Editor’s note: This book excerpt was first published in The War Horse, an award-winning nonprofit news organization educating the public on military service. It was republished with permission. Subscribe to their newsletter.

Author David Chrisinger spent the past four years walking in war journalist Ernie Pyle’s footsteps for his new book. This excerpt first appeared in “The Soldier’s Truth: Ernie Pyle and the Story of World War II,” from Penguin Publishing Group.

Yomna Mansouri cinched the belt on her coat as a rundown pickup loaded down with sheep blew past us. A blazing sun high in the clear December sky warmed my face and the top of my head. Once she was ready, we darted across the two-lane highway, hopped a concrete water pipe that ran the highway’s length, and landed in a ditch. The ground beneath our feet was spongy and uneven where the earth had healed over discarded plastic shopping bags, crinkled water bottles, and paper espresso cups. A stiff wind kicked up sand from the west, stirring the smells of modern life in rural Tunisia into an odd bouquet of damp earth, truck exhaust, and the sweet smell of barbequed camel.

“We will not be eating that,” Yomna told me when I asked about the food served up by the roadside eatery we passed a few hundred yards down the highway from where we parked.

On the other side of the ditch, a small field with neatly cultivated rows sprawled out before us. In the far corner of that field, two farmers Yomna had spotted, a man and a woman, picked onions with their two mangy dogs.

We were there to climb Djebel Hamra, the Red Mountain—a jagged, steep-sloped escarpment that juts out of the desert valley a short distance from the farmers’ field. On Feb. 15, 1942, Ernie Pyle scaled Djebel Hamra after he and several other correspondents were assured its summit would provide an unobstructed view of the Americans’ planned counterattack on the ancient camel-trading city of Sidi Bou Zid, which had fallen easily to the two German Panzer tank divisions the day before.

Despite the devastating losses sustained at Sidi Bou Zid, an impenetrable sense of denial blanketed the Allied high command over the border in Algeria. Rather than withdraw and regroup, they issued an order to counterattack more than 200 German tanks, half-tracks, and big guns with what little was left of the American force: a tank battalion, a tank destroyer company, an infantry battalion, and some artillery pieces.

“We are going to kick the hell out of them today,” an army officer told Ernie, “and we’ve got the stuff to do it with.”

“Unfortunately,” Ernie would report, “we didn’t kick hell out of them. In fact, the boot was on the other foot.”

When Yomna had picked me up from the hotel in Kasserine that morning, she told me that she wasn’t going to let me climb any mountain in Tunisia until she first talked with a local—a farmer—who knew the area well. Since the winter of 2012, Islamist terrorists had used the cave-rich mountains in central and western Tunisia to hide from the military and stage attacks.

“I don’t want you to end up on some ISIS propaganda video,” she told me from the back seat of our rental car as she queued up a playlist of her favorite Frank Sinatra tunes on her phone.

We met the farmer’s dogs first. Yomna stayed behind me, using me as a shield. The mixed breeds seemed friendly enough. They jumped up at me and nipped at the bottom of my jacket until the man whistled for them. We met and shook hands in the middle of the field, between rows of onions that looked ready to be picked. The man wore a dingy white scarf wrapped loosely around his head and a baggy black suit jacket and pants. Earth had worked into his pores and under his nails, and his hand felt cool and hard in mine. His wife stood behind him, squinting in the sun. Her colorful scarf looked handmade and much too nice to be worn while laboring in the dirt. Their faces were as wrinkled and weathered as their clothes, their eyes kind and watery from the wind.

Once I had exhausted my conversational French, which didn’t take long, Yomna spoke in the Tunisian dialect of Arabic—a mix of Berber, Arabic, and a little French—about my project, how I was there to write a book about a man who had watched a tank battle between the Americans and the Germans from the Red Mountain.

“You mean ‘Black Mountain’?” the woman said, pointing to it in the distance behind us.

