Despite suffering from a skin condition as beyond his control as his skin color, the Black Navy chief placed grooming standards above the damage that shaving wrought on his face.

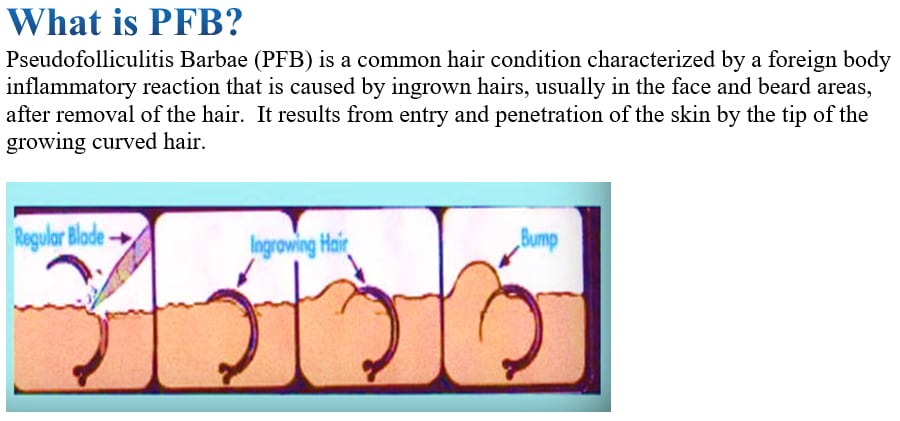

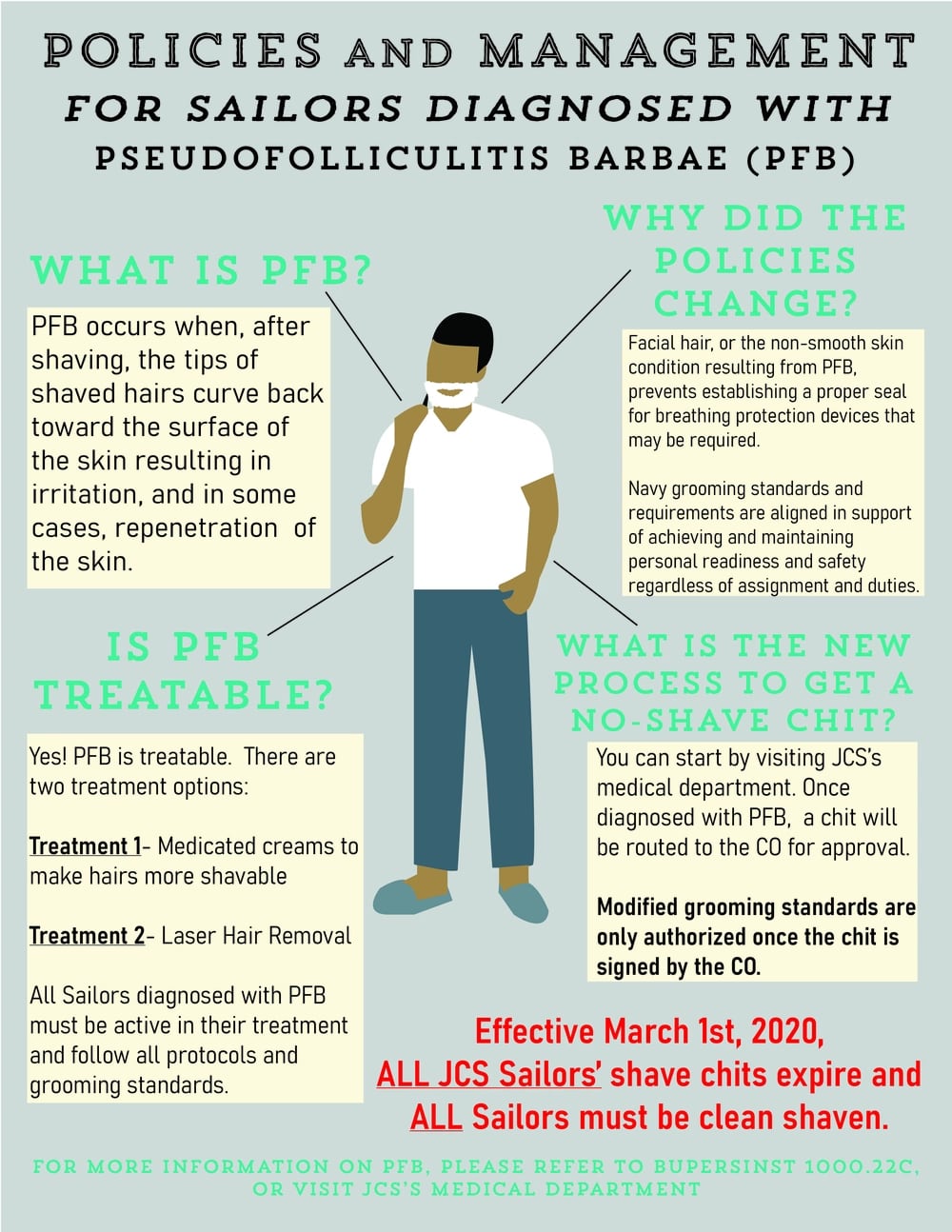

Roughly 45 percent of Black servicemembers grapple to varying levels with pseudofolliculitis barbae, known in the military as PFB and to the civilian world as razor bumps.

Like several Black Navy men who spoke with Navy Times for this report, the chief realized he had the condition years ago, when he started shaving daily in boot camp.

Each day, those cut hairs curled back and grew into his skin, producing a mass of angry, inflamed bumps on his neck.

“It became that you’re shaving over the bumps, that’s cutting the heads off them, you have bleeding and severe discomfort,” the chief said.

Those bumps had no time to heal before the razor came out again, he said, and medical did little more than recommend hot towels and tweezers.

He tried to shave the hairs in the recesses around the bumps. More pain, bleeding and scarring ensued.

But the chief gritted through it, because his superiors had told him to shave and the Navy was his future.

“I came from a super-small town,” he said. “Just me being in the Navy was a huge thing. I was willing to do just about anything to keep from going back.”

Like countless past and present PFB sufferers, most of them Black men, the chief eventually obtained relief via a shaving waiver, or “no-shave chit.”

Men of any race can suffer from PFB, but the curly nature of a Black man’s facial hair means it hits them particularly hard, afflicting up to three out of five African American men.

And according to several Black sailors who spoke with Navy Times, growing a beard brought them pain relief but ushered in a raft of professional obstacles, petty indignities and institutional side-eye from a Navy that has carried both a formal and informal aversion to facial hair for decades.

“You never see a sailor on a poster with a beard,” another chief told Navy Times.

‘The service isn’t meant for you’

Several Black enlisted and commissioned sailors suffering from PFB shared the same sentiment: that the Navy’s formal policies toward their condition — and the sea service’s informal attitude toward beards — renders them as less-than among their shipmates, even as the Navy has joined other American institutions in much-publicized efforts to better consider diversity following the police murder of George Floyd in 2020.

