It was a few minutes before 6 a.m. and still very dark on January 6, 1942, when the control tower at New York’s LaGuardia Airport received a radio message: “Pan Am Pacific Clipper, inbound from Auckland, New Zealand. Capt. Ford reporting. Due arrive Marine Air Terminal LaGuardia seven minutes.”

The tower quickly checked with Pan American Airways operations. There was no flight plan for a Pan Am flying boat to arrive at that time—certainly not one from as far away as New Zealand. World War II had begun for America a month before.

Was this a joke? Could it be a German crew flying an American plane?

Weather reports were being coded—might this be a coded message that the control tower couldn’t decipher?

Since it was still dark, no one could spot the plane from the airport. Seaplane night landings were forbidden in Bowery Bay, so the Pacific Clipper was instructed to circle and wait for sunrise. While Capt. Robert Ford orbited the New York area, Pan Am officials and military personnel were alerted and rushed to LaGuardia’s Marine Air Terminal building.

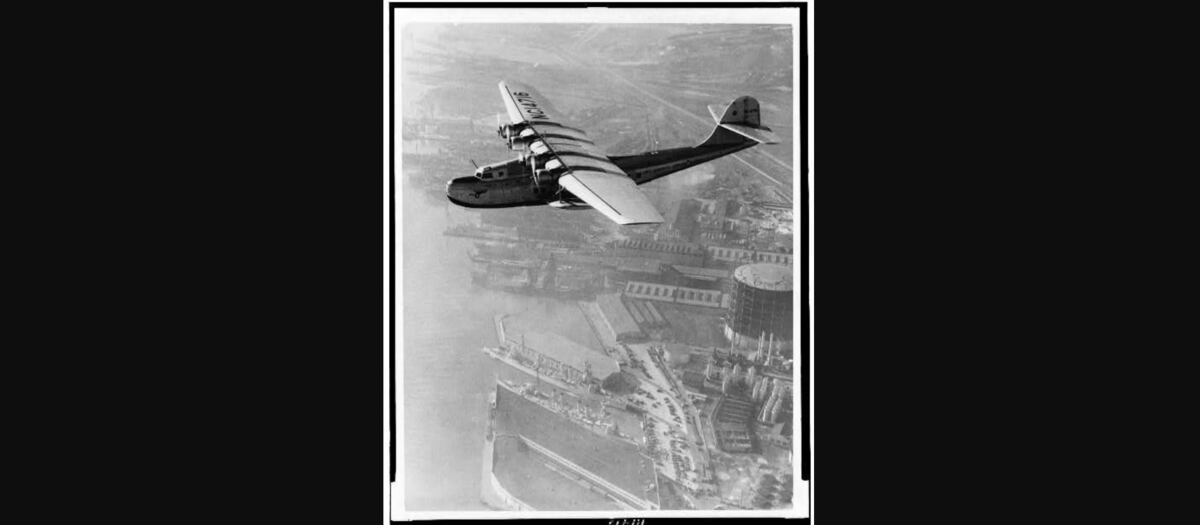

The giant Boeing B-314 landed a little after 7 a.m., completing the longest continuous—and most unusual— flight of a commercial aircraft during the early days of American involvement in WWII. More significant at the time, it was the first vessel of any kind to reach the United States from the Pacific war zone.

Once the flying boat was moored, Ford and his 10-man crew and three Pan Am employee-passengers, dressed in summer clothing and clutching blankets to ward off the chilly wind, were quickly moved inside the terminal. After hot coffee and a quick breakfast, crew members as well as passengers were interviewed by military intelligence personnel.

Newspaper reporters seeking information about the unusual arrival were given only the bare facts for security reasons. They were told the Pacific Clipper, operating in the Pacific between California and New Zealand, had been forced to deviate from its original flight plan and return from New Zealand by continuing westward because of the December 7, 1941, attack by Japanese naval air forces on Pearl Harbor.

The landing at New York marked the end of a nearly complete round-the-world flight of more than 31,500 miles.

