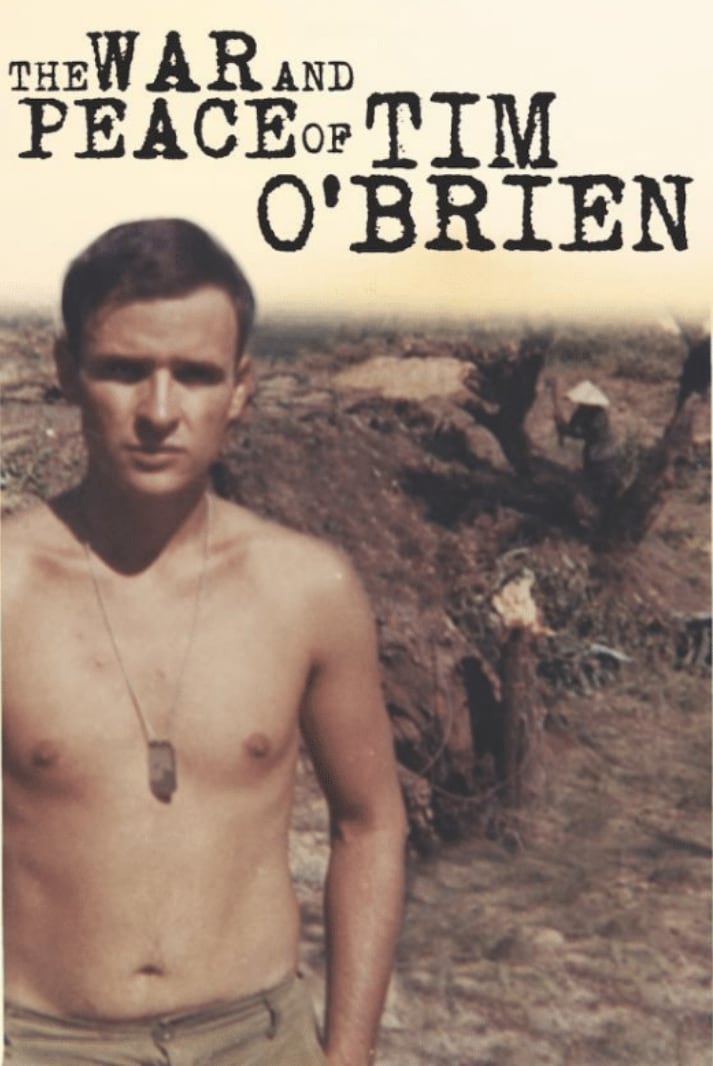

The undertaking of writing that book is the subject of “The War and Peace of Tim O’Brien,” a documentary “about the struggles of a world-renowned war writer [that] illuminates the everyday ties between duty, art, family, and the trauma of war,” the film’s synopsis reads.

O’Brien spoke with me about the inspiration behind his final book, the perceived meaning of his life’s work, the trauma he’s endured, and his anticipation of confronting his own mortality.

Pre-order “The War and Peace of Tim O’Brien” now on iTunes.

Your career has revolved around dissuading others from going to war for futile reasons. What was it about your experience during the Vietnam War, whether at home or abroad, that first shaped that approach?

One thing I can say is that I’m not a complete pacifist. There are times when force is necessary. Unfortunately, Vietnam didn’t feel like one of those times.

The whole country was divided. Was a war right or wrong? Congress couldn’t make up their minds. Rhodes scholars disagreed, hard hats disagreed with flower children. The country was divided, much more so than in our wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. My family was divided, too. My mom was for the war, my dad was against it. So, you’re 22, you love your country. You’ve grown up on service to country. What the hell do you do when the best you could say about Vietnam was certain blood was being shed for uncertain reasons?

That’s the boat I found myself in. I love my country, but I didn’t believe in my country’s war. It’s a little bit now like having children. I love my children, but I don’t love everything they do. (laughs)

I ended up going to war as a foot soldier and was totally unequipped for it. I’d hated Cub Scouts and Boy Scouts and dropped out of both of them. I didn’t like bugs, I didn’t like sleeping in the rain, and I didn’t know one end of the rifle from the other. I mean that almost literally — I couldn’t tell if my weapon was loaded or not during firing range practice.