Because PFB mainly afflicts Black men, they say, Navy PFB rules and the norms surrounding shaving and beards end up discriminating against Black sailors in ways big and small, all because of a skin condition they were born with.

“The razor bump issue is actually as much of a rock in my shoe as Confederate flags on base,” one Black officer said. “The current climate sends a bad message to Black males that the service isn’t meant for ‘you.’”

The Navy is the only service that doesn’t allow permanent or years-long medical shaving waivers, a policy couched around safety.

But a new study launched last month at the direction of Navy Secretary Carlos Del Toro suggests such policies could change yet again.

Under the auspices of the department’s ongoing diversity, equity and inclusion efforts, the new study will offer a fresh assessment of whether a beard prevents a proper facemask seal during shipboard firefighting, while examining other literature on the topic and potential alternatives for bearded sailors and Marines.

The study could potentially lead to changes in PFB and beard policies that some Black sailors feel have unfairly singled them out for decades.

Black sailors told Navy Times they already have to work twice as hard to prove themselves as minorities in a largely white organization.

“You’re just adding to it with the beard,” a chief warrant officer said.

Dozens of Black sailors suffering from PFB contacted Navy Times to share their thoughts, and those interviewed for this report all requested anonymity for fear of being punished for speaking out.

Several said they almost understand where the punitive policies come from, given that the sea service’s largely white leadership has never had to live with or shave through such a skin condition.

They echoed a shared dilemma: Keep shaving over their razor bumps to fit in with the rest of the clean-shaven fleet and appease some bosses who don’t understand — enduring pain, scarring and skin made darker from ritualized razor abuse — or get a no-shave chit, grow a beard and look different in an organization whose ethos rests on everyone following the same standards.

