It’s military camouflage patterns all over again.

In a recent brief to a Defense Department advisory committee, fitness experts for each of the military services described how they’re on track to eliminate the inaccuracies in body-fat measurement methods that have frustrated service members with nonstandard builds for decades.

But this quest for accuracy has led them to distinctly different conclusions: No two services can even agree on where to measure a service member’s waist when deploying the hated, but hard-to-eliminate tape test.

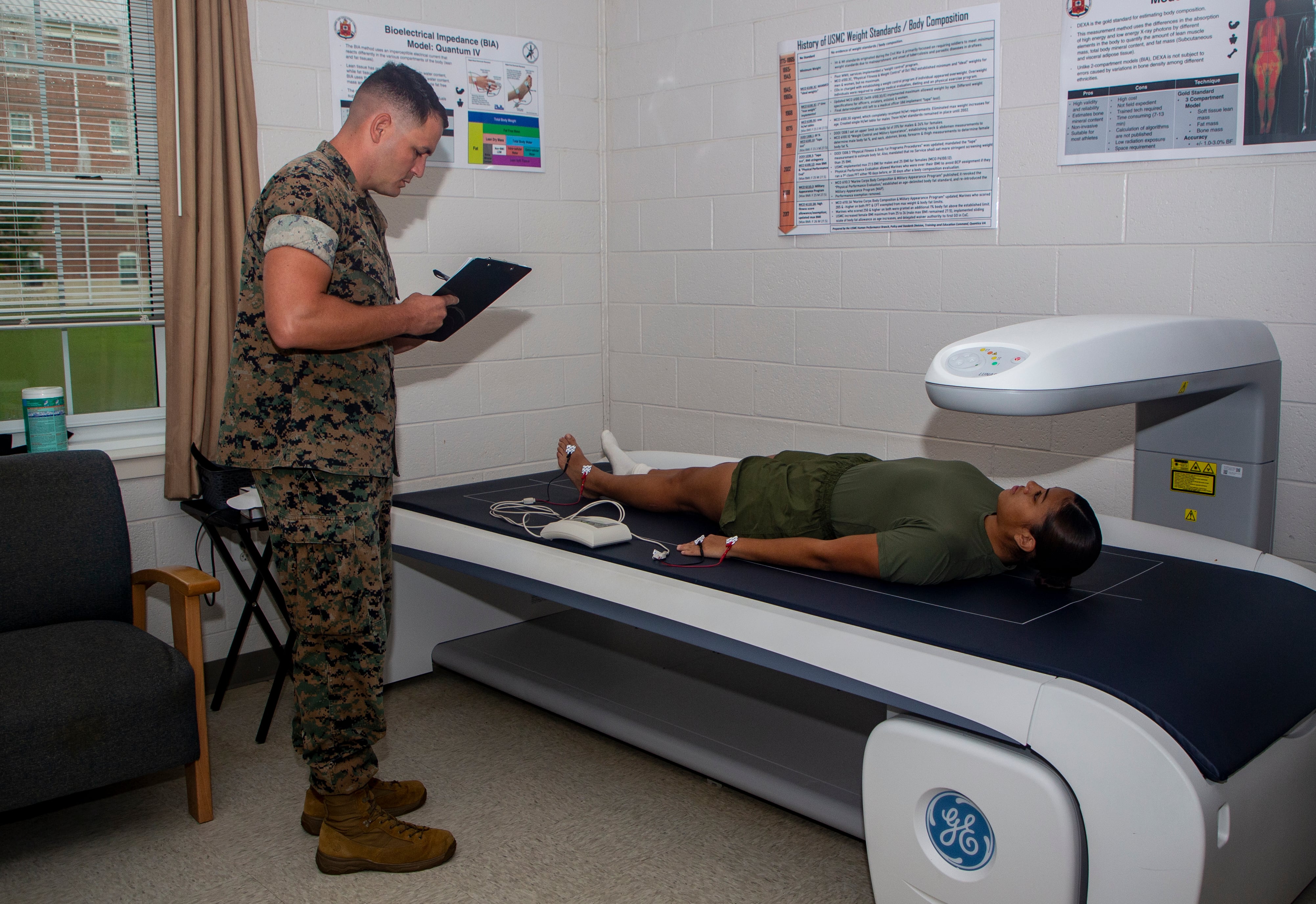

The good news is multiple branches are investing in the same high-tech fat-measurement equipment that officials say will be the final word on whether troops fall outside standards for troops approved to use it.

RELATED

With a Defense Department-wide pause on fitness testing during the COVID-19 pandemic, each of the services has had the chance to evaluate its methods and make changes. The DoD requires each service to conduct a body composition assessment, but existing measurement-based methods are error-prone, particularly for women.

A recent Marine Corps study found that .6% of male Marines and 6.3% of female Marines were incorrectly measured under the service’s existing tape test.