I looked down at the map I had brought with me titled “Central Tunisia, 1943: Battle of Kasserine Pass.” Allied movements were marked in blue dotted lines. The Germans were red. With my finger I found Fäid Pass, where the Germans had launched their offensive. Halfway between Sidi Bou Zid and Sbeïtla, I looked for the mountain. It wasn’t there. I flipped to another map.

“Here,” I said looking to Yomna for confirmation. “This map calls it ‘Dj Hamra.’ Are we in the right place?”

“She says everyone always called it ‘Black Mountain,’” Yomna said with a shrug. “Maybe because it isn’t red?”

The man spoke to me in French. I nodded politely and waited for him to finish.

“He wants to know what Ernie looked like,” Yomna interjected.

He was a small man, I said, holding my hand flat against my sternum. About 110 pounds. When he was here, he was 42 years old, I continued. Thinning white hair on the top of his head. He had a big nose, too. People said he looked frail, like he was sick all the time.

Yomna translated. The man nodded. He looked down at the ground, then back up at me. His lips tightened. His brow furrowed. When he spoke, it seemed he was trying to comfort me, as if he were a doctor gently explaining the inoperable nature of a lump I had found.

I looked to Yomna as I folded my maps and slid them back into the inside pocket of my jacket. She took off her sunglasses and smiled.

“He says your friend is not there anymore.”

After thanking the couple for giving us the go-ahead to climb the mountain, Yomna and I hurried back to the car, where we found her cousin, Zakariya—our chauffeur for the week—leaned against the front fender, scrolling on his phone and finishing a cigarette. About a thousand yards up the highway we crossed a bridge and turned left down a dirt road that followed the edge of an olive grove. The road dissolved into more of a trail, with ruts so deep Zakariya had to stick his head out the window to navigate them. As we crawled along, Yomna cranked up the volume on Sinatra’s “You Make Me Feel So Young.” At the end of the trail stood a small stucco building, 10 feet by 10 feet and 15 feet tall. There was enough shade on the eastern side of the building for Zakariya to park and continue checking his text messages while Yomna and I hiked the rest of the way to the base of the 2,000-foot mountain.

‘But What if They Have a Gun?’

I scanned the ground, searching for any signs of the battle. Slit trenches or rusty C ration cans, maybe a rifle cartridge or shrapnel if I was lucky. Many American soldiers treated bits of shrapnel like good-luck amulets. In the half an hour it took Yomna and me to hike from the base of Djebel Hamra, there was nothing to be found but sand, shale, and flecks of mica that glittered in the sun.

The side of the mountain was steeper than it looked from a distance. With Yomna trailing behind me, I switchbacked across the south-facing slope. The sun baked the back of my neck. Dressed in tight black jeans and pearly white Adidas sneakers, Yomna kept pace with me until we hit a stretch made up of flat, loose stones. It was like trying to walk on dinner plates spilled all over the kitchen floor—Yomna slipped every few steps. She fell down hard on her side about three-quarters of the way to the top. I heard her break her fall with her elbow and hip. She winced in pain as I trotted back to where she had fallen and helped her regain her footing. Her right side was dusted with powdery soil, like flour.

“Is that a cave?” she asked as she dusted herself off.

“Where?”

“There!” she pointed up and to the left. “Right there! That’s a cave. That’s definitely a cave.”

A few hundred feet above us, a black hole big enough for a person to climb through stuck out among the light brown stones and green shrubbery.

“We need to turn back,” Yomna said. “We need to get off this mountain.”

For the first time in Tunisia, I occupied the exact ground Pyle had. We were so close, yet Pyle suddenly seemed to be drawing back, like a desert mirage. I took a deep breath. The cool breeze dried the sweat on the back of my neck.

“What if we hiked this way?” I said, pointing to the far side of the mountain, away from the cave opening. “Then if someone comes out of there, we’d have more time to go down.”

“But what if they have a gun?” Yomna asked. Her arms were crossed.

“We’ll be fine,” I tried to assure her.