So, I had to learn when I got there. I wanted to stay alive and I wanted to keep my friends alive, but I was playing catch up. On top of that, I didn’t like what we were seeing or what we were doing. It seemed to me we were doing the opposite of what our country was told we were doing. We weren’t winning hearts and minds. We were peeing in people’s wells, trampling their rice paddies and burning hooches.

I remember a little girl being carried into our perimeter by an old man. Nobody intended to kill the little girl, but there she is. She’s maybe 7 years old. You couldn’t really tell because the bullet had hit her in the head. You carry all this stuff day after day after day.

That goal of deterring people from war is one that, as you say in the documentary, has left you “consistently disappointed.” We’ve yet to experience time this century sans involvement in multiple wars. How have those conflicts impacted your perception of your life’s work?

I just wish my country would be more careful about killing people and not so bellicose in our rhetoric.

If you’re a farmer in Dubuque, Iowa, you’re not going to like it if al-Qaida or ISIS come and burn your houses down, pee in your wells or kill your children, even if by accident. Why should we expect others to?

And yet, we do expect others to. Then we expect them to look at us as saviors and saintly and clean-handed. I can’t imagine any radical militias in Iraq or Afghanistan raising their hands up and surrendering just to accept their place in a democracy. I just can’t imagine a happy outcome, just as 50 years ago it was hard to imagine Hồ Chí Minh and other committed revolutionaries surrendering. And now, just like back then, it’s hard to believe anything our politicians have tried to sell us.

This thought of curing people of being who they have been for centuries, then believing they will adopt our standards or values, just doesn’t seem possible. It’s up to the people one way or another, and I just don’t believe bombs and drones are going to do it for them.

In the film, you tell a story of young a man who’s contemplating joining the Marines. After hearing you speak at a function, he credits you for helping to make his mind up — surprisingly, in favor of joining. Does this sort of thing ever give you the sense that those who read your words are simply hearing them versus actually taking them to heart?

I think half of it is just what you said — they’re not truly listening. They’re hearing words and fitting what they’re hearing into a fabric of their own construction.

In Vietnam a friend of mine, Rodger McElhaney, was squashed by one of our armored personnel carriers. We were in a rice paddy taking fire and we jumped behind these APCs for cover. The track started backing up and we could barely move, so my friend winds up at the bottom of a rice paddy and the rest of my company has to probe for his body.

Let’s say you tell that story and you’re in the audience and are contemplating joining the Marine Corps. It’s human nature to think, “Maybe I would do better than O’Brien in that situation. I’d be able to take it. I’m tough enough.”

Stories, whether they’re true or made up, are processed through the filter that individuals bring to them. And that’s evident because this example has happened to me 20 or 30 times. Someone’s on the fence about joining, listens to me speak, then tells me they feel better about their decision to join.

I just go back to my hotel, look in the mirror and think, “You poor yo-yo, you failed again.”

But I’ve become so inured to it, this realization that people extract things from books, movies or magazine articles that are really unexpected, and the rest they sort of push to the background. It’s totally human, but it’s nonetheless always shocking.

Do you feel any of that “I could do it better” hubris is influenced by today’s seemingly blanket application of troop support? Some have argued that, for decades now, we’ve been overcompensating for the maltreatment of Vietnam veterans to the point of hero worship — if you’re in uniform, you can do no wrong.

There is a kind of idolatry and hero worship. And in one sense, if you lose your legs, brain, or ears to a war, you’ve done something most of us don’t want to do. But then there’s this homogenized view that all people who are in uniform are white hats and have never done wrong.

Anybody who has actually been in combat or in a war zone knows that’s not true. There are people you despise. You know, the fucker you have to salute who’s telling you to do the most stupid thing possible. It’s like he stayed up all night thinking, “What is the stupidest thing I can tell a guy to do tomorrow? I’m going to do that.” And you don’t think of that guy as a white hat, you think of him as an asshole.

Soldiers are not this pasteurized, homogenized carton of milk where we’re all identical. There are great people you meet during a war, people you adore, and there are people you despise. And there are plenty of grades again in between.

So, it is a strange reversal where we seem to overcompensate for the mistreatment of earlier veterans by making them the subjects of unconditional adulation.

