CHATTANOOGA, Tenn. — Like many twins, the Markham brothers shared secrets. But most twins’ secrets probably don’t involve duping the United States military.

Wilbourne Markham said his twin brother, Weldon, was determined for them to join the military in 1952 (Wilbourne thinks it’s because he watched too many John Wayne movies). But Wilbourne had a stipulation: they had to stick together.

After securing assurance from President Harry Truman and the U.S. Air Force that twins would never be separated, they made the trek from their home in Chattanooga to Knoxville for their physicals.

Wilbourne passed the test and turned to celebrate with Weldon, whom he thought was right behind him. Instead, he found Weldon crying off to the side.

“He said, ‘They don’t want me. I’ve got a heart murmur,’” Wilbourne recalled, replying, “'If they don’t want you, pal, they don’t get me.'”

The boys came home and decided Wilbourne would go back and take the physical again in his place. He passed as Weldon.

“The next day we both raised our hands, and off to the Air Force we went,” Wilbourne said.

Only once in 41 years of service were the twins separated. It was during their first deployment near Okinawa for the Korean War. Weldon showed his commanding officer the president’s letter and cited the Air Force regulation regarding twins. The officer happened to be from Atlanta and took a liking to Wilbourne’s accent. The twins were reunited within two weeks.

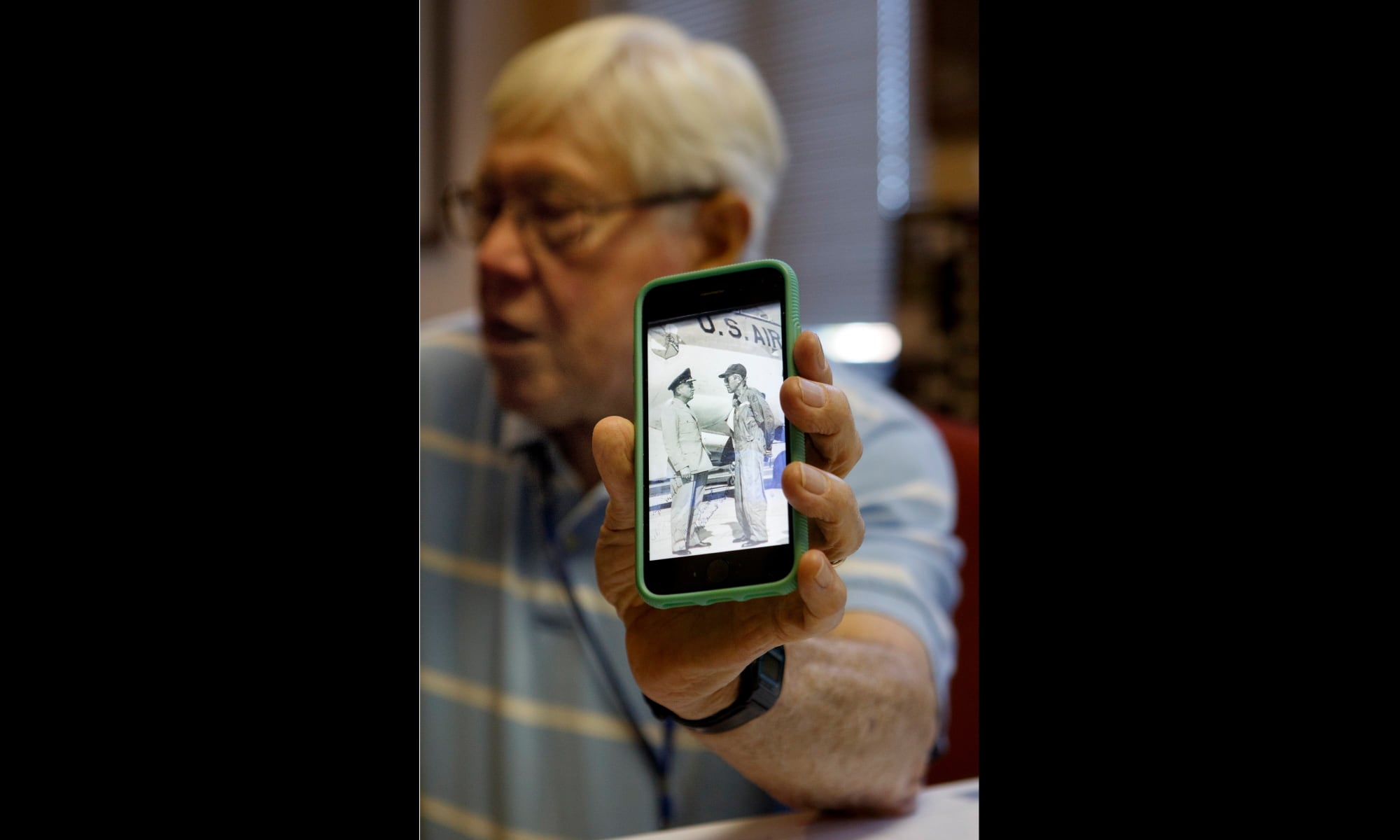

A highlight of Wilbourne’s early military career was working for Maj. Gen. William H. Blanchard Jr. — the backup pilot for Paul Tibbitts, who as a colonel who piloted the Enola Gay, dropping the “Little Boy” atomic bomb on Hiroshima. Blanchard went on to become a four-star general and vice chief of staff of the Air Force. When Wilbourne told Blanchard that he wanted to go to college rather than enlist, the general said that’s what he should do.

“I always appreciated that,” Wilbourne said.

The twins moved into the active reserves to attend college at the University of Tennessee at Knoxville, where Wilbourne majored in political science and minored in history. They moved back to Chattanooga after graduating and remained in the reserves.

Throughout the years, they traveled regularly to train at Maxwell Air Force Base in Montgomery, Alabama — not far from the small town where they grew up, Chisholm, Alabama. At Maxwell, their mentor, Chief Master Sgt. Dan Zarazua, cross-trained them to become medics. The twins learned to everything from treating acute illnesses and gunshot wounds to delivering babies at the base’s hospital.