The Pacific Clipper’s trip from San Francisco and Hawaii to Noumea, New Caledonia, had been routine until two hours after its departure from Noumea on December 8 (it was still December 7 in Hawaii).

First radio operator John D. Poindexter, taking down Morse code dispatches, heard the first reports about the carrier strike on Pearl Harbor. Then came a simple two-word message: “Plan A.” This was a prearranged signal that meant all Pan Am aircraft in flight were to maintain radio silence, land at their next scheduled destination and await instructions.

“It seemed incredible that the news could be true,” Homans K. “Swede” Rothe, the first engineering officer, recalled later. “It might have been a mistake or maybe only a test.”

It was neither. Capt. Ford reached in his flight bag for the sealed emergency orders that all Pan Am captains had begun carrying when the political situation started to deteriorate in the Far East. He immediately briefed the crew that the airline would now be operating on a wartime basis and they would continue to Auckland, New Zealand.

The Pacific Clipper was one of three Pan Am Clippers airborne over the Pacific at the time of the attack. Another B-314, the Anzac Clipper, with Capt. H. Lanier Turner in command, was flying with a crew of 10 and 17 passengers from San Francisco to Hawaii, the first leg of a 14-day round trip to Singapore, and was within about 40 minutes of a scheduled landing at Pearl Harbor that morning.

It had been an uneventful flight of about 15 hours when Radio Officer W.H. Bell informed Turner about the bombing and confirmed the attackers were Japanese. A landing there was now out of the question.

Turner immediately pulled out his sealed envelope. The instructions were clear: Get the aircraft to a safe harbor as quickly as possible, offload the passengers and camouflage the aircraft. Turner decided to land at Hilo on the Big Island of Hawaii, which had a protected harbor and was farthest from Pearl Harbor.

Turner quickly briefed the passengers on the news. Once he landed and told the passengers they could go to local hotels, he announced that he was going to refuel and return as soon as possible to San Francisco.

Not a single passenger wanted to make the return flight; all decided to take their chances and make their way to Honolulu any way they could. After the plane was refueled, Turner and crew took off that night and flew the Anzac Clipper the 2,400 miles back to Pan Am’s base on Treasure Island at San Francisco.

The Philippine Clipper, a Martin M-130 under the command of Capt. John H. Hamilton, was en route from Wake Island to Guam when the radio operator received the news from Pearl Harbor.

A few minutes later, a message followed from Commander W. Scott Cunningham, the naval officer in charge on Wake, requesting that the plane return and prepare to make a long-range reconnaissance flight to search for the Japanese task force because the M-130 could fly farther out than his fighters could go.

Hamilton immediately reversed course and ordered the crew to dump about 3,000 pounds of gasoline, to get down to the landing weight of 48,000 pounds.

After the Clipper landed at Wake, it was quickly refueled and was preparing to make the patrol flight before escaping to Midway.

Just before noon, a formation of 36 Japanese bombers attacked. Within 10 minutes the area was a shambles. Pan Am’s terminal and other facilities were destroyed and nine Pan Am employees were killed.

The Clipper, floating helplessly in the lagoon, was strafed and riddled with 97 bullet holes “right up the fuselage without hitting a single vulnerable spot,” according to one report.

As soon as the attackers left, Capt. Hamilton, a lieutenant in the Naval Air Reserve, loaded 70 American civilian passengers and Pan Am employees, one of them wounded, and headed for Midway without making the reconnaissance flight.

Although it had been stripped of all extraneous equipment and cargo, the M-130 was still overloaded and barely airworthy. Hamilton made two unsuccessful takeoff attempts before the Clipper finally became airborne.

He headed to Midway, a flight of 1,185 miles. About 40 miles from a landing at Pan Am’s blacked-out base there, Hamilton reported he saw two warships heading away from Midway and learned that the atoll had been shelled that afternoon.

The Clipper was refueled and the next day headed for Pearl Harbor, which was reported safe for landing. On December 10, he flew the Philippine Clipper under radio silence to Pan Am’s base on Treasure Island.

