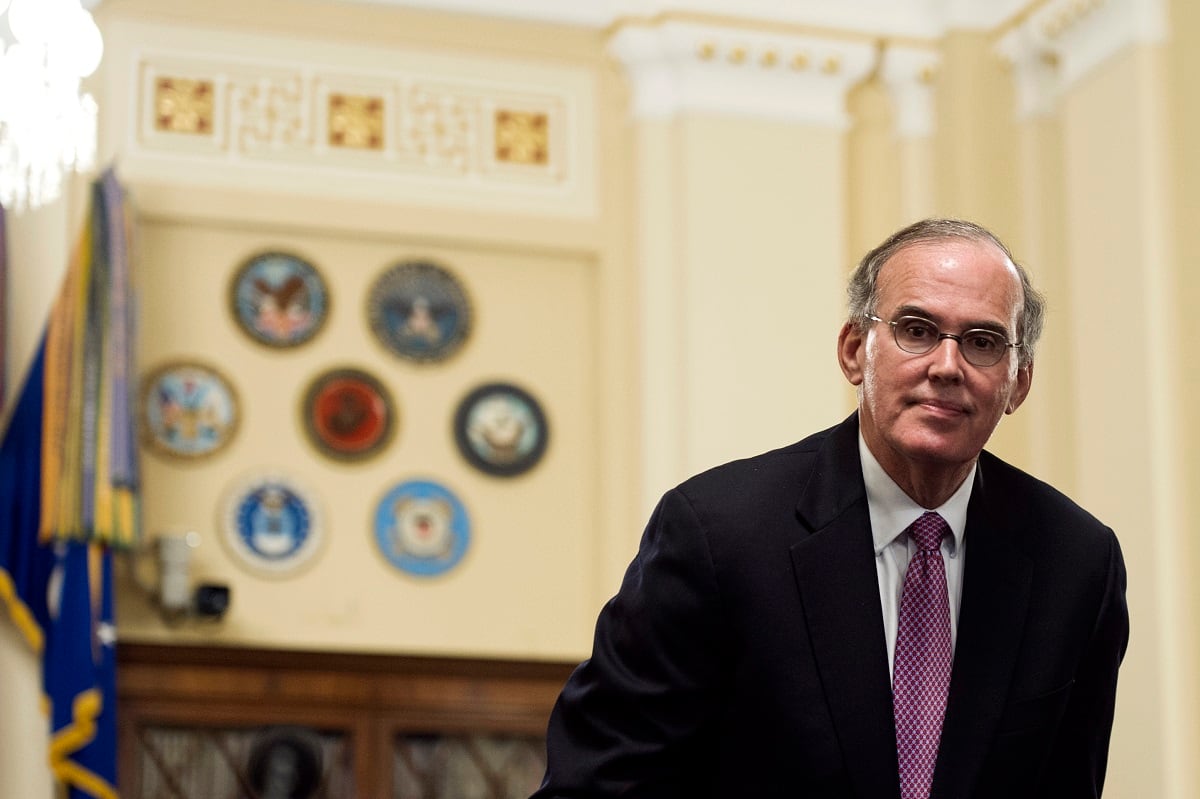

Talk to anyone about Peter Awn and they’re guaranteed to mention two things.

They’ll bring up what an impeccable dresser he was, particularly his collection of brightly colored socks. His wardrobe was “indicative of the curious personality that man embraced,” said Jared Lyon, president and CEO of Student Veterans of America.

More importantly, Awn was known as a staunch ally of veterans in the Ivy Leagues and was, as Lyon put it, “an institution as it pertains to student veterans’ success.”

Awn died in February from injuries related to a car crash, after serving 20 years as dean of Columbia University’s School of General Studies. During his tenure, the number of veterans attending Columbia skyrocketed.

“From the first moment Peter and I started discussing specifically recruiting student veterans, he was supportive on day one,” said Curtis Rodgers, Awn’s vice dean at the School of General Studies. “That evolved over time into thinking about what it truly means to serve student veterans … and ultimately what we could do as a university even beyond the classroom.”

Columbia had 40 to 50 veterans enrolled before Awn showed up, said Rodgers. Today, the school has 533 students attending using the Post-9/11 GI Bill, a group that can include veterans as well as their dependents. For context, Columbia enrolled more than 2,100 total undergraduate students in its School of General Studies during the 2017-18 academic year, according to a university representative.

Meanwhile, most other Ivy League schools have fewer than 100 Post-9/11 GI Bill users enrolled, Education Department data shows.

One of Awn’s lasting legacies will be his role in establishing Columbia’s Center for Veteran Transition and Integration, which takes programming for veterans built within Columbia and makes it available nationally.

“He was an amazing person and leader and what he allowed us as a team and school to do is return to what we were in our founding principles, and he gave us all the capacity to be the destination in the Ivy League for veteran undergraduates,” Rodgers said.

Crosby Kisler, a former Army ranger who is now a Columbia junior majoring in religious studies, spoke glowingly of Awn’s contributions to veterans education.

“It was apparent right away that he was dedicated to our community specifically,” he said. “He focused a lot on the veteran population.”

Kisler is also the president of Columbia’s MilVets chapter, a student group dedicated to promoting camaraderie among the campus’ veterans. He said that Awn would frequently make visits to the group’s lounge in the School of General Studies, which “was like a rock star walking into the building.”

In addition to being well-liked and respected by student veterans, Kisler said that Awn also did a lot to dispel the notion that veterans couldn’t succeed in the Ivy Leagues.

“He was one person who looked at that bias and rejected it summarily,” Kisler said. “He said, no, veterans do have a place in this university, and we do have things we can provide to higher education. And what better a place to do it than Columbia University?”

Columbia’s efforts to recruit veterans appear to have started a trend among Ivy League schools. Over the last five fiscal years, the number of Post-9/11 GI Bill users attending Ivy League universities has increased by 34 percent.

“[T]hey’ve done a tremendous job of increasing the awareness for high-performing student veterans that a highly selective school such as Columbia is indeed possible,” said Jim Selbe, an official with Service to School, a nonprofit dedicated to helping veterans get into the best schools they can.

Christine Schwartz, Service to School’s chief executive officer, said that universities like Columbia are showing veterans they have a chance to get into the Ivy Leagues. Giving them that confidence is half the battle, she said.

“If you have friends who are going to apply and have gotten in, then you’re more likely to,” Schwartz said. “If we have that narrative across not just all Ivy Leagues but also four-year colleges, it’s going to drive more veterans to apply.”

Fostering that belief among veterans was one of Awn’s greatest accomplishments. Just the fact that someone of his stature seemed to show any interest at all in veterans separated him from some of his peers in academia.

“Here was this accomplished academic who was a dean at an Ivy League school who seemed for the first time to be an academic who understood that veterans were an asset to campus, not liabilities,” said SVA’s Lyon.

Lyon met Awn during his time as a Florida State University undergraduate, after completing his Navy stint in 2005. It was one of Lyon’s first interactions with an academic where he “didn’t feel like the lesser person in the conversation.”

Awn should be considered the shining example of what a veteran-focused higher-education leader should look like, according to Lyon.

“If we want to move the needle forward, I think we should take Dean Awn’s example and bolster his legacy,” he said. “We can’t just be military friendly, but we also have to be military inclusive … to recruit that population and let them know they can achieve this.”