‘I Felt Exhausted by Everything Left Unsaid’

After Yomna and I reached the summit of Djebel Hamra, I sat down on a flat rock next to a low shrub. When Ernie sat and took in the same sight back on Feb. 15, 1943, he was reminded of the high plains of the American Southwest.

“The whole vast scene was treeless,” with semi-irrigated vegetable fields broken up by patches of wild growth, he wrote. He saw “shoulder-high cactus of the prickly-pear variety” and the occasional stucco house, tiny and square. Through a pair of binoculars, Pyle viewed the smear of Sidi Bou Zid, 13 miles away, which Ernie described as “a great oasis whose green trees stood out against the bare brown of the desert.” Beyond Sidi Bou Zid loomed Djebel Lessouda and the infantrymen marooned there.

The vista Yomna and I spied from atop Djebel Hamra nearly eight decades later closely matched Ernie’s description. The dips and folds of the tan-brown plain below the mountain undulated like waves in the ocean. The sun sat high in the sky, shining brightly over a monotonous landscape of sand, gullies, and dry washes, broken up only occasionally by patches of dark prickly pears and the geometric patterns of olive orchards and irrigated farm fields planted by hand.

Sidi Bou Zid, 13 miles to the southeast, was a tiny spot of dark-hued greenery and cream-colored houses. Beyond the city, the purple ridges of Djebel Ksaira stood above an arid haze. To our left, rising majestically from inhospitable soil, we saw Djebel Lessouda. Other than the semitrucks barreling down the highway in the distance, the panorama seemed little changed since Ernie had been there to watch the Americans’ disastrous tank battle.

Looking out over the land, I tried to picture Ernie in his knit cap and brown army coveralls fading white from exposure and too many washings. I tried to picture his overshoes and the weariness of his features, his body bundled tightly in his double-breasted coat. I tried to picture him squinting into the sun, taking mental snapshots, waiting for the action to begin.

All I could envision was a young man, wavy-haired and silhouetted in a rising sun. It wasn’t Ernie; it was my grandpa, Hod. I’d read about what his tank company endured during the Battle of Okinawa, and I learned the details of the battle he had survived. It had been as devastating as the tank battle Ernie watched from atop Djebel Hamra. On April 19, 1945—the day after Ernie was killed—22 of 30 American tanks from my grandfather’s company were disabled or destroyed while attacking a village called Kakazu. It was, according to one historian of the battle, the greatest loss of American armor in a single engagement during the entire Pacific war.

I thought about the last time I spoke to my grandfather. It was in the summer, August, I think— the year before I started eighth grade. The battered shell of a rusted-out 1927 John Deere B tractor rotted in the front yard, overgrown with weeds. Crumbling concrete steps and a rusty pipe for a handrail led to the front door. My father went inside first, leaving me, my mother, and my younger brother in the yard. There was a hollowness in the air, a dark unspeakable silence as we waited for my father to return to the steps and give us the go-ahead to enter.

We filed into the tiny kitchen and lined up, tallest to shortest. With only a single kitchen chair to his name, no one except my grandfather could sit, not that I would have wanted to. The stained linoleum floor and the windowsill above the table were layered with dust and dead flies. The soles of my shoes stuck to the linoleum. His old stove and the week’s dishes piled up in the crusty kitchen sink mixed into a faint stench that seemed to hang in the air above our heads.

I remembered standing there before him, wondering to myself how long it had been since he’d handled the greasy wrenches piled up on the table where a guest might have joined him for coffee and a chat. It had been decades since he’d retired from the tractor repair shop he’d once owned with his father, and still, I remember the calluses and the fingernails lined with grease. I remember his eyes, a deep blue, like mine. I remember his face, rough and broken in a way that could have been handsome. I remember the sweet-and-sour smell of brandy on his breath and fixating on the way he dug the bloated knuckles of his left hand into the top of his thigh to keep himself propped up in his chair. He was almost like an exhibit in a museum. “The Lasting Effects of Unaddressed Combat Trauma,” his display placard would have read. Only no signage existed to explain what I saw and what it all meant.