On December 8, six hours after the Pearl Harbor attack, Japanese aircraft dived on Hong Kong’s Kai Tak Airport and harbor, where Pan Am’s Hong Kong Clipper, a Sikorsky S-42 with Capt. Fred S. Ralph in command, was being readied for an early morning departure to Manila on its regular schedule between the two cities.

It was set on fire by incendiary bullets and burned to the water’s edge—Pan Am’s only Clipper casualty of the war due to enemy action.

All of Pan Am’s bases in the Pacific suffered heavy losses during this brief period. In addition to the nine employees killed, 81 were captured and millions of dollars of equipment and facilities were destroyed.

While all this bad news was being received in Auckland, Capt. Ford and his crew waited there for instructions that were to come through the American embassy. The word finally came on December 15. Ford was directed to return to the United States by any route that would avoid enemy interception, no matter how long it took.

He and his crew would have to plot their own route, proceed without accurate charts, navigational aids or weather forecasts, land in unfamiliar harbors and locate fuel sources. From that time on, no one at Pan Am headquarters would know exactly where the Pacific Clipper was until it reported to LaGuardia tower.

“We had begun a camouflage job on the Clipper,” John D. Steers, fourth officer on the plane, recalled, “and only half the American flag had been removed when the urgent message was received to disassemble two [spare] engines and load them. We were to return to Noumea, Caledonia, pick up 22 Pan Am employees, women, and children, and take them to Gladstone, Australia. We were then to proceed westward to New York. The engines were to be left as spares, one each at Karachi, India, and Bahrain, an island off the coast of Saudi Arabia.”

From Noumea they headed to Gladstone, the first flight ever made between the two locations, then on to Port Darwin.

Besides the crew, three Pan Am employees remained on board: a meteorologist from Honolulu who had been assigned to the Auckland base, an airport manager from a Middle Eastern port and a radio operator from Noumea.

The route was not yet in a declared war zone, but as yet no one knew how far south the Japanese had actually pushed. However, the flight continued under complete radio silence to Surabaya, Java, in the Netherlands East Indies.

Ford intended to stop only for fuel because, as Steers said, Java was by then “definitely a war zone.”

“The American consul in Port Darwin was to have notified Surabaya of our coming,” Steers explained. “We had arranged to answer challenges from Surabaya on CW [continuous wave] frequencies. Our challenge was to be the letters B-E-A-M. Our answer was to be H-O-R-N. The Dutch never got the message from Port Darwin.”

The Clipper used British call letters as suggested by British Overseas Airways Corporation — BOAC — but there were no answering transmissions.

As the lumbering 140- mph Clipper approached the harbor at Surabaya, a patrolling snub-nosed Brewster F2A Buffalo fighter with British Royal Air Force markings got on its tail.

The pilot reported the sighting to his ground station. John Poindexter, the Clipper’s radio operator, picked up transmissions between the fighter pilot and controller and later reported the following conversation had taken place:

Controller: “What is she?”

Pilot: “I don’t know, but she’s a big one. Might be German or Japanese. Wait. There’s part of an American flag on her side.”

Controller: “That doesn’t mean anything. Anyone can paint on an American flag.”

Pilot: “Then you’d better send up some more help.”

Four more fighters were scrambled.

Controller: “Stay on her tail. If she gets even a little way off the normal course for landing, shoot her down.”

“We were told later that one of them remarked they’d better call the ground station before they opened fire,” Steers said. “One of them peeled off and drew up on our tail. He asked,‘Shall I let them have it?’ Then the ground station asked if we didn’t have some marks of identification. They hesitated and one of them came over the top. Then what remained of the U.S. flag was spotted by a fighter pilot.”

“They were still suspicious and followed us right into the bay,” Poindexter reported. “When we hit the water they sailed right over us and on into the airport. As we slowed down, a speedboat zigzagged out to our position. Capt. Ford put the Clipper in a tight turn to stop our forward progress. The boat approached and we were instructed by bullhorn to follow close behind to our mooring. Then the voice told us why: ‘The harbor is mined!’”

