CAMP LEJEUNE, N.C. — Gunnery Sgt. Joseph Felix is a 15-year Marine, an Iraq and Afghanistan veteran and the father of four daughters.

But he’s also become the Corps’ most notorious drill instructor, the Marine at the center of the Parris Island hazing scandal and now the defendant in a general court-martial that began Oct. 31 at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina.

Felix is accused of improperly hazing many recruits — for example, when one recruit puked in his chocolate milk, Felix allegedly made the squad leader drink it.

And he’s also accused of targeting Muslim recruits for particularly severe abuse. A Muslim Marine testified that Felix made him simulate chopping off the head of another Marine while yelling “Allahu akbar.”

Felix was questioned in the death of one Muslim recruit, Raheel Siddiqui, who was in Felix’s platoon and who fell to his death moments after Felix slapped him in the face.

Felix allegedly told an investigator that he intentionally was cruel to recruits to make them better Marines.

“You have to hate recruits to train them,” Felix told the investigator, according to Marine prosecutor Capt. Corey Wielert. “They get three meals a day, sleep eight hours. The more you hate them, the better you train them.”

Felix’s court-martial is seen by some as the long-awaited reckoning for the death of Siddiqui, who died on March 18, 2016. Siddiqui’s throat was so swollen that day that he could not speak, but Felix made him run to one end of the squad bay and back for not shouting the proper greeting of the day.

After Siddiqui fell to the floor unresponsive, Felix allegedly slapped him. Siddiqui then ran to a nearby stairwell and jumped, falling nearly 40 feet.

Siddiqui’s death was a bombshell for Parris Island that led investigators to uncover evidence of rampant abuse of recruits by numerous junior drill instructors.

At the time of Siddiqui’s death, Felix was under investigation for prior allegations of hazing and his Parris Island regimental commander had removed him from his job as a drill instructor, according to several Marine witnesses.

Siddiqui’s family has filed a $100 million lawsuit against the Marine Corps for the wrongful death of the 20-year-old Pakistani-American from Michigan.

But the circumstances of Siddiqui’s death — and what or who caused it — will not be discussed at the trial. The military judge presiding over Felix’s court-martial has prohibited lawyers and witnesses from discussing it. The court-martial panel members who will decide Felix’s fate know that Siddiqui is dead and cannot testify. But that’s all.

“You shall draw no inference from these facts and draw no conclusions from them,” military judge Col. Michael Libretto told the panel at the start of Felix’s court-martial.

The trial was expected to last three weeks. Throughout the first week of his trial, Felix — initially a 7257 air traffic controlman — sat with a drill instructor’s stern demeanor as the prosecution claimed he was “drunk on power,” often tormenting recruits after drinking Fireball Cinnamon Whisky.

“Gunnery Sgt. Felix wasn’t making Marines,” Wielert told jurors. “He was breaking them.”

‘Hey ISIS, get in’

Allegations of hazing related to recruits other than Siddiqui is enough to send Felix to the brig for years.

Felix’s six-page charge sheet lists numerous alleged violations in which he physically abused recruits from three different platoons. He faces charges of violation of a general order, maltreatment, dereliction of duty, making a false official statement, being drunk and disorderly and obstruction of justice.

Former Marine Rekan Hawez testified that Felix slapped the barrel of a recruit’s rifle against his ear, causing it to bleed. In another incident, Felix punched a recruit directly in the jaw for making a mistake, said Hawez, who attended boot camp at Parris Island from April to July 2015.

When one recruit was caught with chocolate milk at the chow hall, Felix ordered the entire platoon to drink four to five glasses of chocolate milk each and then made them do “incentive training” exercises as punishment, Hawez said. One of the recruits vomited in his cup and refused to drink it, so Felix ordered his squad leader to do so.

RELATED

Felix’s attitude toward Hawez changed after learning that he was born in Iraqi Kurdistan, Hawez said. Afterward, Felix started calling him “ISIS” and “terrorist,” he said.

“From that point on, he knew I was Middle Eastern,” Hawez told jurors. “I felt I was getting singled out much more.”

One night, Hawez said Felix woke up recruits and ordered them to squeeze their way into a room with a large commercial clothing dryer. Hawez testified that he could smell alcohol on Felix’s breath at the time.