Under policies the Navy changed only last month, PFB sailors faced severe repercussions for their condition.

They could be kicked out if they refused to undergo laser hair removal therapy, a painful regimen with mixed results that can impact a man’s ability to grow a beard for the rest of their life.

“I have seen the laser treatment scarring and blotches,” one officer said. “No thank you.”

While officials told Navy Times they have no record of a commander using laser therapy refusal to kick someone out, sailors said that fear has hung over many PFB sufferers throughout the years.

They also faced relatively minor indignities, such as carrying around their no-shave chit to produce for every nosy senior who wanted to know why their face was out of regs.

“A DDG is 505 feet,” one chief said. “You can’t walk five to 10 feet without someone saying, ‘let me see your no-shave chit.’”

Often, a sailor’s ability to even get a chit depends on whether they have a sympathetic commanding officer.

“Sometimes throughout my career, I had a very understanding chain of command, and sometimes I didn’t,” one chief said. “I was at my fourth command before I got my first no-shave chit. That lets you know about the process.”

RELATED

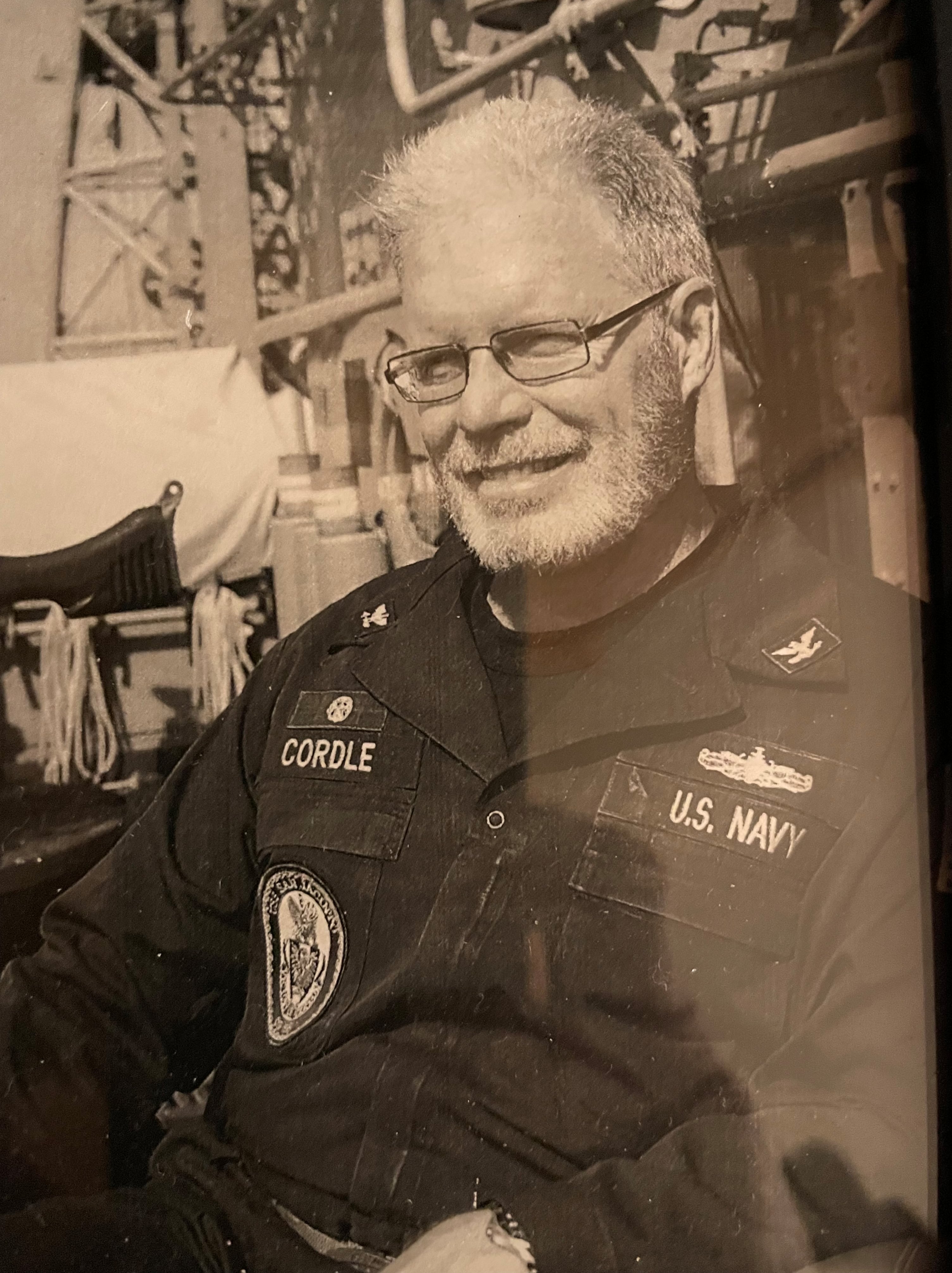

“On a personal level, is it discriminatory?” said John Cordle, a white retired officer who researched and wrote about how PFB policy affected Black sailors following Floyd’s killing. “I’m not picking on you because you’re Black, but you have a condition that only affects Black men and I’m picking on you because of that condition.”

“It certainly felt discriminatory to the folks I talked to,” added Cordle, who said he was “woefully misinformed” on the issue and its effect on his Black sailors while in command.

Although they spanned rates and ranks, the sailors interviewed for this report spoke of the same physical pain from shaving.

“The bumps start out small and they get bigger,” one Black chief said. “Sometimes it’s a little bit of pus that comes out. It feels like your skin is constantly on fire. You try to scratch it, that makes it worse.”

The Black chief warrant officer said his face looked “like the back of a Nestle Crunch” after shaving.

RELATED

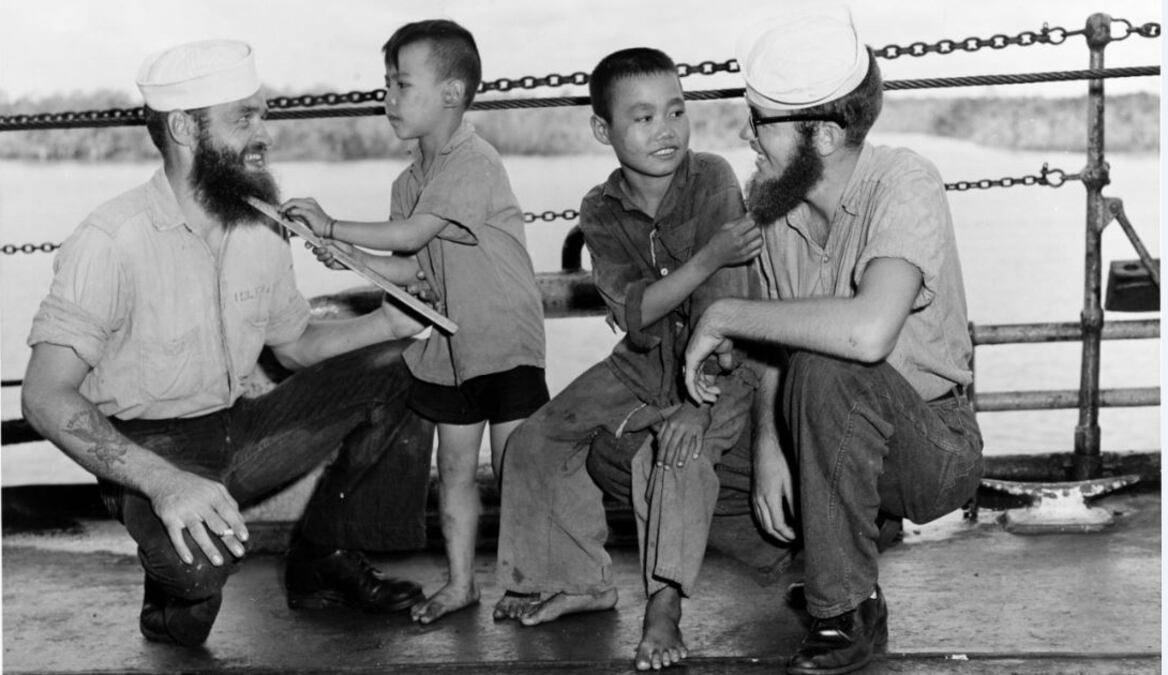

Such travails are not new.