The Clipper had arrived in Java on December 18 and was detained while the military authorities contacted their headquarters in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) for permission to release it. Meanwhile, the 10 crew members were given inoculations against typhus and cholera, and several of them became quite ill.

The plane needed 100-octane fuel, but not enough was available, so automobile fuel had to be used.

Ford decided to depart as soon as their release was approved and took off early on December 21 for Trincomalee, Ceylon. The four engines, spitting and popping, let the crew know that they did not enjoy running on low octane gasoline.

The Clipper crew stayed there until December 24 and departed for Karachi, India (now Pakistan). An hour after takeoff, the studs on a cylinder head of the No. 3 engine snapped and Ford had to feather the engine.

He decided to return to Trincomalee, where engine repairs were made by “Swede” Rothe and John B. “Jocko” Parish, the Clipper’s flight engineers.

They fashioned a tool in the blacksmith shop of a British warship anchored in the harbor and attached the studs to complete the repair. Two days later, the Clipper flew across southern India to Karachi’s harbor.

Ford thought it best not to dally. After refueling and a night’s rest for the crew, the Clipper left for Bahrain, in the Persian Gulf on the eastern shore of Saudi Arabia.

Again, only automobile fuel was available, but Ford had to make do. He pushed on to a landing in the Nile River at Khartoum, Sudan’s capital city. Ford wanted to refuel quickly, but he received a “vital military affairs” message asking him to wait for unidentified VIP passengers who would arrive via BOAC.

“We waited for two days,” Steers reported. “The VIPs were the publisher of a Chicago newspaper, his wife and sister-in-law.”

However, the BOAC aircraft flying them from Cairo had to make a forced landing because of engine trouble. When the passengers didn’t show up, Capt. Ford was authorized to proceed without them.

On the takeoff from Khartoum on New Year’s Day for Leopoldville (later Kinshasa), in the Belgian Congo, one of the Clipper’s engines blew off an exhaust stack, which made it not only noisy but a fire hazard. But after landing at Leopoldville, with no exhaust parts available, Ford decided to take the risk.

He ordered a full load of more than 5,100 gallons of aviation fuel to make the long crossing of the South Atlantic to Natal, Brazil.

The takeoff was risky in the blistering heat. It took full engine power on the four Wright Cyclone 14-cylinder engines for a full three minutes to take off and climb.

The plane was on the edge of a stall, and Ford later reported that he found the overloaded condition made the aileron controls seem frozen when he tried to bank. He cautiously nursed the giant seaplane westward.

The 3,583-mile flight was completed in 23 1/2 hours, the longest nonstop flight by a Pan Am aircraft up to that time.

John Steers said that Second Officer Roderick N. Brown had constructed a Mercator projection of 10 degrees of latitude on a strip of paper.

“This served as our chart from Leopoldville to Natal,” he explained. “At night over water, we dropped flares and with our drift sight we checked drift and ground speed. During daylight we dropped smoke bombs.”

Steers continued: “We stayed at Natal about four hours, gassing and putting the exhaust stack that had blown off at Khartoum back together again. This time we put part of a Consolidated PBY Navy twin-engine flying boat part on it, wrapped a tin can around it, and wired the whole business with bailing wire. We left Natal on January 3 and headed for Port-of-Spain, Trinidad. The exhaust stack blew off during the takeoff from Natal so the engine hammered all the way to Trinidad.”

The B-314 made the final leg of the trip from the balmy Caribbean to freezing New York in 13 hours. The crew and three Pan Am passengers, all Californians, were exhausted and unprepared for the cold January weather when the Pacific Clipper touched down in the harbor off LaGuardia.

“The water splashed up on the sea wings and froze solid,” Steers recalled.“The hawser on the buoy was like a chunk of ice.”

After the crew members were questioned intensively about the trip by military intelligence officers, they learned from Pan Am officials that they and the plane were being transferred to the Atlantic division and would not return to San Francisco to complete a full circumnavigation.

