The suicides of three junior sailors assigned to the aircraft carrier George Washington over six days in April were not connected, according to a Navy investigation into the deaths released this week.

But the probe nonetheless reveals systemic Navy shortcomings and raises more questions about the state of the Navy’s mental health services, a shortage of providers that is echoed across America.

It also shows the ignorance that higher-ranking sailors had of the plight of some of their junior brethren, and an institutional indifference to how bad life can be in the shipyards.

Retail Services Specialist 3rd Class Mika’il Sharp killed himself April 9, Interior Communications Electrician 3rd Class Natasha Huffman died by suicide the next day and Master at Arms Seaman Recruit Xavier Mitchell-Sandor ended his life April 15.

While their deaths are not directly attributed to conditions aboard the aircraft carrier George Washington, the probe shows that all three young adults were going through hard times in their own way.

RELATED

At the time of their deaths, conditions had become grim aboard George Washingon, which has been undergoing a lengthy refueling and maintenance period in a Virginia shipyard since 2017. It was supposed to be out by 2021 but is now expected to leave Newport News Shipbuilding next year.

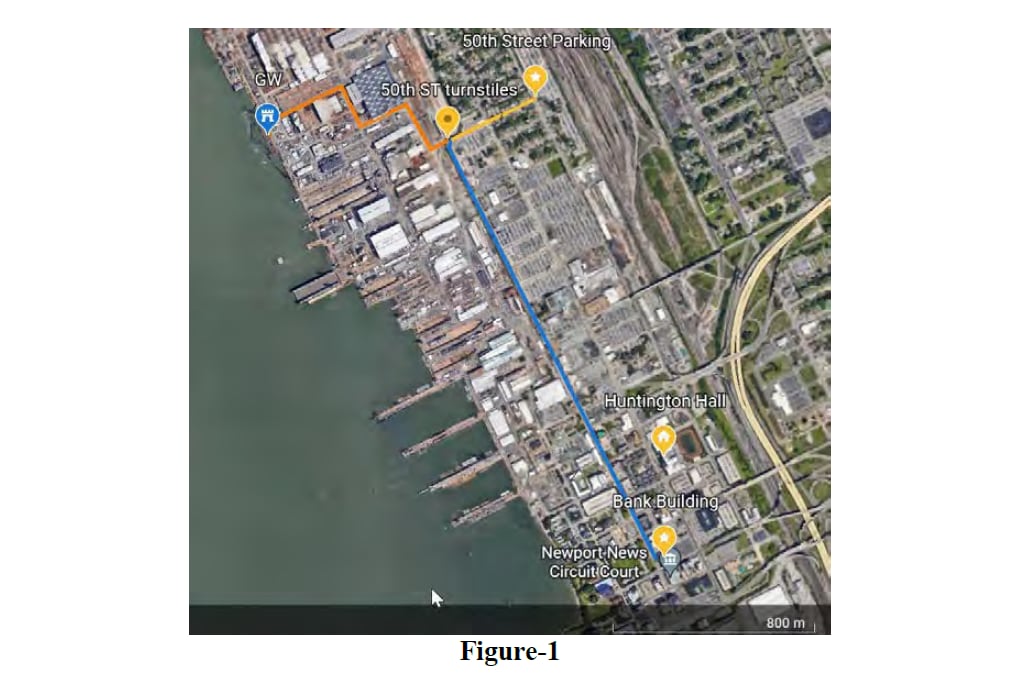

This overhaul turned the ship into a giant construction site in which some sailors like Mitchell-Sandor lived, where heat and hot water were intermittent, it was a mile-long walk to the parking lot and sailors onboard were left with little to do in their off hours.

While Sharp, Hoffman and Mitchell-Sandor were all assigned to GW, its conditions were only found to have played a role in the death of Mitchell-Sandor, according to the investigation.

Troops and veterans experiencing a mental health emergency can call 988 and select option 1 to speak with a VA staffer. Veterans, troops or their family members can also text 838255 or visit VeteransCrisisLine.net for assistance.

At least seven GW sailors died between April 2021 and April 2022, with at least four of those deaths ruled as suicides, officials said earlier this year.

The investigation released Monday focuses on the deaths of Sharp, Huffman and Mitchell-Sandor.

A fourth sailor, Machinist’s Mate Fireman Connor Owens, was found to have died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound in December 2021, according to Virginia officials.

RELATED

Further details on the other GW deaths have yet to be released.

