Five years ago, any sailor, veteran or Navy watcher would have been understandably skeptical of the guided-missile destroyer Fitzgerald ever returning to operations.

A collision with the cargo ship ACX Crystal off Japan on June 17, 2017, killed seven crewmembers in their berthing quarters.

It left the warship with a 13-by-17-foot hole in its starboard side, spanning several decks, and the commanding officer’s quarters had been obliterated as well.

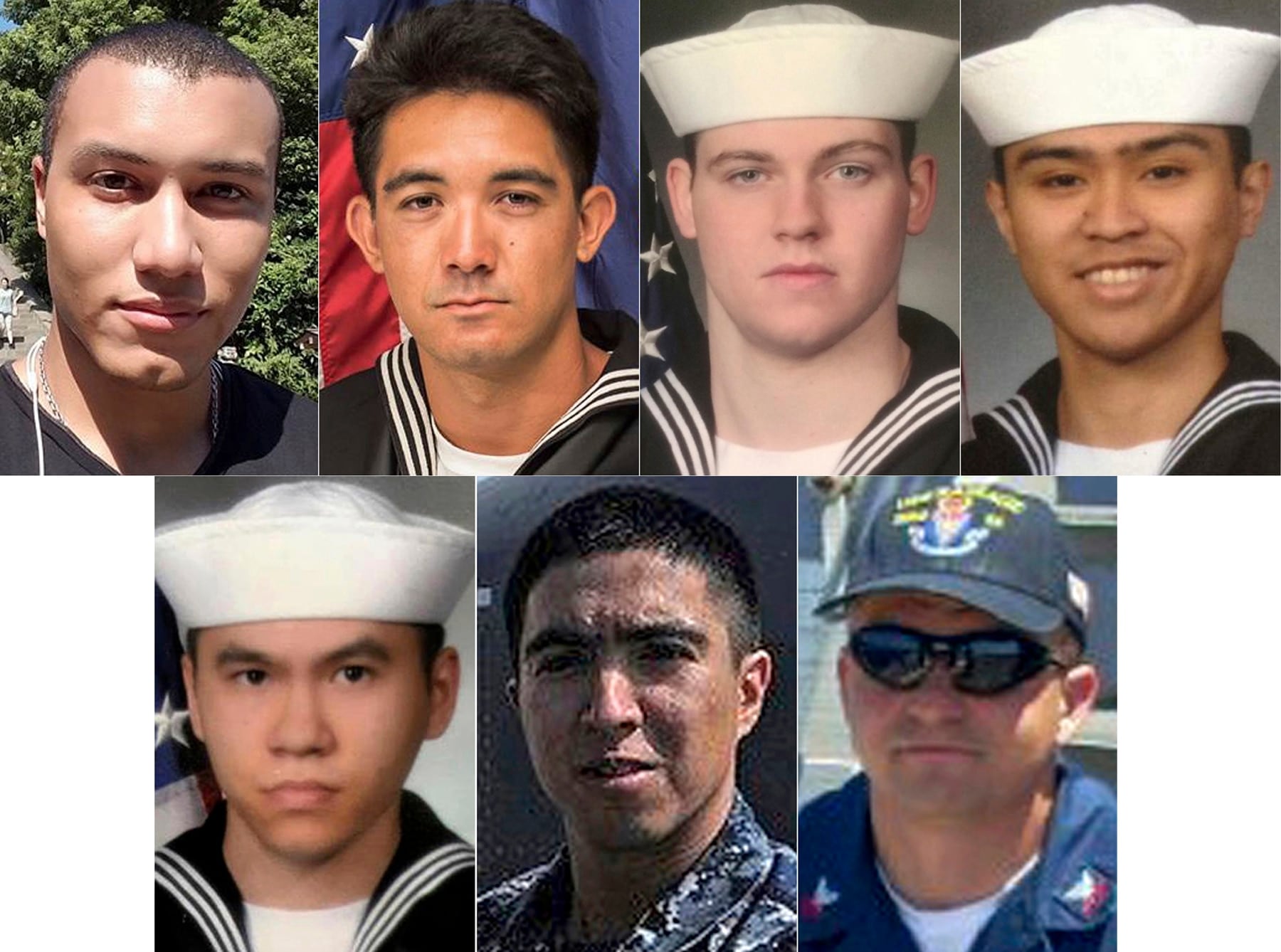

But five years later — even as the loss of crewmembers Shingo Douglass, Noe Hernandez, Tan Huynh, Xavier Martin, Gary Rehm, Dakota Rigsby and Carlos Sibayan continues to reverberate through the lives of those who loved them — the Fighting Fitz has returned to the fray and recently wrapped up its first post-collision deployment.

After the Navy spent years and hundreds of millions of dollars getting Fitzgerald back into fighting shape, the momentousness of the ship’s January-to-August deployment this year with the Abraham Lincoln Carrier Strike Group wasn’t lost on the destroyer’s leadership or its sailors.

Every step working up to and during the deployment carried added weight and meaning, the Fitz’s commanding officer, Cmdr. Dave Catterall, told Navy Times this week.

Everything was a milestone, he said, the first time the ship had done a given task since the harrowing collision.

“There was already an understanding we’re bringing Fitz back,” Catterall said. “We wanted to show Fitz in a good light, because we knew that people were watching Fitz, whether those were families of the fallen sailors, or our namesake’s family, we knew that people cared a lot. … That was important.”