My father did most of the talking. The weather was nice, he said. Nice for cutting hay.

He seemed so different while in his father’s presence. Diminished, somehow, hiding behind a carefree demeanor, as if what had become of his father was normal or acceptable. Then he talked about me and my brother, how we were playing football again that fall. Grandpa smiled with his toothless farmer’s grin. Were we practicing our war cries? he asked. My father laughed. I tried to follow his lead. Then my father patted me on the back. He smiled at me through clenched teeth. There was nothing left to talk about. We had been there only 15 minutes, and I felt exhausted by the tension, by everything left unsaid between my father and his.

‘I Can’t Help Feeling the Immensity of the Catastrophe’

Before sunrise Sunday morning, Feb. 14, 1943, Ernie slept inside an igloo tent at Gen. Lloyd Fredendall’s II Corps’ headquarters on the Algerian side of the border with Tunisia. For nearly a month, the frigid tent pitched at the bottom of a sunless valley had served as Ernie’s personal base camp. When he wasn’t poking at his typewriter perched atop a wooden crate he begged off a supply sergeant, he jetted up and over mountains and across barren stretches of frozen mud in an open-air jeep, the wind burning his face.

During most of January, the frontline units had been preparing for Operation Satin— designed to knock the Germans in North Africa out of the war by trapping them between a rock and a hard place. The rock was British Gen. Bernard Montgomery’s Eighth Army coming up on Erwin Rommel from the south; the hard place was Fredendall’s green-as-grass II Corps. Right before the operation was set to begin at the end of January, however, Gen. Dwight Eisenhower scuttled it because the Eighth Army had yet to arrive in Tunisia from Libya.

The rock in the equation was missing.

Rather than push east toward the Tunisian coast, Fredendall’s troops were split and scattered across hundreds of miles into a “bits and pieces war” aimed at keeping the Germans off balance until better weather afforded the Allies ideal conditions for a coordinated offensive.

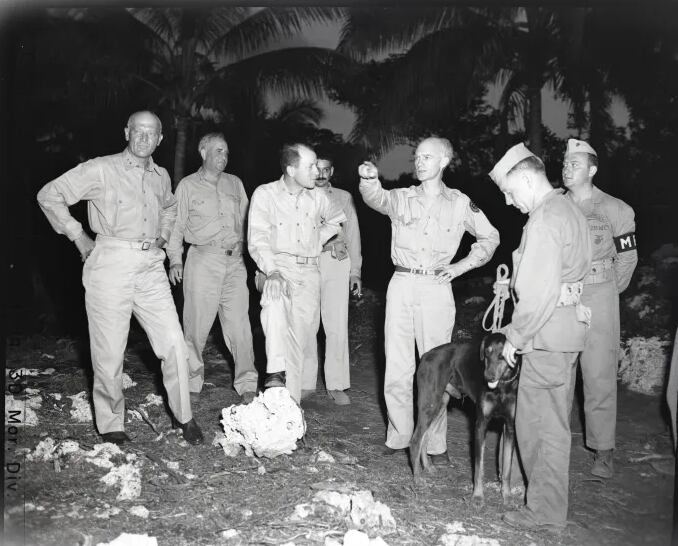

After Ernie reached the front dressed in his army coveralls, a private’s mackinaw, knit cap, and overshoes, he would catch up with a unit and do his best to blend in. After setting up his pup tent and laying out a heavy canvas bedroll stuffed with blankets, he visited foxholes and hung out by the mess tent, talking to soldiers and mentally recording the details of their everyday lives.

Most of his colleagues in North Africa weren’t doing that. They were mostly press association reporters tethered to Eisenhower’s headquarters staff back in Algiers. From the safe confines of seaside hotels, they attended press briefings, reviewed dry military communiqués, and churned out articles liberally sprinkled with vivid verbs like “smash” and “pound” that failed to impress on the folks at home any of the harsh realities of war.