“While there were common stressors amongst the three GW Sailors who died on or about April 2022, such as the general stress associated with conditions in the shipyard environment, it is the opinion of the investigation team that the deaths of RS3 Sharp, IC3 Huffman and MASR Mitchell-Sandor were not related or connected,” the investigation states. “Each Sailor was experiencing unique and individualized life stressors, which were contributing factors leading to their deaths.”

Accepting ‘the status quo’

The Naval Air Force Atlantic investigation notes that the 19-year-old Mitchell-Sandor had few elder sailors looking out for him or helping him adjust, and suggests that older sailors and officers have forgotten how jarring Navy life can be when a young adult first joins the fleet.

AIRLANT’s commanding officer, Rear Adm. John Meier, wrote in his investigation endorsement that a broader probe into quality of life issues for sailors in the shipyards will drill down on topics that the higher ranks may take for granted.

“It is safe to say that generations of Navy leaders had become accustomed to the reduced quality of life in the shipyard and accepted the status quo as par for the course for shipyard life,” he wrote.

The probe also raises troubling questions about how Huffman even got to the point where she was able to take her life in her off-base apartment, as she had had several reported mental health issues beforehand and a prior suicide attempt in 2020.

On the provider side, the investigation reveals how overworked the mental health cadre assigned to George Washington was at the time.

The ship’s psychologist, known as the “Psych Boss,” and the behavioral health technician, or “Psych Tech,” are described as “overwhelmed” in the report, and the investigator notes that they require extra resources to keep up with the demand.

Navy higher-ups sent additional resources to help GW after news of the suicide cluster broke earlier this year, and improvements to shipboard life while a carrier is in the yards are ongoing.

Former Master Chief Petty Officer of the Navy Russell Smith and other leaders have warned this year that the Navy is struggling to fill all its mental health jobs, a reflection of a nationwide shortage in such providers.

The now-retired Smith attracted scrutiny when he visited the GW crew right after the suicides. A video of the all-hands leaked in which he told the wary sailors that things could be worse, and they could be living in a foxhole.

GW reported at least 2,600 mental health encounters since January 2021, a patient load divvied up between two substance abuse counselors, the ship’s psychologist and the technician.

“Between Psych Boss and Psych Tech, they see between 5-20 patients each day and have a significant backlog for initial appointments, ranging from 4-6 weeks,” the investigation states.

RELATED

Even as GW’s mental health officials struggled under a relentless crush of patients in need, the Psych Tech told investigators that leadership and leading petty officers “‘don’t have time’” to deal with these issues and just refer them to the mental health office.

Big Navy has identified Deployed Resiliency Counselors, or DRCs — licensed civilian clinicians now assigned to all carriers and amphibious assault ships —as an extra tool to help sailors.

But the GW investigation found that the carrier’s DRC was three miles from the shipyard, and many sailors did not even know there was a DRC to whom they could turn.

“Multiple Sailors interviewed stated they had not seen, or had hardly seen, the DRC onboard the ship,” the investigation states. “Multiple Sailors interviewed did not know who the DRC was, what the DRC offered, or where the DRC was located.”

Some GW sailors told investigators they don’t seek help for fear it would impact their career.

Sailors in Mitchell-Sandor’s security department worried they would be “red tagged” and prohibited from carrying a firearm if they reached out for help.

The Navy continues to experience ship maintenance backlogs, and the investigation shows that the ship’s prior commanding officer, Capt. Kenneth Strong, was pressured to get his crew back aboard the ship in April 2021.

Strong told investigators “there was pressure to get ‘out of the way’” for fellow carrier John C. Stennis, which needed the berthing barge that was housing GW’s crew so that Stennis could begin its own overhaul in the Virginia shipyard.

Strong also said moving the crew back on the carrier even as work progressed would allow them to hit a milestone and “take back ownership of the GW.”

“He stated that the GW ‘needed a victory,’” the investigation states.

Capt. Brent Gaut took command in June 2021 and said that sailors were moved to berthing spaces that were not suffering power or water outages, but the investigation shows that life was loud and hard aboard the carrier around the time of the suicides.

“There is always a Head you can find with hot water, but you do have to go looking for it,” the ship’s command master chief told investigators.

The investigation also indicates that senior enlisted leaders were not tracking the grim living conditions of their junior sailors, who often did not have the money or know-how to make off-ship arrangements like their higher-ranking brethren.

“During the course of this investigation, multiple Sailors revealed their concerns with berthing spaces,” the investigation states. “When asked about these concerns, leadership at the E-9 level and above were unaware of some of the issues.”

The master chief for Mitchell-Sandor’s department reported that 25 of his 149 sailors were living “out in town on their own dime,” and that almost all were at the rank of E-3 and below. For those working on the ship, parking was a one-mile walk and some junior sailors opted to sleep in their cars.