The gravity and sanctity of getting Fitz back out there hit early in the deployment, during a January port visit to Yokosuka, Japan, where the warship was based before the collision.

Former Fitz sailors and those who had helped the ship after the collision came to check out the revitalized vessel, Catterall said.

“We were proud that they left with a positive impression of how the ship looked and where we were,” he said.

On June 17, Fitz’s crew held a memorial for the seven lost, five years ago to the day.

It was a chance to remember their fallen comrades, but also a chance to remember the grim consequences when a ship isn’t operating correctly.

Investigations into the Fitz collision revealed a culture of dysfunction not only onboard the ship, but within the Japan-based U.S. 7th Fleet as well.

“In that remembrance ceremony, we tried to focus on those sailors who were lost and the families, and what it means to be out there, not just for those families, but families that send their sailors out to sea” in general, Catterall said. “The importance of professional competence, and thoughtful planning, and good debrief practices to apply lessons learned … that was wrapped into that, but the primary focus was on remembering the cost that is paid when things don’t go right.

“It was a pretty significant milestone and we honored that at sea, in the waters of the Pacific, the same waters the collision happened in,” he added.

There were other moments from this deployment that remain with the CO.

When the ship pulled into Diego Garcia, the harbor pilot that brought Fitz into port was the same one who brought Fitz back to the Yokosuka waterfront after the collision, he said.

“It was almost by chance we ended up going to Diego Garcia, the way our schedule played out,” Catterall said. “So many little things on deployment reinforced how special it was.”

The Fitz’s “memorial pway” is adorned with a plaque remembering the collision, as well as seven plaques for the lost sailors.

The crew remembers what’s at stake every time they pass, Catterall said, and he brings newly qualified officers of the deck there “to reinforce the price that comes with not doing things properly.”

Even as the crew works to move the ship beyond the collision, that day is ingrained in the ship’s bones.

Sailors come in and out of Berthing 2 hatches through which survivors clambered upward as seawater filled the Fitz five years ago.

“I can’t speak for every sailor, I’m sure there were some who were apprehensive … but it wasn’t something that was evident in my conversations with sailors,” Catterall said. “People were able to get past that.”

Lingering remnants of the ship’s trauma aren’t lost on Catterall.

He sleeps in the same CO’s cabin that was crushed in the collision.

“I’d be lying if I said there weren’t times when it crossed my mind,” he said. “If you look at the pictures of the CO’s cabin crushed, that’s where I sleep every night.”

But while the collision will forever be a part of the ship, class-wide berthing designs that impeded escape have since changed for the better.

Across the destroyer fleet, “kickout panels” are on racks, and berthing vestibule double doors have been replaced with curtains to eliminate egress choke points, according to Cmdr. Arlo Abrahamson, a Naval Surface Forces spokesman.

Some Fitz sailors who escaped the sea, which filled the berthing in less than a minute, later blamed lockers that weren’t bolted down strongly enough for impeding escapes.

Today, the “structural rigidity” of racks and lockers has been improved, Abrahamson said, and crews undergo mass egress training from their assigned racks.

In a long deployment that took the Fitz to Japan, India, Sri Lanka, Bahrain and back to its new homeport in San Diego, the crew kept the ship in the fight in ways that impressed the CO.

“I’ve never been on a deployment where we were just able to keep going, keep fixing things within days … diagnose and repair, stay in the fight,” he said. “Very impressive to me, based on my prior deployment experiences.”

The ship and crew also did well during their Board of Inspection or Survey, or INSURV, assessment last year, according to Catterall.

“The sailors understood their equipment and they took pride in ownership,” he said.

Fleet-wide, Catterall said he is proud of the rapid advances in ship driving training he is seeing among junior officers.

He came up during the bad old days of “SWOS in a box,” where surface warfare officer training was a shadow of what it is today.

“I was commissioned, went to the waterfront and was given a stack of CDs to learn this stuff,” he recalled.

But today, officers coming out of the basic and advanced division officer courses are much more prepared to get to it when they arrive, Catterall said. He also lauded advances in quartermaster and junior officer of the deck schools.

Several SWOs who spoke with Navy Times this summer echoed this sentiment, that the surface fleet’s fundamental training has changed quickly over the past five years — for the better.

RELATED

“I don’t know offhand how many OODs I qualified on deployment, but it was over 10, and I could definitely sleep soundly when they had the watch,” Catterall said. “When they get their qualification, they fully understand what they’re doing, and they’re supported by a team in (the Combat Information Center) and engineering that has worked together and communicated well.”

Sailors inevitably develop an affection for their ship, and ships take on the personality of their crews, Catterall said.

“That crew sets a culture,” he said. “That culture is difficult to change.”

That has become a main driver of Fitz’s crew these days, moving the warship beyond the collision and into a place where it is in the fight, and not just a casualty.

“This is an opportunity for us to set the right culture and create an environment we would be proud of for years to come,” Catterall said.

While never forgetting the fatal mistakes of the past, the Fitz is starting to write the next chapter of its service.

“I’m confident the Fitz is back,” Catterall said, “and we’re focused on continuing to get better.”

Geoff is the managing editor of Military Times, but he still loves writing stories. He covered Iraq and Afghanistan extensively and was a reporter at the Chicago Tribune. He welcomes any and all kinds of tips at geoffz@militarytimes.com.