In the film we learn about some of the trauma you’ve experienced — from growing up with an alcoholic father to getting wounded in Vietnam. You say one of the best ways to escape trauma is through fiction or fantasy. Is this mechanism one of the reasons you chose to fictionalize elements of “The Things They Carried?”

I think so. In a work of fiction, you aren’t frozen into what happened. You can write about what almost happened or what could have happened.

Anybody who’s been under fire is kind of hoping for a miracle. You don’t know what it is, you don’t try to verbalize it, but you’re hoping something will save you. So, you go into a fantasy world. Maybe late at night you’re guarding a perimeter and staring out into the black. You can only do that for so long before fantasy takes you back home to your girlfriend or having spaghetti with mom and dad. Then you’re suddenly back in the black. You sort of flip back and forth as a way of escaping the horrors around you that you can’t process.

People in concentration camps escaped into their heads by looking at something as simple as a robin in the middle of Auschwitz and pretending they were that bird. I think it’s human nature — and maybe even the body’s chemistry — of having the gift of imagination to be able to, at least temporarily, stay sane in the midst of insanity.

When it comes to your relationship with your children, how do you see them carrying the burden of your trauma?

Like other veterans who have seen actual combat, I sometimes just glaze out on occasion at the dinner table, just staring into space and remembering something. They’ve grown used to this glassy-eyed guy who will sometimes leave them for 20 seconds in memory. They see the lasting impact on me of something that happened 50 years ago and now understand that wars do not end when the peace treaty is signed.

Wars continue in the heads of soldiers, but they also go on and on in the heads of the Gold Star mothers and families who lost children.

Even now, 50 years later, some old woman will wake up at 2 a.m. and say, “Where’s my baby?” And her baby’s been dead 50 fucking years. But it’s still there. For her that war is not over.

In many ways, the children, sisters, brothers, lovers, and parents are worse off than the dead. We tend to count casualties in war by the number of dead soldiers, but the ripple effect goes way beyond us.

For you, the war’s lingering presence has almost been renewed, as you discuss in the film, through confronting your own mortality and the feeling that, on borrowed time, certain goals are no longer a certainty, but a possibility. How does that parallel to your war experience?

It’s like revisiting Vietnam as an old man, where death was proximate, waiting for you after every step. Now, 50 years later, it’s back again.

In your middle years you’re able to push it away — you have jobs to do, children to raise, golf balls to hit, all the things that get in the way of thinking about it. But in old age the proximity of it is on you again.

It’s not a macabre thought — finality is everybody’s fate. We know it intellectually, we forget it or suppress it emotionally. But in a war, maybe even in a pandemic, but certainly in old age, it’s back, and that wolf is howling again. Now, it’s harder to look away from. Just as in Vietnam, it was hard to look away from death. It was all around you, it was in your head.

And so, it’s a strange revisiting, but it’s not all bad. In a way it’s great to be conscious of the precious moments ahead of you. They’re precious in a way that they weren’t before. And there’s an urgency that’s kind of nice, as it is with writing this book. I’d rather be with my kids, but I wanted to write them this gift so that when I’m gone, they’ll have, at my age, something I wish I’d been given by my dad.

I know for many people it’s going to seem macabre, but I’m not obsessed by death — I’m motivated by the preciousness of what time is left to extract what I can from the world of the living.

On that note, you point out the irony that the entire content of your obituary will describe you as a war writer, that the worst thing that’s ever happened to you, the catalyst for “intense moral failure and shame,” is what you’ll be remembered for. How would you want people to remember you?

As a writer, not a war writer. “The Things They Carried” is as much a peace book as it is a war book. We don’t do it to Joseph Conrad by calling him an ocean writer. You don’t do it to Shakespeare by calling him a king writer. I’m just a writer. I work on sentences, and that’s hard to do.

When I write, I’m not necessarily thinking about Vietnam. I’m thinking about constructing a sentence that will convey whatever I’m seeing. People who aren’t writers don’t understand how hard it is to put together decent sentences. Because at the end, all you have are those 26 letters in our alphabet, and with those 26 letters and those punctuation marks you’ve got to convey emotion and scenery and the physicality of the world. It’s a hard fucking job.

I wish I’d become a plumber (laughs), but that’s what I do instead.

J.D. Simkins is the executive editor of Military Times and Defense News, and a Marine Corps veteran of the Iraq War.