The flight of the Pacific Clipper had taken one month and four days after leaving San Francisco. It had touched down in the waters off five of the world’s seven continents, crossed three oceans and made 18 stops under the flags of 12 different nations and spent 209 1/2 hours in the air, the first plane to follow such a route.

And it had flown more than 6,000 miles over desert and jungle, where a forced landing would have been disastrous for a flying boat.

The flight had been made without adequate navigation charts over territory never before flown by Pan Am and without advance weather reports and information about possible landing sites.

And the crew never knew with any certainty whether they would be able to get fuel and maintenance supplies at any of the stops. They had proceeded under a radio blackout through and around the war zones.

Pan Am management decided to give the flight as much publicity as possible under wartime restrictions.

The January 1942 issue of New Horizons, the company magazine, boasted, “As a test of ingenuity, self-reliance, and resourcefulness, it proved sensationally that Pan American’s multiple crews, operating techniques, and technicians could meet any possible situation that might arise in long distance flying.”

The New York World Telegram described the flight as the “greatest achievement in the history of aviation since the Wright brothers flew at Kitty Hawk.”

An editorial in New York’s Herald Tribune stated: “The feat is one of which the pilot and crew and the Pan American World Airways may well be proud….Its significance will not be missed on either side of the Atlantic.”

Capt. Ford’s post-flight report praised his fellow crew members.

He also pointed out that “the underlying credit for success of the whole operation should, of course, be given to the training that all hands have received in the organization of routine methods of handling practically every exigency that can arise in the course of long flights. The standard interchange of pilots, navigators, meteorologists, communications experts, engine and airplane mechanics provided in the standard Clipper crew, gave us experts in every operation required. Every man simply fell into the routine for which he was trained and everything went like clockwork every mile of the way.”

The Pacific Clipper had nearly flown around the globe, but since it was not to return to its home base at San Francisco its flight was not officially considered a complete round-the-world flight.

While it was en route, most of the 314s had been transferred to the Navy, including the Honolulu, Yankee, Atlantic, Dixie and American Clippers.

The Army Air Forces retained the Capetown, Anzac and California and designated them as C-98s.

The remaining Boeing Clippers went to BOAC.