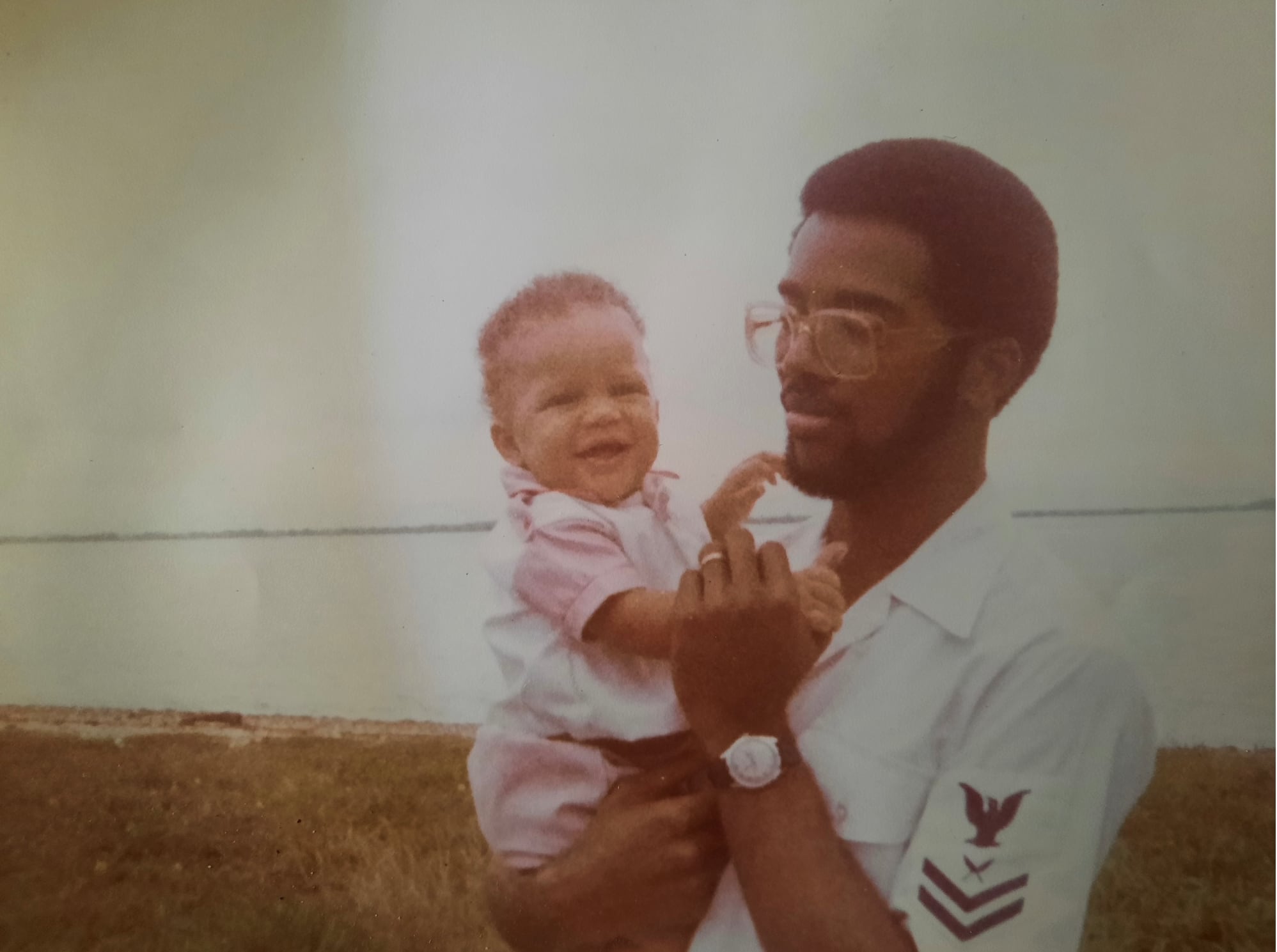

Decades ago while on active duty, Reuben Keith Green, a retired officer, and Raymond Kemp, the former fleet master chief for U.S. Naval Forces Europe-Africa, also suffered from PFB.

The Black old salts shaved and then sterilized a needle with a lighter before digging in and extracting the ingrown hairs at the heart of those bumps.

“I have pulled hairs more than an inch long out of my face that were burrowed into my skin,” recalled Green, a surface warfare officer who served from 1975 to 1997 and later authored the book “Black Officer, White Navy.”

“It’s like pulling a worm out,” he said. “I dreaded it.”