Ernie, on the other hand, reveled in the “magnificent simplicity” and “perpetual discomfort” of life on the front lines, where he learned firsthand that the easy war Americans had come to expect—bolstered by articles that gave the impression that this place or that German division could simply be bombed out of the war—bore little resemblance to the terrifying reality on the ground.

After he’d gathered enough material, Ernie would strap on a pair of race-track goggles, bundle himself in a heavy army blanket, and travel back to his base camp in the valley with the windshield down so the glare wouldn’t attract the attention of a German dive bomber. But even with hot food in his belly, an endless supply of cigarettes, and a wonderfully warm combat suit Fredendall had gifted him, Ernie struggled to type with numb fingers in the bitter Algerian cold. With the icy wind drumming on his tent, snapping its flaps, Ernie’s head froze as cold as his fingers.

How could he possibly convey to the folks at home the disturbing duality of life at the front?

On the one hand, the front could be characterized by the loneliness, the danger, and the never-ending fear that combined to create an ugly imitation of life there.

“You just sort of exist, either standing up working or lying down asleep,” Ernie wrote after realizing the best path forward for him might be to simply describe what he had seen and felt, even if it didn’t necessarily speak to the bigger political questions about the war. “There is no pleasant in-between. The velvet is all gone from the living.”

On the other hand, there was also an electric excitement and an addictive sense of purpose and awe inherent in life at the front, something Ernie had never quite felt before.

“A big military convoy moving at night across the mountains and deserts of Tunisia is something that nobody who has been in one can ever forget,” he wrote.

With the sounds of tanks clanking and trucks groaning in low gear running through his mind on repeat, and the images of his friends’ faces painted white by the moonlight, Ernie continued: “I couldn’t help feeling the immensity of the catastrophe that has put men all over the world, millions of us, to moving in machinelike precision throughout long foreign nights—men who should be comfortably asleep in their own warm beds at home.”

‘We Wondered if the Officers Knew What They Were Doing’

“Word came to us about noon that the Germans were advancing upon Sbeïtla,” Pyle wrote of the remote, sun-parched city 85 miles east of Fredendall’s secluded headquarters. Feb. 14, 1943, was “a bright day and everything seemed peaceful,” Ernie noted as he raced toward the sounds of battle on that fateful Valentine’s Day. “The Germans just overran our troops that afternoon,” he continued, swarming out from behind the mountains around Faïd Pass on their way to the sleepy village of Sidi Bou Zid, about a dozen miles west. “They used tanks, artillery, infantry, and planes divebombing our troops continuously” in a blitzkrieg reminiscent of Germany’s armored offensives in the spring of 1940.

Characterizing the attack as a “German surprise” that swamped, scattered, and consumed the Americans, Ernie made it seem as if Fredendall and his commanders had simply been outfoxed by Rommel. The ugly truth was much more complicated than that.

Two weeks before the Germans began their five-day mauling—shortly after Eisenhower canceled Operation Satin—about 1,000 French troops defending Faïd Pass were killed or captured by a three-pronged attack spearheaded by 30 tanks from the 21st Panzer Division.

During the worst of the fighting, French officers begged Gen. Fredendall to rescue their two battalions. The general refused. Instead, because he was unwilling to weaken the defenses he established around Sbeïtla, Fredendall ordered only a dozen Sherman tanks and two battalions of infantrymen from the First Armored Division to counterattack the pass first thing the next morning.

Fredendall, it seemed, was far less concerned with the fate of the French than he was with the defenses being built at his command post in Algeria. For weeks before the Germans attacked Faïd Pass, Fredendall had a desperately needed regiment of engineers work around the clock to construct a pair of enormous underground shelters for him and his staff at the bottom of the valley.