The recruits were laying so close together on the floor that Felix and two other drill instructors were “physically walking” on them, Hawez said.

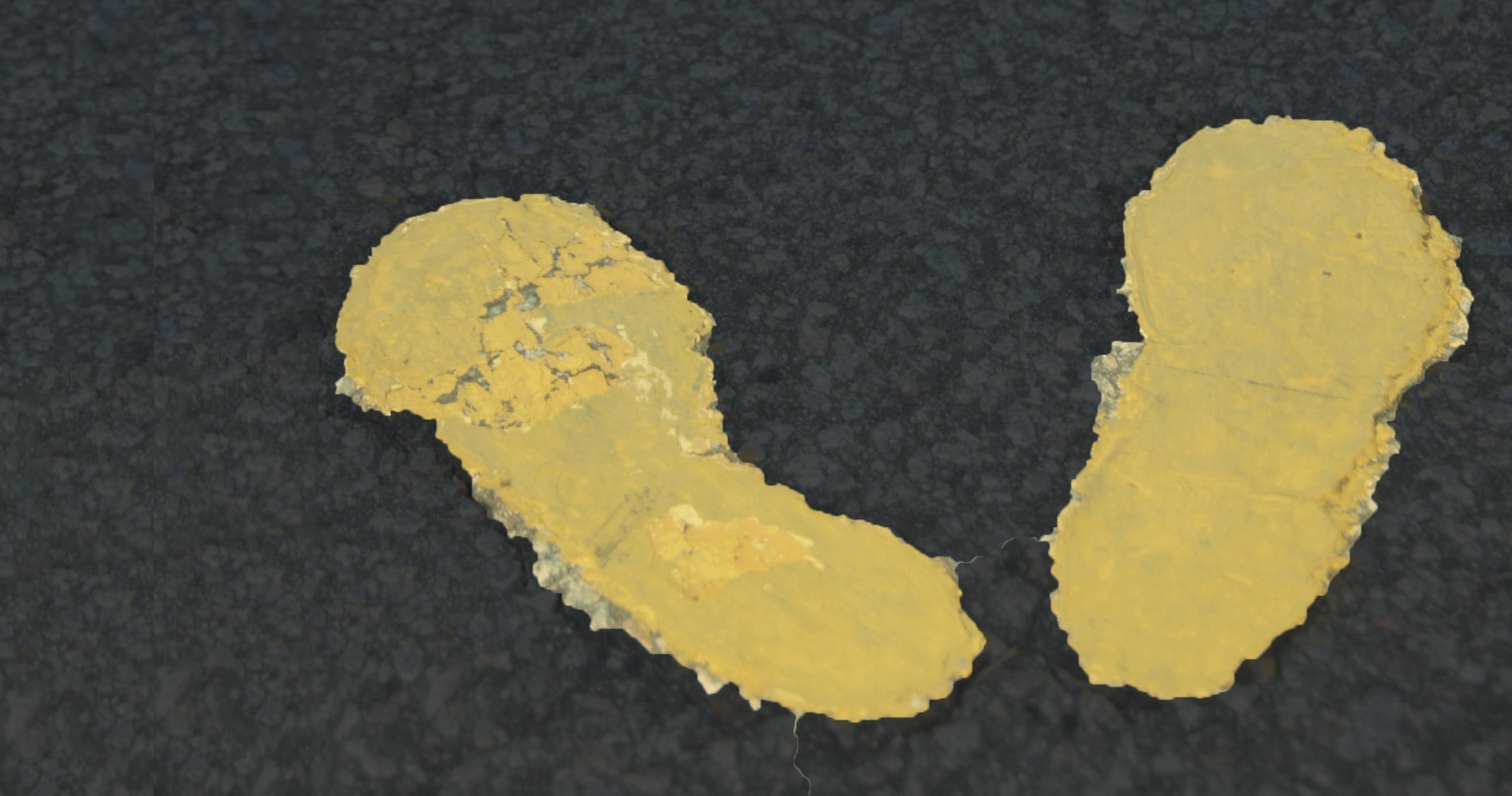

While in the room, Felix pointed to a dryer and told Hawez, “Hey ISIS, get in,” Hawez said. Hawez climbed inside and closed the door. After about 15 seconds, Felix ordered him to get out without turning the dryer on, he said.