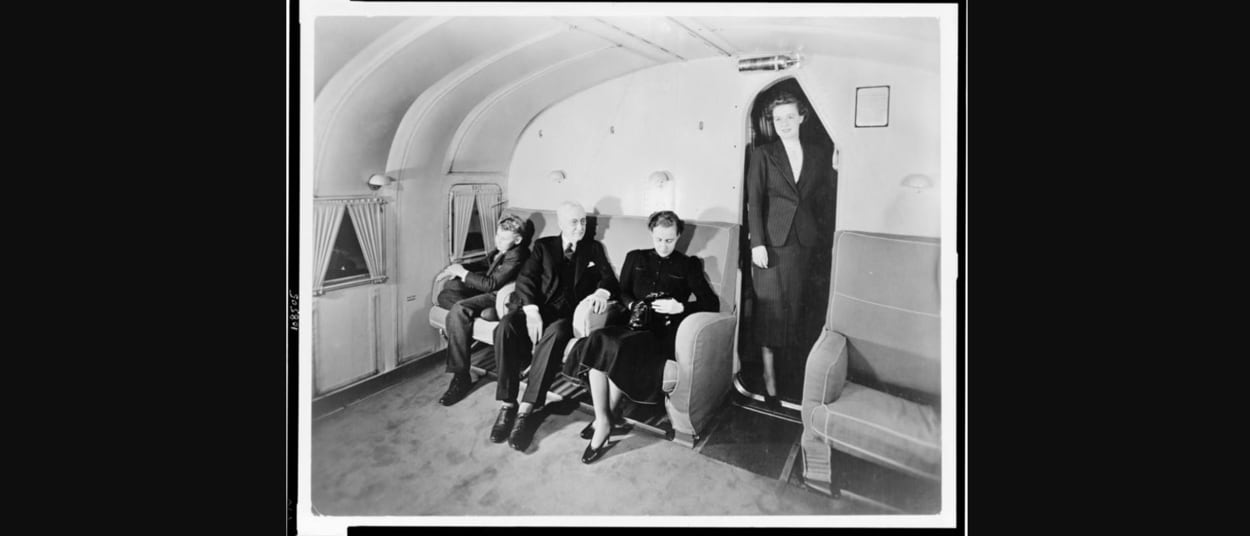

The Dixie Clipper made history in January 1943, when it flew President Franklin D. Roosevelt to Casablanca, Morocco, in accordance with orders specified in Special Mission 71.

Piloted by Capt. Howard M. Cone Jr., the B-314 carried President Roosevelt to a conference with Prime Minister Winston Churchill at which they decided to demand the unconditional surrender of Axis forces.

Afterward, it was the Anzac Clipper that finally became the first seaplane to completely circumnavigate the globe. But like the Pacific Clipper’s trip, the flight did not go as originally planned.

Capt. Charles S. “Chili” Vaughn flew the Anzac from New York to Bahrain on the Persian Gulf and turned the plane over to Capt. William M. Masland, who had arrived there in the Capetown Clipper.

Masland, flying in accordance with Special Mission 72, was to meet three secret passengers in Trincomalee, Ceylon, and transport them in the Anzac Clipper to Australia for a secret meeting with Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek.

But intelligence reports indicated that the Japanese might have learned of the meeting and the trip was canceled. However, Maj. Gen. Albert C. Wedemeyer and two members of his staff were then ordered to go to Perth, Australia, so Masland flew them there, where he picked up a Pan Am employee and 26 U.S. naval officers and was expected to return to New York the way he had come.

But Masland decided to continue eastward. He flew to Brisbane, New Caledonia, Fiji, Canton Island and Pearl Harbor to San Francisco, then to New York. The Anzac Clipper had thus completed an authentic globe-girdling flight of more than 30,000 miles, crossing the equator four times in the process.

On Christmas Eve 1945, 2 1/2 years after his history-making world flight, Masland landed a B-314 in Bowery Bay, the final landing of a Pan Am flying boat at its New York sea terminal.

He summarized the end of that flight in his memoirs, Through the Back Doors of the World in a Ship That Had Wings: “The night watchman met us, no one else. No flags, no bands, no speeches, just the night watchman making his usual rounds. There never was a quieter end to a brave and glorious era.”

Pan Am’s Clipper service in the Pacific ended a few weeks later on April 9, 1946, when a B-314, the American Clipper, landed at San Francisco.

Only one B-314 had been lost during World War II, though not due to enemy action.

That accident occurred when the pilot of the Yankee Clipper made a low turn too close to the water and the aircraft crashed in the Tagus River off Lisbon, Portugal, on February 22, 1943. Twenty-four people died, and well-known singer Jane Froman was badly injured. The cause of the accident was determined to be pilot error.

The remaining 314s, after being acquired by charter operators, were eventually salvaged for parts, scrapped or destroyed.

The rapid wartime advances made in long-range, land-based four-engine transports such as the Boeing 307 Stratoliner, Douglas DC-4 (C-54) Skymaster and Lockheed L-49 (C-69) Constellation helped contribute to the 314’s quick demise.

Of the dozen B-314s produced between 1938 and 1941, today none survive intact, but a few pieces of one aircraft are on display at the Museum of Flight in Seattle.

Photos and scale models of Pan Am’s Sikorsky, Martin and Boeing seaplanes on display in several museums around the world are all that remain to remind us of a fascinating period in aviation history.

This article was first published by one of Navy Times’ sister outlets, Aviation History Magazine. For additional reading, award-winning aviation author C.V. Glines recommends: Last of the Flying Clippers: The Boeing B-314 Story, by M.D. Klass; and Wings to the Orient, by Stan Cohen.