Wilbourne was called to active duty again when the Gulf War began in 1990. Weldon desperately tried to volunteer, but wasn’t accepted. When Wilbourne reached his initial post at England Air Force Base in Louisiana, he found out the Air Force had called him by mistake. It was actually Weldon that they wanted.

“I volunteered to stay, and he came down (from Chattanooga) in two weeks.”

Wilbourne served as the non-commissioned officer in charge of the family practice clinic, and Weldon was the non-commissioned officer in charge of the OB/GYN surgical clinic as they waited to be called to combat. However, the war ended sooner than expected and they came home to Chattanooga.

Wilbourne received numerous medals for his service, including the United Nations Service Medal, the Korean War Service Medal and the National Defense Service Medal with a star that indicates he served during two different conflicts. He was honorably discharged in 1994 as a master sergeant.

Outside of his military service, Wilbourne was a longtime educator. He taught history and civics at Dalewood Middle School and Brainerd High School before becoming an assistant principal at Hixson High School. Weldon worked for the city of Chattanooga.

Weldon died in November 2013 due to complications from his heart murmur and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Still, nearly six years after his passing, the Markham twins are never far apart.

Weldon is buried in Chattanooga National Cemetery, where Wilbourne now volunteers every Thursday. Wilbourne also plans to be buried there one day. The twins’ older brother Leslie, a World War II veteran, is buried there, as well.

Despite all the twins had in common, there were some differences.

“When he died, he was in full dress uniform,” Wilbourne said. “I will not be. I’ll be in overalls.”

Wilbourne marched on a clear October morning from the Chattanooga National Cemetery office to visit Weldon. He usually stops by his brother’s grave on Thursday, unless his allergies force him to stay inside.

Wilbourne said it may sound cliche, but he likes working at the cemetery because he’s still serving his country. He invoked one of Mark Twain’s famous quotes: “Patriotism is supporting your country all the time and your government when it deserves it.”

“That’s the way we are,” Wilbourne said. “We love our country, but we know our government makes mistakes, because we know the history.”

He places three coins on Weldon’s headstone. A penny to mark his visit. A nickel to represent their time together at boot camp. A dime to signify their service, and then the brothers talk.

“A lot of times, it’s just between he and I,” Wilbourne said, laughing. “We have a lot of secrets.”