Cases of reported sexual assault in the military keep rising, but you wouldn’t think so if you look at how many suspected perpetrators actually end up being tried, much less punished for their alleged crimes. The services charged fewer suspected sexual assault perpetrators with crimes in 2022 than in the previous decade, according to data released Thursday in the Pentagon’s congressionally mandated annual sexual assault report.

While reported sexual assaults have increased over the past 10 years, and the percentage of substantiated reports has remained relatively stable, the number of cases prosecuted has been cut nearly in half.

Those numbers of prosecutions have continued to fall even as lawmakers and rights advocates pushed to take the power of prosecution out of the hands of individual military commanders, and hand it to an independent sexual assault prosecutor’s office.

“That change was largely due to the perception that when a military commander makes these makes these prosecution decisions, that they are not expert attorneys in these cases,” Dr. Nate Galbreath, deputy director of DoD’s Sexual Assault and Prevention Office, told reporters Thursday. “In addition to that ... commanders have a difficult choice between believing victims allegation versus people that they might know in their unit.”

Over the past decades, investigators found probable cause to bring charges in the majority of sexual assault cases. Rates of reliability averaged roughly two-thirds, ranging from the highest, 76% of reported assaults substantiated by investigators in 2014, to the lowest of 62% cases in 2017.

What has changed significantly over that time is how commanders have elected to handle those reports. In 2012, 68% of substantiated investigations resulted in criminal charges. In 2022, just 37% of them did.

Conversely, the numbers of non-judicial and administrative punishments, including separations, have risen. In 2012, 18% of cases resulted in non-judicial punishment, versus 35% in 2022. For administrative action, the number has climbed from 15% to 28%.

One reason there are fewer prosecutions is that survivors don’t want to go through the second trauma of the trial process, Galbreath said. A third of substantiated sexual assault reports never see charges or punishment because the survivors declined to participate in prosecutions.

The military’s sexual assault response process weighs the input of survivors when a report is substantiated: those survivors may voice their preference to see their attackers receive a lesser, non-criminal punishment rather than having to face them in court.

“Our feedback from the leadership within the special victims counsel, and programs of the victim legal counsel, is that this is the voice of the victim being heard,” Galbreath said. “Their willingness to support administrative actions and discharges or non judicial punishments and less confrontational forms of accountability action is something that we’re seeing over and over.”

In 2022, out of 7,378 reports, 2,117 were recommended for command action, the data shows.

Galbreath acknowledged that the feedback from special victim advocates is anecdotal, and that his office does not drill down into each of those cases to ascertain whether the decisions were made based on the commander’s opinion or the survivor’s wishes, nor does it survey survivors on how they came to their decisions.

Small uptick in reports in 2022

Overall, the data shows that reports of sexual assault were up about 1% last year across the services, a bit of a leveling off after the previous year’s report saw a 15% jump over 2020.

RELATED

Much of that can be attributed to the Army’s fluctuating numbers. The service’s reports spiked 25% between 2020 and 2021, but fell 9% between 2021 and 2022. That is contrasted with increases in the other services: 9% in the Navy, 3.6% in the Marine Corps and 13% in the Air Force and Space Force, whose numbers are reported together.

The 2022 data does not include a prevalence estimate, which is calculated from the biennial Workplace and Gender Relations Survey of Military Members. There, participants have the opportunity to detail incidents of unwanted sexual contact that were not officially reported. DoD then uses those responses to estimate how many people were actually assaulted in a given year, versus how many chose to report.

“Unfortunately, this report provides far from a complete picture of the military’s handling of the scourge of sexual assault,” Josh Connolly, vice chair of Protect our Defenders, said in a statement released Thursday.

The most recent data showed a massive spike between 2018 and 2021 ― the scheduled 2020 survey was delayed by the COVID-19 pandemic ― jumping from 20,500 estimated incidents to 35,900, an increase of 75%.

Accordingly, DoD estimated that reporting dropped from 30% to 20% over that time period.