Hawez is the second Marine to accuse Felix of forcing him into a dryer. The other recruit, Lance Cpl. Ameer Bourmeche, testified on Oct. 31 that Felix and fellow drill instructor Sgt. Michael Eldridge only let him out of the dryer after he told them he was no longer a Muslim.

Hawez said he was separated from the Marine Corps in June under other-than-honorable conditions.

Felix’s defense attorney claimed that Hawez’s testimony is an effort to retaliate against the Marine Corps and questioned the Kurdish recruit’s credibility by saying he only told investigators that he had been ordered into a dryer after reading about another incident.

But Hawez countered that he didn’t report being put in the dryer because it did not feel it was a serious issue at the time.

Felix’s lead attorney argued that many of the accusations against Felix were actually carried out by Eldridge, who was also originally facing a general court-martial but who now will appear before a summary court-martial as part of a plea agreement.

Felix’s defense attorney, Navy Lt. Cmdr. Clay Bridges claims that Eldridge cut a sweet deal with prosecutors to avoid a general court-martial. Even though a recruit initially said Eldridge had ordered him to get inside the dryer, Felix is being blamed. Now Eldridge faces a maximum sentence that is less than nonjudicial punishment — all for agreeing to say Felix is the bogeyman, the defense attorney said.

“A drowning man will grasp at straws,” Bridges said. “Sgt. Eldridge is surely that.”

Another former drill instructor, former Staff Sgt. Aaron Galipeau, told jurors on Nov. 1 that he was there when Felix and Eldridge ordered recruits to get into the dryer room, but Galipeau did not see any recruits get inside a dryer while he was there.

Galipeau was also accused of abusing recruits but he reached a pretrial agreement with prosecutors and was not charged.

Galipeau testified that on the night of the dryer room incident, he, Felix and Eldridge spent about two hours drinking Fireball Cinnamon Whisky that Felix had brought from his locker.

When they returned to the barracks, Felix and Eldridge ordered all of the recruits to run into the dryer room and do pushups and squats, said Galipeau, who called the episode “chaotic” and “unwarranted.” He also confirmed that Galipeau and the other drill instructors walked on top of the recruits because they were squeezed into such a small space.

He said he didn’t report it because he did not want to get punished.

“I knew I’d be sitting in this chair if I did report it,” Galipeau said. “No matter how you look at it, someone would have to pay for what happened.”

‘Developmental exercise’

Hawez said Felix often made him to do burpees, pushups and other incentive training as punishment for the smallest mistakes. Recruits are not supposed to do incentive training for more than 15 minutes, but on one occasion Felix made him exercise for 90 minutes, Hawez said.

Felix’s defense attorney raised the possibility that some of the allegations that he illegally incentive trained recruits could be explained as “developmental exercise,” which does not have time limits and can be done in the squad bay.

But Marine Maj. Meghan Kennerly, who investigated Felix for alleged abuse prior to Siddiqui’s death, said that drill instructors have all of their recruits do developmental exercises, not just one recruit. Other incidents in which Felix allegedly made recruits do high knees and other exercises in the dryer or shower rooms rise to the level of unauthorized incentive training, she said.

“No allegations could be justified as developmental exercise,” said Kennerly, who was serving as executive officer of the 4th Recruit Training Battalion at Parris Island in 2015 when she conducted a command investigation.

‘Where’s the terrorist?’

Another Muslim recruit that Felix is accused of targeting for abuse was Lance Cpl. Ameer Bourmeche,

Bourmeche testified that on July 24, 2015, he was awakened by Felix and Eldridge calling out: “Where’s the terrorist? Where’s the terrorist?”

Felix elbowed Bourmeche in the chin as the two drill instructors took him to the shower, where they ordered him to exercise with the water running until he was soaking wet, he said.

“They told me that I couldn’t go to sleep wet — that they needed to dry me off,” Bourmeche testified.