Many crew members were working outside of their designated Navy job while GW was being overhauled.

Junior sailors told investigators they did not feel comfortable complaining to GW leadersihp about the living and working conditions onboard. Multiple sailors said they had no mentor, and others said they had “hardly heard” from their assigned sponsors after checking onboard.

“Multiple sailors interviewed felt it was depressing to work onboard the ship during (the overhaul),” the investigation states.

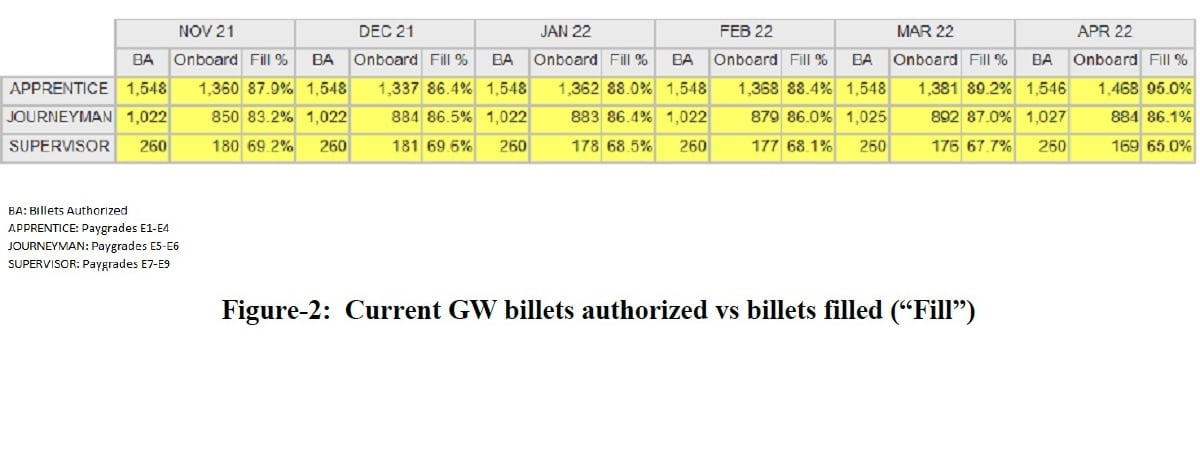

Chiefs were spread “really thin,” on the ship, and not all billets were filled, it states. Those staffing issues were mentioned by leadership this spring when news of the suicides first broke.

“Multiple Sailors reported leadership doesn’t want to talk about, or otherwise feels uncomfortable talking about, mental health issues with junior Sailors,” the investigation states.

Steps have been taken to make life more bearable for GW sailors still residing on the ship, including the installation of cell phone signal boosters inside the ship’s skin and wireless hotspots, along with more recreational services for off-duty sailors.

While Sharp, Huffman and Mitchell-Sandor were not in the same department, and life on the GW is not believed to have directly caused their suicides, the investigation did reveal tragic commonalities:

“Access to a readily available means to commit suicide, life stressors and a decision to follow through, coupled with an impaired mental state, led each of these Sailors to take their own lives.”

MASR Mitchell-Sandor

Of the three suicides, 19-year-old Mitchell-Sandor’s death was found to have been most closely tied to the conditions aboard GW.

He had been assigned to the carrier for just three months and had just turned 19 when he took his life in a GW bathroom April 15 while on guard duty, using his Navy-issued pistol.

The young man was dealing with several life stressors at the time and was suffering “significant sleep deprivation” due to his work schedule and the long trips he would take to see family in Connecticut and his girlfriend in South Carolina.

He did not like living in the the giant construction site that the carrier had become and would make those long drives out of state in part because of how bad it was aboard GW.

“These issues included cold temperatures, constant noise and periods without hot water or power,” the investigation states. On at least one occasion, on a 40-degree day, he had to use a bathroom that didn’t have any hot water.

Mitchell-Sandor worked nights and tried to sleep during the day as the ship — and therefore his berthing space — roared with construction noise. He kept a sleeping bag in his car and is believed to have been one of those sailors who slept in the parking lot.

The junior sailor “was offered an opportunity to move to a new berthing” when he raised concerns to leadership, but he declined, which the investigator wrote was understandable given his inexperience.

“Often Sailors will choose to avoid the hassle of moving their belongings around the ship,” the investigation states. “However, for a brand new 18-year-old Sailor, more senior Sailors, sponsors or mentors should have helped him to understand his options and encourage him to relocate.”