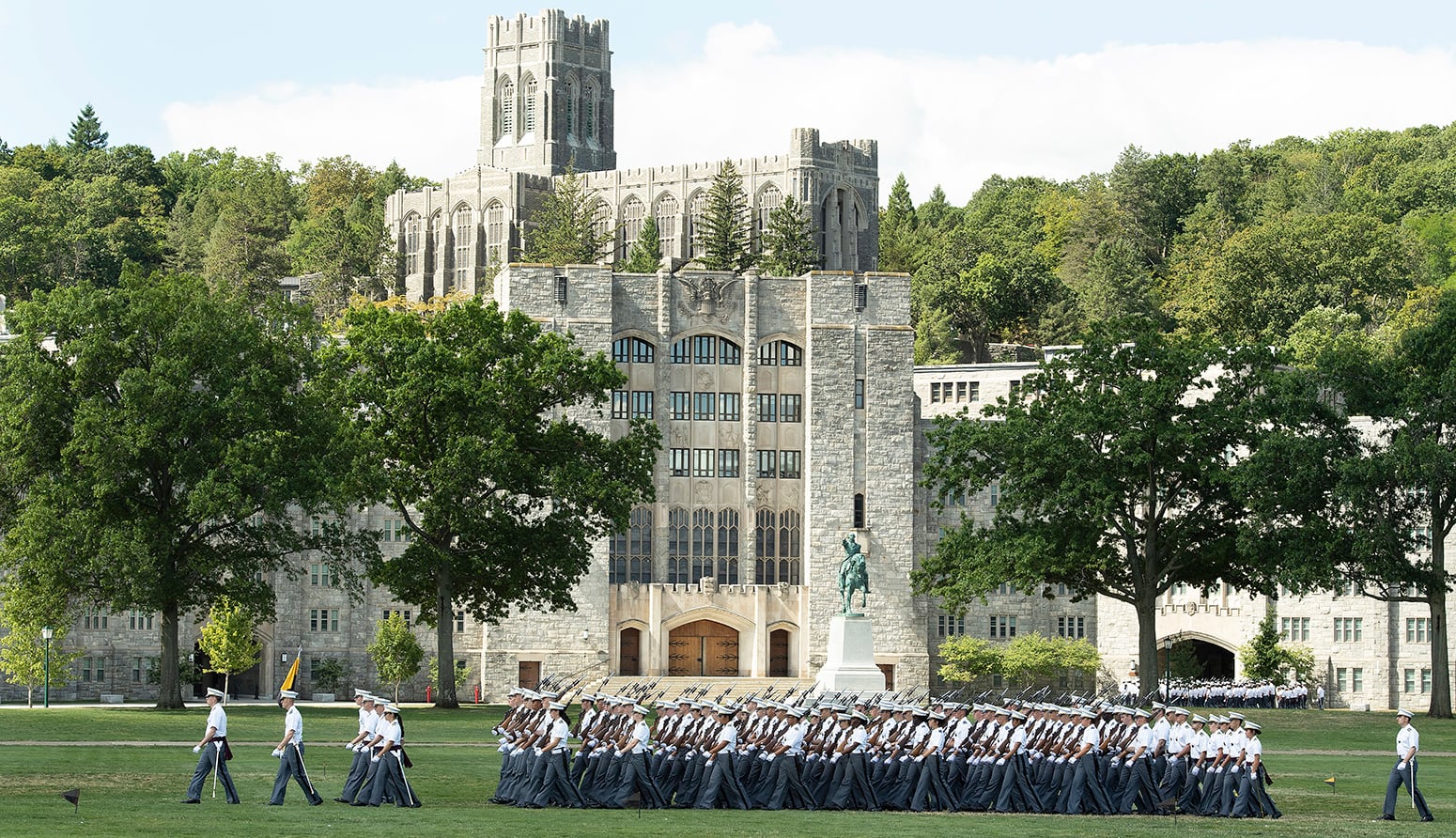

Connolly pointed to the military service academy sexual assault annual report released in March, which saw a 20% average rise in estimated incidents across West Point, the Naval Academy and the Air Force Academy.

The Pentagon is optimistic that more than 80 recommendations it’s implementing from a 2021 independent review commission on sexual assault will have an impact on its sexual assault problem. That includes the new independent prosecutor’s office, as well as replacing uniformed, part-time sexual assault response coordinators with full-time civilian professionals, and updating officer evaluation reports to include a description of that leader’s demonstration of commitment to sexual assault prevention.

Connolly called on Congress to step up its oversight of the recommendations’ implementation.

“We also need to take a serious look at the culture on our bases,” he added. “Deeply troubling tragedies continue to emerge from bases like Fort Hood and relying on the military’s assessment isn’t good enough. We must have expert third parties do a wholesale review of what is really happening.”

Beth Foster, head of DoD’s Office of Force Resiliency issued a call-out to troops to make sure that administrative efforts to improve prevention and response programs aren’t wasted.

“We can only do so much at the headquarters level,” she said. “Really, this is on our commanders, on our [noncommissioned officers] our frontline leaders to make sure that they are that they’re addressing this problem,” she said.

Meghann Myers is the Pentagon bureau chief at Military Times. She covers operations, policy, personnel, leadership and other issues affecting service members.