Despite a COVID-19 pandemic that has uprooted life for Americans inside and outside the military in 2020, the Navy still managed to graduate its largest class of recruits in 15 years last month, while exceeding its enlisted accession goals for fiscal 2020.

“Just think about that: Amidst COVID, the largest graduating class from (Recruit Training Command) since 2004,” Chief of Naval Personnel Vice Adm. John Nowell told reporters in October.

But left out of Big Navy proclamations is the fact that much of this success was borne on the backs of an unspecified number of Navy sailors who have been largely confined to an isolated U.S. Army base in Wisconsin, three hours from the Navy’s Great Lakes, Illinois, boot camp.

Sailors there are tasked with looking after recruits for their 14-day quarantine period before they board buses and commence a three-hour bus ride south to formally commence their basic training.

But for some sailors now stationed at McCoy — a third of whom were not already assigned to Recruit Training Command and were pulled in from elsewhere in the fleet — the assignment has been marked by uncertainty and, at times, weeks with no days off.

RELATED

One petty officer who contacted Navy Times questioned the setup at McCoy last month, and why Big Navy feels the need to ship recruits at a level that appears heedless of the pandemic raging across the country.

The petty officer, who asked to remain anonymous for fear of repercussions for speaking out, worked as a barracks supervisor and was forced to live in the same bay where the recruits wait out their isolation period.

“A lot of people are doing four weeks straight of being a barracks supe with no days off,” the petty officer said. “To work for four weeks straight, for anyone, with no full day off is slightly ridiculous.”

Ridiculous even for a Navy sailor with years of experience.

“I’m a petty officer,” the sailor said. “I’m used to being s--- on my whole career.”

While such supervisors have their own room, they use the same head as the recruits and often don’t get any days off during their rotation, said the sailor.

Those barracks supervisors are relieved by a “floater” who provides breaks each day, but the petty officer said supervisors can only get four to six hours off at a time because that floater then needs to go spell another supervisor.

The petty officer said that when one group ships, another often comes in right behind them:

“You get them [outgoing recruits] on the bus, 1 or 2 in the morning, your next batch of recruits comes in the next morning or two hours later.”

There are between 1,800 to 2,000 recruits at McCoy on any given week, officials said.

In the midst of a pandemic, the petty officer wondered why Big Navy is so focused on keeping up a relentless recruit processing pace that has roped in sailors not assigned to RTC and separated most McCoy sailors from their families in the process.

“As if COVID hasn’t happened,” the sailor said.

“Even if you cut back 20 to 30 percent of the recruits you ship for a week, you could ease up on some of this and people could get time off,” the petty officer said. “This stresses people out for the simple fact of no time off and not being able to see your family.”

The petty officer also said McCoy sailors are unsure of how long they will have to do the job, though non-RTC sailors brought in to help have received orders between six and 10 months.

The petty officer said they were given about a week’s notice to get to McCoy.

“You just don’t know how long this is going to go for,” the sailor said.

'Proud of their service’

Navy officials acknowledged the challenges sailors assigned to McCoy are enduring, but said that keeping the recruit pipeline flowing is essential.

The Navy began using McCoy as a quarantine site for new recruits in late August, ending a plan where recruits had been housed in 11 hotels closer to Great Lakes for two weeks before being tested and shipping out, according to CNP spokesman Cmdr. Dave Hecht.

Using McCoy saves the government more than $2.5 million monthly, he said in an email to Navy Times.