Once, Green didn’t wait for his skin to heal from the chemical burn caused by Magic Shave depilatory powder--a noxious hair removal option--and attempted to shave for a looming inspection.

“I wound up with these patches of skin coming off my chin and both cheeks,” he said.

To this day, Kemp said he can still smell the Magic Shave on his face, a burnt smell, “like a woman getting a perm.”

“It’s a very time-consuming and painful thing,” said Kemp, who retired in 2019. “It’s also very embarrassing.”

Several sailors said the fleet breeds animosity toward those who look different, and some end up viewing bearded shipmates as “shitbag sailors,” as one petty officer put it.

“We’re sailors just like you,” he said. “Let’s scab your knee up and we’ll shave it every morning and see how you like it.”

Not every Black sailor who contacted Navy Times reported feeling adversely affected by the Navy’s PFB and beard policies.

One Black chief said he was clean-shaven throughout his career and that more Black men need to learn how to use a safety razor, which can mitigate razor bumps.

Not every PFB-afflicted sailor who spoke with Navy Times was Black. White and mixed-race bearded sailors reported similar stigma.

One chief decried the notion that sailors pursue no-shave chits simply so they can sport a beard.

“There are a lot of people who wish they didn’t suffer from PFB so they wouldn’t go through this,” he said.

‘It’s like we have no voice’