With the French out of the way, and the Americans slow to react, the Germans had plenty of time during the night of Jan. 30 to fortify their defenses in and around the pass. The next morning, the American tank crews that had never been in combat before roared straight into the narrow pass, blinded by the rising sun. Interlocking fields of machine guns and mortars—along with a few 88 mm anti-aircraft guns—would be waiting for them.

From the razorback ridges on three sides, the Germans whipcracked round after round from their 88s straight down upon the vulnerable Shermans. Confusion and error, valor and misdeed—the tanks had stuck their necks straight into a German noose.

“The velocity of the enemy shells was so great that the suction created by the passing projectiles pulled the dirt, sand, and dust from the desert floor and formed a wall that traced the course of each shell,” an officer who was there later recalled. Within 10 minutes, half of the American tanks had been transformed into metal funeral pyres. The few that hadn’t yet been knocked out hauled out of the pass in reverse as quickly as they could, careful to keep their heavily armored fronts pointed toward the thundering German muzzle flashes.

Tankless survivors stumbled through the mud and over the corrugated vegetable fields west toward Sidi Bou Zid with the devilish hammering of the German’s new MG 42 machine gun all around them. My Great-Great-Uncle Robert was among the First Armored Division infantrymen who tried several times to stop the German advance. Each defensive position they tried to occupy, however, had already been overrun, and their attacks against the Germans resulted in nothing but heavy losses.

The next day, the Americans counterattacked one last time. Two infantry battalions hiked up the ridgeline three miles south of the pass in the hopes that they could outflank the German positions that had torn the Shermans apart the day before.

As one officer later wrote, the Germans “held their fire until we were practically at the foot of the objective. The men got a terrific raking over by the enemy as they fell back.” One commander signaled the general in charge of the attack, Raymond McQuillin, that there was “too much tank and gunfire. … Infantry cannot go on without great loss.”

Not long after, 15 panzers swung out from the pass and fired along the length of American infantrymen with their long-barreled 75 mm cannons from the left until they were checked by countercharging Shermans.

“They shook us like we had been dragged over a plowed field,” one sergeant later wrote.

The failed defense of Faïd Pass and the foolhardy American counterattack cost the French and the Americans dearly. More than 900 French soldiers were dead or missing. The American First Armored Division alone sustained 210 casualties. Faïd Pass was lost.

“We could not help wondering,” wrote an officer in his company’s war diary, “whether the officers directing the American effort knew what they were doing.”

‘You Are on Your Own’

Soon after he arrived in Sbeïtla, as the sun died down on Feb. 14, Ernie pitched his pup tent, ate supper, and went to bed. The next morning he caught a ride with two officers headed to a forward command post.

“Occasionally we stopped the jeep and got far off the road behind some cactus hedges,” Ernie wrote, “but the German dive bombers were interested only in our troop concentration ahead.”

When they finally reached the command post, Ernie found two acres of random vehicles and a few light tanks, along with only half of the troops who would normally staff a command post.

“Half their comrades were missing,” Pyle told his readers. “There was nothing left for them to work with, nothing to do.”

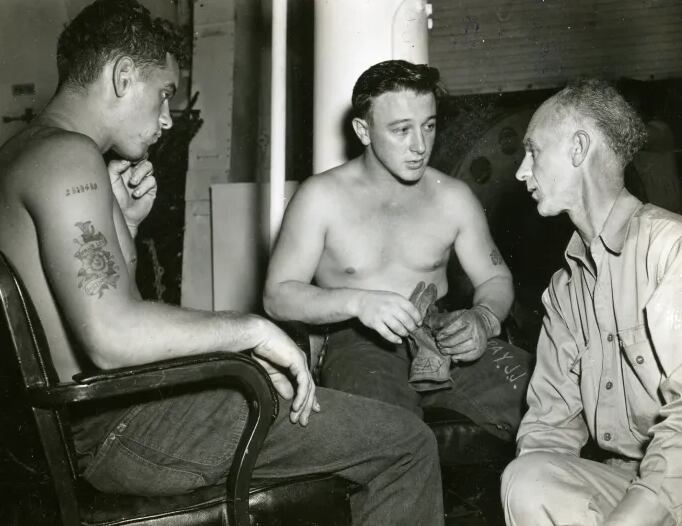

For the next few hours, Ernie sat with the men who “had been away—far along on the road that doesn’t come back,” and listened to their stories of near misses and miraculous survival.