Mitchell-Sandor’s chain of command was aware that he took to sleeping in his car and counseled him.

“But there is no evidence of any follow through to understand the root cause of his decision making,” the investigation states. “More senior Sailors or an assigned mentor should have been there to support him and help him make decisions that were in his best interests.”

On the night of his death, a petty officer 2nd class offered to let him come stay at his off-base house.

“He communicated to his parents on multiple occasions that he believed his supervisors didn’t care about his concerns,” the investigation states. “His leadership at the E-9 level and above were largely unaware of his concerns with berthing.”

During his short time in the Navy, Mitchell-Sandor “committed multiple infractions,” including unauthorized absences and violations of COVID travel restrictions, as well as leave and liberty policies. But superiors didn’t document all these instances, and the investigator suggests it was to avoid negatively impacting the junior sailor’s career.

But if they had, “the red flags would have been more evident.”

“This may have provided the chain of command an opportunity to identify that MASR Mitchell-Sandor was struggling to adapt to military life,” the investigation states.

Two days before his death, after a 12-hour watch, he left the ship in the early morning of April 13 to drive the eight hours to his parents’ home.

The day of his death, April 15, he left Connecticut at 5 a.m. and drove more than eight hours to make it back in time for his next 12-hour watch, which began at 5 p.m.

Sleep deprivation may have increased his suicide risk, according to the investigation, which might have been avoided had the junior sailor been counseled about his absences and the unauthorized long trips.

“Off-ship housing would have enabled him to sleep without interruption and provide a needed physical separation from the ship and shipyard environment,” the investigation states.

His departmental leadership did not identify or adequately correct the issues around nightshift sailors having to sleep on the ship during the day while the loud overhaul work went on around them.

“Considerations should have been made to prevent Sailors that permanently reside on the ship from working on night shifts,” the investigation states.

On the night of his death, Mitchell-Sandor ducked into a bathroom for some privacy, where his female watch partner could not follow.

A petty officer found Mitchell-Sandor dying from a self-inflicted gunshot wound at about 9 p.m.

That petty officer “reported not having heard a gunshot, but may have heard a loud noise he attributed to (maintenance) work being conducted on the ship, as was a normal occurrence.”

IC3 HUFFMAN

Those who loved her described Huffman as having a lot of friends and being very funny.

She died by suicide at her off-base residence on April 10 and had not lived aboard GW since November 2021, according to the investigation.

Like the other two sailors that are the focus of the investigation, Huffman was “dealing with multiple life stressors which continued to build over time.”

The investigation notes that Huffman was and had been struggling with her mental health, and it raises questions about how she was allowed to remain in the Navy for several years.

Huffman had “34 confirmed prior mental health encounters” since joining .the Navy in 2018, including a previous suicide attempt in 2020. For reasons that remain unanswered in the investigation, her prior suicide attempt was not entered into the Defense Information Service System, as it should have been.

Nine of those 34 prior encounters happened when she was in her initial training at the Navy boot camp in Great Lakes, Illinois. There were no waivers in the sailor’s record, and Huffman’s pre-service mental health history should have disqualified her from Navy service, according to the investigation.

“The nine mental health encounters reported during her accession training pipeline should have indicated she was not qualified for Naval service and resulted in further review,” the investigation states.

RS3 SHARP

Sharp, 23, used a personal firearm to take his own life at a private residence on April 9.

He owned three guns and was not living aboard GW at the time, but was on temporary orders to attend barber school.

“RS3 Sharp was drinking heavily the night he died, which affected his decision-making ability,” the investigation states. “He was already dealing with multiple life stressors,” including within his marriage.

He reported feeling “stagnant” and not recognized for his work, even though he had been promoted days before his death via the meritorious advancement program.

While attending barber school, Sharp appeared to be happy, according to the investigation.

“RS3 Sharp’s decision to take his life was an impulsive decision influenced by multiple contributing factors, not directly related to the GW,” the investigation states. “RS3 Sharp’s work environment was not a contributing factor to his death.”

In his endorsement of the investigation, the head of Naval Air Forces, Vice Adm. Kenneth Whitesell, warned against treating the GW suicides as an aberration.

“We cannot assume these issues are isolated to a single ship, or to shipyards alone,” Whitesell wrote. “Rather, these three tragic losses brought to light the ultimate need to remain laser-focused on providing care and guidance to our Sailors.”

Geoff is the managing editor of Military Times, but he still loves writing stories. He covered Iraq and Afghanistan extensively and was a reporter at the Chicago Tribune. He welcomes any and all kinds of tips at geoffz@militarytimes.com.