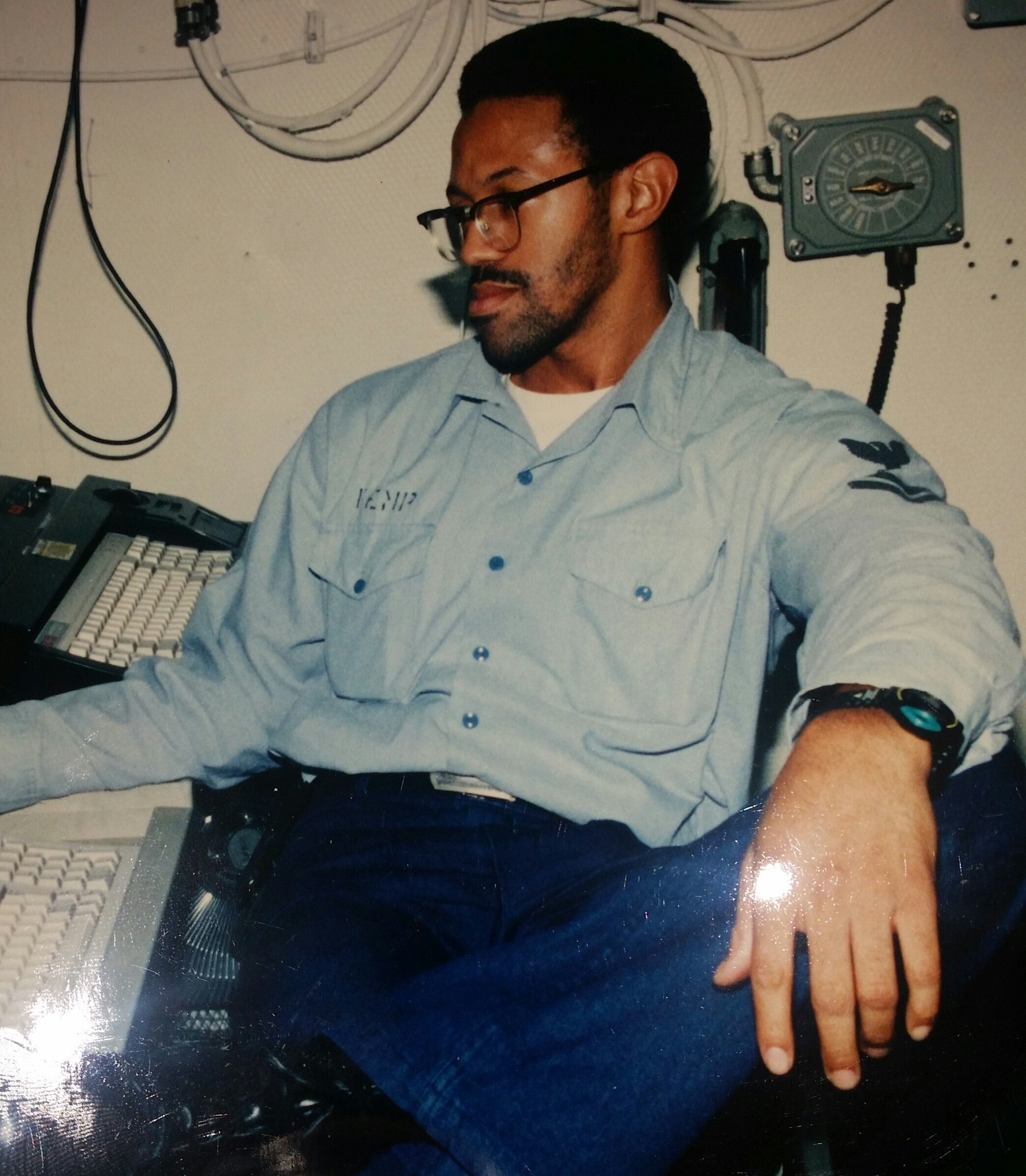

The majority of sailors who spoke with Navy Times for this report are Black senior-enlisted sailors and officers who have grappled with PFB for years.

Most spoke of their love for the Navy, but wondered why a skin condition for which they have no control makes it harder for them to wear the cloth of their nation.

Despite his PFB, one officer said he stays clean-shaven because he worries that a beard would affect his chance at promoting and make him stand out in the wardroom for all the wrong reasons.

“My face, despite careful shaving hygiene with a safety razor, is discolored and scarred,” he said. “It’s not natural, and frankly demeaning, that we are told to ‘get over it.’”

“It’s like we have no voice.”

Another Black officer said they have to choose between not shaving or “ruining their face, ignoring their pain, to fit in with their often-white counterparts or supervisors.”

The chief warrant officer still remembers the darkened skin on his grandfather’s neck, collateral damage from decades spent shaving through PFB as a soldier and police officer.

Earlier in his career, the warrant wondered if he would suffer the same fate.

“I’m risking my life being in the military,” he said. “Should I have to have scarring on my face even when I leave?”

The Navy has changed its beard policies several times over the years, arguably the most of any service, according to a 2021 Military Medicine journal report.

Beards were allowed for roughly 15 years spanning the 1970s and 1980s.

Earlier this month, the Navy updated its guidance again.

“Our shipmates diagnosed with PFB are dealing with a medical condition,” Chief of Naval Personnel Vice Adm. John Nowell said in a statement. “Our personnel should be treated with respect and understanding while going through any medical treatment process, such as for PFB.”

In one of the biggest changes, last month’s policy update for the first time allows sailors to sculpt and shape their beards so they can look like a squared-away military man.

“I can finally edge this up and not look like a hobo,” one petty officer noted.

Safety concerns

While the Army, Air Force and Marine Corps all offer PFB sufferers either permanent or multi-year shaving waivers, Navy policy has grown arguably more draconian in recent years.

In one of his most controversial personnel decisions — enacted before Floyd’s murder and America’s latest racial reckoning — Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Mike Gilday banned permanent no-shave chits in 2019.

When enacting the ban, Gilday and other leaders cited concerns over whether a bearded sailor could get an effective facemask seal when firefighting.

Prior to 2019, sailors were able to get permanent shaving waivers, a tacit acknowledgement that PFB is not a temporary condition that can be cured.

But these days, sailors have to shave using tactics prescribed by medical, then go show off their bumps, get a shaving waiver and do it all again in 90 days.

Some studies and sailor observations question the safety rationale.

Navy officials have in the past cited two Naval Safety Center reviews that found even a few days’ stubble might impact a mask’s seal.

But safety center records show just one incident in roughly the past 30 years where a beard affected a mask seal, involving a civilian shipyard worker.

The Navy currently limits beards to a quarter-inch length, but a 2021 Military Medicine article referenced assessments showing that half-face respirators were 98 percent effective with an 1/8-inch beard, and 100 percent effective with a 1/16-inch beard.

Several sailors who spoke with Navy Times said their masks sealed up just fine over their beards.

“I’ve worn gas masks in the field, I’ve worn gas masks for fit tests,” the chief warrant officer said, adding that Navy SEALs sport beards and manage to wear masks. “How are they swimming out of submarines with (full beards)?”

“I have also gone through the confidence chamber containing tear gas just fine without breaking a seal,” one petty officer said.

One chief wonders why he is expected to fight fires if he has a beard that Big Navy claims won’t allow him to get a proper mask seal.