“Not one of them had ever thought he’d see this dawn,” Pyle later wrote, “and now that he had seen it, his emotions had to pour out. And since I was the only newcomer to show up since their escape, I made a perfect sounding board.” Ernie listened without saying a word until the stories finally became merged into a generalized blur, “overlapping and paralleling and contradicting until the whole adventure became a composite.”

In the early hours of Feb. 14, two weeks after the first battle at Faïd Pass, more than 100 German tanks, including a dozen Tigers, had come across a small squad of American soldiers who were supposed to be on the lookout for a German attack through the pass, Ernie learned from the men. At the first sign, they were to fire rockets into the air, which would alert the artillerymen near Djebel Lessouda who had registered their guns on known features around Faïd. Fredendall believed that his men could use accurate artillery fire like a wall to keep the Germans from spilling out of the pass and into the desert below. By the time the artillerymen heard the rumbling of German armor and smelled the scent of diesel coughing from the back of at least 100 infantry lorries and half-tracks, every member of the squad was dead, their rockets still in the boxes.

From there, the Germans came across a company from the First Armored Division. Most of the crews, unaware an attack was headed their way, were outside their idle tanks cooking Valentine’s Day breakfast. In less than an hour, the Germans had reduced 16 of the company’s tanks to burning hulks of steel.

Emboldened by such quick and decisive victories, a group of about 80 German tanks and trucks then went north toward Djebel Lessouda while the rest headed south to envelop Sidi Bou Zid in a pincer movement, aiming to divide their forces and attack both flanks of the Allied defenses there.

In an order entitled “Defense of Faïd Position,” Fredandall explicitly dictated the positioning of units down to individual companies. Two prominent hills within sight of the pass were to be occupied, Fredendall wrote: “Djebel Ksaira on the south and Djebel Lessouda on the north are the key terrain features in the defense of Faïd. These two features must be strongly held, with a mobile reserve in the vicinity of Sid bou Zid.”

When Col. Peter C. Hains III of the First Armored Division saw Fredendall’s plan, he was disgusted.

“Good God,” he muttered.

He knew that any troops placed on the two hills would be marooned if a fast-moving attack swept around them. While the hills were mutually visible 10 miles across the desert, they were not close enough for defenders on one to help their comrades on the other. Fredendall’s orders resembled a defensive plan that might have worked during the first World War, without an appreciation for the speed and power of modern tank divisions.

American units fell like tenpins. East of Sidi Bou Zid, the Second Battalion of the Seventeenth Field Artillery—armed with a dozen and a half antique 155 mm howitzers—was erased. The Germans got “every gun and most of the men,” a staff officer later reported. Trying to avoid a similar fate after their forward observers were all killed or wounded, Battery A of the 91st Field Artillery dragged their dead to an empty trailer, tossed them in, and retreated to the west.

“We didn’t know exactly where to fire,” one platoon leader said. “There was artillery fire, machine-gun fire, armor-piercing tank shells whizzing through the town.” A captain in a jeep sped through the olive groves that sheltered the American supply trains. “Take off, men!” he roared over the noise of battle. “You are on your own.”

What happened next reminded an artillery lieutenant of the Oklahoma land rush, except that “the air was full of whistles” from enemy projectiles. Of the 52 American tanks that took on the Germans that day, only six survived past lunchtime. At 1:45 p.m., half a dozen German Tigers bulled through the rubble on the outskirts of Sidi Bou Zid. About three hours after that, tanks from the 21st Panzer Division in the south and those from the 10th in the north met two miles east of town.

The double envelopment had taken fewer than 12 hours to complete.