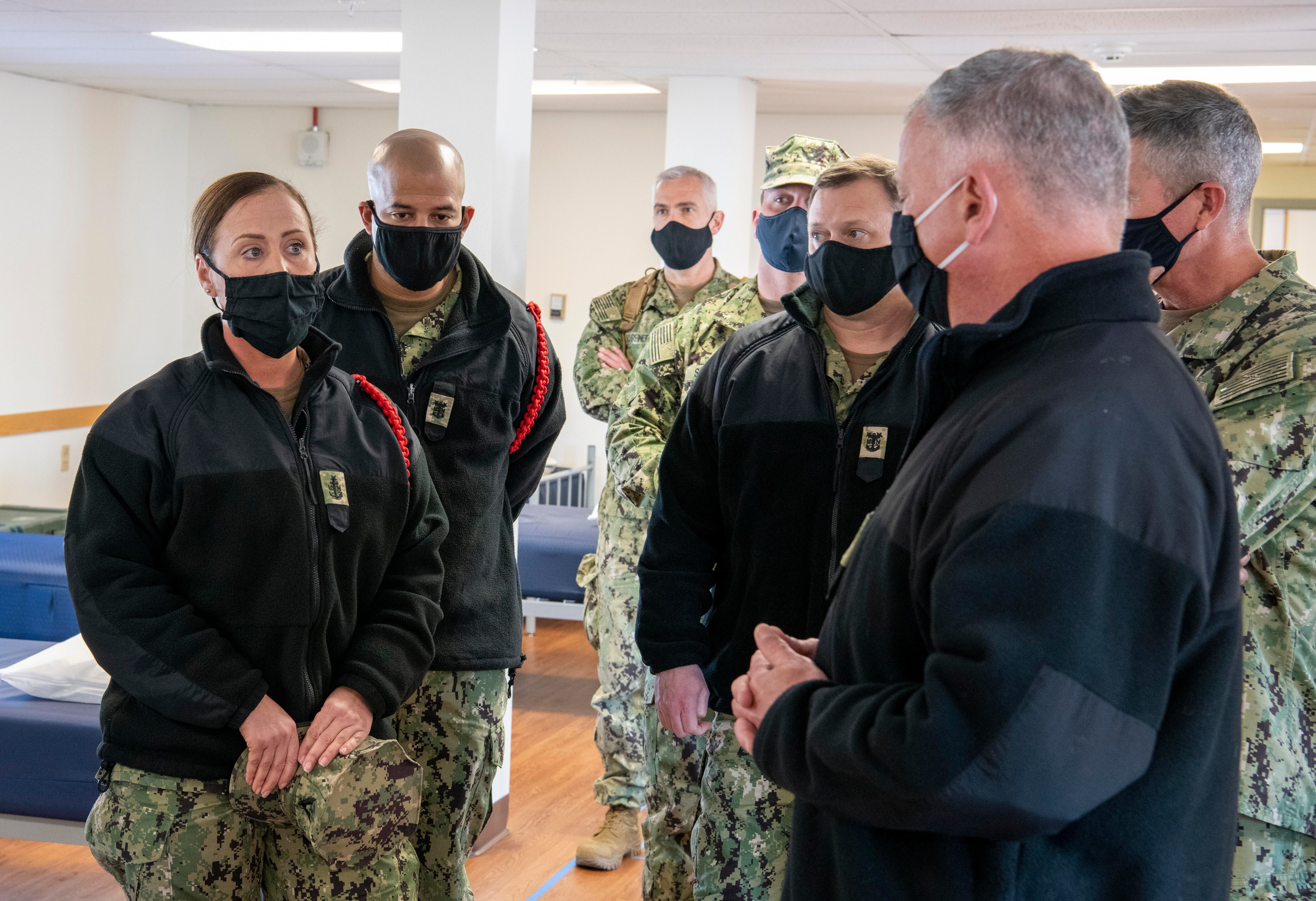

In a statement after visiting McCoy last week, CNP Nowell acknowledged that working at McCoy “is not an easy assignment.”

“But everyone I met understands that the use of Fort McCoy is for the health and safety of the force, and I couldn’t be more proud of their service and sacrifice,” Nowell said.

Despite the pandemic, the shipping pace must continue “in order to reduce gapped billets at sea,” Nowell said.

“Those gaps are a sure-fire way to stop the Navy from accomplishing its mission, and we cannot let that happen,” he added.

Nowell said he spoke with sailors “who had to leave their kids with family members” while assigned to McCoy, "but they remain passionate about the mission.

The petty officer said Nowell’s all-hands call at McCoy was the “same as most every all hands calls.”

“Not very much information put out and basically pointless,” the petty officer said.

While the Navy declined to say how many sailors are assigned to McCoy, Hecht said that about a third of the force is individual augmentees and intermediate stop sailors, pulled for duty in the midst of a PCS move.

Hecht noted in his email that the novel coronavirus “has required extraordinary effort from our Sailors to meet the essential tasks of sending new Sailors to the fleet.”

“We deeply appreciate the hard work of everyone at Fort McCoy who keep the recruit training process flowing,” he said. “We constantly work to provide them with rest and relaxation opportunities as manning levels and mission allow.”

Any McCoy sailor concerned about their physical or mental health “is encouraged to speak with their supervisor as soon as possible so that we can address their concerns,” Hecht said.

Geoff is the managing editor of Military Times, but he still loves writing stories. He covered Iraq and Afghanistan extensively and was a reporter at the Chicago Tribune. He welcomes any and all kinds of tips at geoffz@militarytimes.com.