“Why am I still on my ship’s in-port emergency team, and whenever we have to go to general quarters, I’m still on a damage control station that requires me to wear a (self-contained breathing apparatus)?” he said. “Sending me into a situation where you’re worried if I can or cannot have a seal and still having me go, that’s putting my life in danger.”

‘A company man’

On the deckplates, far from where Navy PFB policies are made, sailors have utilized different tactics to rein in their condition.

One chief had orders for a recruiting assignment and underwent laser hair removal therapy because his time in service taught him that recruiters are the face of the Navy, and sailors don’t have beards.

“Recruiters have to be this poster boy sailor,” he recalled. “This is the way I’m supposed to look.”

But every laser therapy session “was like sunburn,” the chief said, and the process permanently darkened his skin.

“My hair never did take to it,” he said. “At one point it just made my beard patchy, so I still had to shave it.”

As he climbed the ranks, retired Fleet Master Chief Kemp also realized he would need to abandon his beard.

“There was a senior chief who told me, ‘Kemp, you got to figure this out because you can’t go any further without shaving,’” he said. “If I was a company man, I need to look like one.”

He shelled out a couple hundred dollars for professional-grade edger, which he used to cut his facial hair so low that he appeared clean-shaven.

“The closest I could come to mitigating it was fooling people into thinking I shaved,” Kemp said.

As retired Lt. Cmdr. Green prepared to promote to the O-4 rank, a detailer called Green and asked if he wanted to become an admiral’s aide.

Green told the detailer about his PFB and his beard.

“I didn’t want to go to work for the wrong guy who doesn’t understand that and derail my career,” he said. “They took that under consideration and didn’t call me anymore.”

A chief recalled winning a prestigious military award a few years ago, only to see that the command article about his distinction didn’t feature any of the “setup pictures” of him on the job.

The chief was disappointed but not surprised when the admiral’s staff contacted his boss, asking about his beard.

“My CO stated, ‘well, yes, he has a no-shave chit, and his beard is in regulations,’” he recalled.

“We’re not going to run those pictures,” the admiral’s staff replied, according to the chief.

Another chief said nearly every man in his division has a no-shave chit, and that “we’re not looked at in a good light.”

“I don’t know if that’s part of the problem,” the chief said. “Whenever I ask if there’s something we’re doing wrong, everything is always perfect.”

RELATED

While PFB predominantly affects Black men, white and mixed-race sailors suffering from the condition recalled their own stigma.

A white petty officer said he once went to medical and was told he couldn’t get a no-shave chit.

“They could see it, but they still didn’t want to do it,” he said. “It quote-unquote only affected Black guys.”

‘A compassionate ear from the unimpacted’

Making the Navy a more inclusive place for PFB sufferers would involve formal and informal changes, active-duty and retired sailors say.

One chief warrant officer noted a conversation with a senior chief who was pushing for every bearded sailor in the command to either shave or get laser treatment.

“He was like, ‘I don’t understand all of these cultures,’” the warrant recalled the senior saying. “I was like, ‘hold up.’”

“When you say the statement, ‘I don’t understand these cultures,’ and you’re supposed to be the senior enlisted advisor to the captain, that’s saying something. Keep yourself out of it.”

On the policy side, Kemp thinks universal clean-shaven should remain the goal, and the Navy should pioneer medical research to make this possible.

As a former CO, Cordle thinks future leaders in pipeline training should watch a video on the condition so that they’ll understand their PFB-afflicted sailors better.

He also thinks the Navy should consider a pilot program where shore-duty sailors are allowed to grow beards.

Times change, Green noted, and so has the Navy’s institutional attitudes toward women’s hair, tattoos and other onetime cultural flashpoints.

“Is the objective to have a fully functional, qualified fighting force, taking into account the diversity of skin types, or is it to have the superficial … everyone has the same appearance?” Green said.

One chief said he thinks every man in the Navy should be able to grow a beard.

“If you have a lot of PFB sailors with beards and no one else can get one, it’s always going to be looked at in a bad light,” he said. “It’s something one sailor can get but another sailor can’t.”

At the very least, by speaking out about his experience, Kemp said he hopes that shipmates who don’t have PFB can better understand those who do.

“There must be a compassionate ear from the unimpacted for there to be a real change,” Kemp said.

Geoff is the managing editor of Military Times, but he still loves writing stories. He covered Iraq and Afghanistan extensively and was a reporter at the Chicago Tribune. He welcomes any and all kinds of tips at geoffz@militarytimes.com.