‘Then Came the Sound of Explosions’

At a quarter to three on Feb. 15, the battalion commander’s voice crackled to life over the radio, snapping Ernie to attention.

“We’re on the edge of Sidi Bou Zid and have struck no opposition yet,” the commander reported.

Across the parched plain before them, 40 American tanks and a dozen tank destroyers roared and poured blue smoke into the sand-dusted sky. Following in their dust plumes were trucks and half-tracks shepherding a battalion’s worth of infantrymen. Behind them came a dozen artillery pieces.

“The peaceful report from our tank charge brought no comment from anyone around the command truck,” Pyle wrote. “Faces were grave: It wasn’t right—this business of no opposition at all; there must be a trick in it somewhere.”

The Germans must either be much smaller than they thought—or they were biding their time, sucking the Americans into a trap.

As the outnumbered and outgunned American tanks reached the outskirts of the blown-apart village, a flare arced over Sidi Bou Zid, “like a diamond in the afternoon sun,” A.D. Divine reported from Djebel Hamra. Ernie and the other correspondents glued their eyes to their binoculars. Muzzle flashes blinked like Christmas lights near the town.

“Then, from far off, came the sound of explosions,” Ernie wrote.

German artillery airbursts ripped to shreds the artillerymen and their tubes pulling up the rear of the American attack. “Brown geysers of earth and smoke began to spout.”

Fredendall’s plan to counterattack two battle-hardened tank divisions with the reserve elements of a battalion that had never seen combat was doomed from the moment it was drawn out in grease pen on some map board back in Speedy Valley. The Germans held nothing back. Stukas dived and strafed. Panzers fired hundreds of armor-piercing rounds with a deafening report. Most of the dead had been killed in a small onion field two miles west of town. The bodies were twisted and bent into cruel angles. Maroon blood pooled atop the sand, and black smoke blotted out the sky. “One of our half-tracks, full of ammunition, was livid red, with flames leaping and swaying,” Pyle wrote of the peculiar sights and sounds of battle. “Every few seconds one of its shells would go off, and the projectile would tear into the sky with a weird whanging sort of noise.”

“As dusk began to settle, the sunset showed red on the dust of the Sidi Bou Zid area,” General McQuillin later reported. “There was no wind, and the frequent black smoke pillars scattered over the terrain marked locations of burning tanks.”

He counted 27 American tanks aflame, but “the heavier dust cloud near Sidi Bou Zid no doubt obscured more that were afire. It was easy to recognize a burning tank due to the vertical shaft of smoke.”

After the attack was aborted, four Sherman tanks rallied below Djebel Hamra. They were all that remained after the slaughter. All through the night, diesel-blackened tankers who had managed to escape their burning coffins stumbled back to the American lines in Sbeïtla exhausted and dazed.

“I found myself all alone wandering amongst the dead and wreckage,” said one. “The night had a dead silence except for a few howling dogs.”

By the next morning, it was estimated that the previous two days of fighting had cost the Americans at least 1,600 men, nearly 100 tanks, and plenty of half-tracks and artillery pieces.

Also lost that day, after so many had been led so ineptly, was confidence. Soldiers lost confidence in themselves and in their commanders; commanders in each other.

The “awful nights of fleeing, crawling, and hiding from death,” in Ernie’s words, had begun.

From The Soldier’s Truth by David Chrisinger, published on May 30, 2023 by Penguin Press, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2023 by David Chrisinger. This work was fact-checked by Penguin Press, and copy-edited by Mitchell Hansen-Dewar. Headlines are by Abbie Bennett.

David Chrisinger is the executive director of the Public Policy Writing Workshop at the University of Chicago’s Harris School of Public Policy and the director of writing seminars for The War Horse. He is the author of several books, including “The Soldier’s Truth: Ernie Pyle and the Story of World War II” and “Stories Are What Save Us: A Survivor’s Guide to Writing about Trauma.” In 2022, he was the recipient of the 2022 George Orwell Award.