The Army, which has worked for years to refine and roll out its new Army Combat Fitness Test, announced in June that in 2024 it will do away with its old tape test, which measured men at the waist and neck, and women at the waist, neck and widest part of the hips, in favor of a single-site measurement for both genders at the waist.

If a soldier is out of standards in both height and weight screening and waist measurement, he or she can seek a commander’s approval to get scanned via the state-of-the-art DEXA, InBody 770, or Bod Pod methods.

The Marine Corps in 2022 made a similar change, requiring a bioelectrical impedance analysis of body fat, such as that provided by the InBody 770, prior to kicking anyone out for being out of standards.

The service also increased the maximum body fat allowable for women by 1%, permitting anywhere from 27% to 30% body fat based on age. This change, officials said at the time, “optimizes the balance between health and performance” for women.

The tape test, however, continues to be required prior to the machine assessment for those found out of height and weight regulation, with three site measurements for women and two for men like the Army’s legacy test.

The Air Force also unveiled a new body fat assessment program for airmen and Guardians in 2023, actually bringing back a tape test that assesses only waist-to-height ratio, after shutting down the old waist-measurement tape test in 2020. A more comprehensive new program is still forthcoming.

Meanwhile, the Navy is halfway through a two-year study of its body-fat analysis methods, continuing for now to measure men at the neck and waist, and women at the neck, waist and hips. It stopped administratively separating sailors for physical fitness test failures in 2017, and expects to announce changes to its program after the study wraps up in 2024.

For now, though, every service has a waist-measurement element of body fat assessment, having independently determined that to be a meaningful indicator of health and fitness to fight. As the Air Force said upon bringing the measurement back, “Excess fat distribution in the abdominal region is associated with increased health risk.”

But what exactly is the abdominal region, and how do you measure it? Regardless of who you ask, they’ll tell you the other services have it a little bit wrong.

The Army’s new program mandates taping right at the belly button, or the umbilicus, to use the service’s preferred term.

The Navy tapes at the iliac crest, where the top of the hip bone can be felt.

The Marine Corps opts for the “natural waist,” between the belly button and the bottom end of the breast bone.

The Air Force takes the midpoint between the iliac crest and the bottom of the ribs, providing a detailed anatomical chart showing musculature to help assessors find the right spot.

“Finding the umbilicus is typically a fairly easy thing,” versus something like the iliac crest, Michael McGurk, director of research for the Army’s Center for Initial Military Training, told the Defense Advisory Committee on Women in the Services at its June meeting. “We’re already ready, there’s going to be some question someplace where we’re going to have somebody that doesn’t have an umbilicus because of surgery or something, but we’ll figure out how to adjust for that.”

Col. Kevin Baldovich, chief of integrated operational support at the Air Force Medical Agency, said he was concerned about variability with the Army measurement: What if the belly button pointed down or otherwise thwarted accurate measurement?

His slide presentation also took issue with the multisite measurements the Marine Corps and Navy continue to use, saying they have less correlation to abdominal obesity and a relatively large potential for error. After assessing many studies with varying conclusions, he said, “we had to define a landmark.”

The Navy and the Marine Corps, which historically have beefed over fitness testing methodology, refer in part to the same 1980s studies on body fat, but end up with different conclusions about where to measure. In presentation briefing slides, Navy Lt. Geoffrey Ciarlone, a service physiologist, said the Navy referred to National Institutes of Health guidance in choosing the iliac crest as its measuring spot.

“As the largest service, we like to lead the way,” McGurk said of the Army approach. “And we do talk with our sister services all the time. Sometimes talks are more productive than others. But I think that we’re generally in the right area.”

Apart from the services’ determination to find unique ways to solve identical problems, the brief also revealed the difficulty of getting away from some manner of tape test, which troops and experts have long criticized as inaccurate.

It’s so cheap and efficient to take circumference with a tape measure that the relative accuracy it provides has long been assessed as a reasonable tradeoff in lieu of buying bioelectrical impedance analysis scanners at $21,000 apiece for every base. While some studies continue and more changes may be forthcoming, officials hope making the best-in-class scanners available to the small percentage of troops who require them will be an acceptable solution.

Concerns already have arisen that service members requiring access to the scanners might not be able, or permitted, to travel to a location that has one.

But “in a rare show of service cooperation,” McGurk said, the Army and the Marine Corps are investing in the same model: the InBody 770.

The Army plans to buy 500–600 of the machines, and the Marines reportedly are purchasing more than 250. For those who don’t regularly visit a military installation, such as members of the Reserve Officer Training Corps, McGurk said, any body fat-measuring machine “under government control,” including those at state-owned universities, may be used to meet the requirement.

“We think with that, plus the ones we’re giving to our National Guard and Reserve, they’ll be widely, widely available,” he said.

Hope Hodge Seck is an award-winning investigative and enterprise reporter covering the U.S. military and national defense. The former managing editor of Military.com, her work has also appeared in the Washington Post, Politico Magazine, USA Today and Popular Mechanics.