The three went into the dryer room and one of the drill instructors said he was paid “to weed out the motherf***ers like me,” Bourmeche said. He doesn’t remember who told him to get in the dryer, but he soon climbed inside.

“They asked me if I was affiliated with 9/11,” Bourmeche said. Then the dryer door closed and it was turned on. After about five seconds, he felt the heat. “I was tumbling in there,” he said.

After 20 to 30 seconds, one of the drill instructors opened the door and asked if he was still a Muslim, Bourmeche said. When he answered yes, the door was closed and the dryer was turned on again.

At that moment, Bourmeche lost all trust for his fellow Marines and thought “I joined the wrong Corps,” he said.

Once again, the dryer door opened and Bourmeche was asked if he still believed in Islam, he said. Again, the dryer was turned back on after he said yes. He said the drill instructors only allowed him out of the dryer after he said he was not a Muslim.

It was not the last time Bourmeche was allegedly targeted for being Muslim, he said. On another night during Marine Week, Felix tied Bourmeche to another recruit using belts and then made him simulate chopping off the Marine’s head while yelling “Allahu akbar,” he said.

Later that night, Felix told Bourmeche that he had been “fighting motherf***ers like me” for his entire career in the Corps and he wanted to mount the heads of Bourmeche’s family on pikes, Bourmeche said.

Bourmeche explained that he initially did not report any of the abuse because: “I just wanted to get out of there. I did not trust anyone there.”

Bridges pointed out that when Bourmeche told investigators about the dryer incident in October 2015, he said Eldridge was the one who kept asking him if he was Muslim.

The defense attorney also disputed Bourmeche’s account of the dryer turned on for up to 30 seconds each time. He said he plans to call expert witnesses, who will testify that the temperature inside the dryer would have reached 300 degrees Fahrenheit within seconds, yet Bourmeche did not suffer any visible burns.

The prosecution countered by asking Bourmeche if he was looking at a time piece to accurately gauge how long the dryer was turned on each time. He said no.

‘Get up you p***y’

While the death of Siddiqui is not a direct issue in Felix’s trial, attorneys on both sides sought to explain Felix’s actions and painted two distinctly different accounts of Felix and how he treated Siddiqui.

The defense attorney said Felix actually was not pushing Siddiqui as hard as the other recruits. He initially declined to elaborate on how or why Felix was supposedly going easy on Siddiqui, telling reporters in at Camp Lejeune: “That will play out in the evidence.”

When Siddiqui collapsed, moments before his death, Bridges said that Felix ran over to Siddiqui and asked: “Are you OK? Get up.”

Felix tried to revive Siddiqui by shaking him and then rubbing his fist on Siddiqui’s sternum, Bridge said.

“At that point, fear and instinct kick in,” Bridges said. “Are you OK? Slap. Are you OK? Slap. It’s not maltreatment.”

Many of the allegations that Felix slapped and punched recruits have been conflated by gossip and rumor, said Bridges, who argued that the prosecution’s case is rife with contradictory statements from witnesses.

The Corps’ prosecutor, however, said when Siddiqui collapsed to the floor, witnesses heard Felix tell him, “Get up you p***y; I know you’re faking it!”

Felix rubbed his fist on Siddiqui’s sternum and then slapped him in the face, according to his charge sheet.

Felix’s command

A total of 20 Parris Island personnel have been disciplined in the wake of TECOM investigations into allegations of abuse against recruits and junior drill instructors. Felix is one of seven Marines who have been referred to a court-martial.

Lt. Col. Joshua Kissoon is the highest ranking of those seven Marines. His general court-martial is set to begin in March.

Kissoon was fired as commander of the 3rd Recruit Training Battalion on March 31, 2016 and subsequently charged for his role in events that led to Felix returning to drill instructor duty while still under investigation for the Bourmeche incident.

Col. Paul Cucinotta, commander of the Recruit Training Regiment in March 2016, was surprised that Felix had been returned to duty as Siddiqui’s senior drill instructor. At Kissoon’s Article 32 hearing in June, Cucinotta testified that he asked Kissoon why they had not adhered to the order keeping Felix off the job.

“Had we talked about it,” Kissoon replied, “I would have tried to convince you to let him go back,” Cucinotta said at the hearing.