Labor Day weekend was marked by the memorial services for Sen. John McCain of Arizona.

Eulogists described him as a patriot and a maverick, a generous man, and a hero.

Few challenged these salutes — although President Donald Trump famously suggested in 2015 that McCain was not a hero for being captured. While most disputed Trump’s remarks, candidate Dr. Ben Carson said, “It depends on your definition of a war hero.”

By any definition with which I am familiar, John McCain, a Vietnam War prisoner of war, was a hero. McCain deserves the honor not simply because he served. Not even just because he was captured — although he and the other Vietnam War POWs demonstrated remarkable courage and endurance and deserve the praise they have received.

But McCain was a hero because of his conduct as a pilot and as a captive. The descriptions of his captivity and the citation of his Silver Star award make this clear.

Today, approximately 1 percent of the U.S. population serves in the military. They are not from a demographic or geographic cross-section of the country. Most Americans do not know anyone who currently or recently served. No one under the age of 63 has ever faced being drafted.

One consequence of this distance from the military is less public understanding of what serving means. Perhaps, ironically, this has resulted in a greater public approval of those who do serve, describing all in uniform as “heroes.”

There is ample evidence that most troops are not comfortable with the general label of hero: if all are heroes, what remains to describe the truly heroic?

Achilles and Henry II may not have recognized 20th century weaponry or fortifications, but they would have understood and saluted Sgt. Alvin York in World War I and Audie Murphy in World War II — widely recognized heroes, Medal of Honor recipients who attacked, engaged and defeated the enemy.

In all of the American wars after World War II, political objectives shaped military strategy. Korea was marked by changing political goals, as was Vietnam.

Vietnam was a war of tactical maneuvers and small unit actions, with approximately 80 percent of ground combat engagements initiated by the enemy, a pattern accelerated in the post 9/11 wars.

In Vietnam, “winning” battles often became more a tactical goal of engaging the enemy and killing them, or at least deterring them — and then returning for another skirmish the next day or the next week. At or near the same ground. Winning was surviving.

The wars in Vietnam, Afghanistan and Iraq have been essentially wars of attrition, wars without crisp military objectives, and operations that, for the American forces, involved strict rules of engagement.

Assaulting enemy positions, streaming ashore in the face of hostile fire in places like Normandy or Iwo Jima, securing enemy defeat or surrender, raising a victory flag — these actions were far easier for non-combatants to understand and to celebrate. They fit comfortably into a public narrative in ways that the wars since then have not.

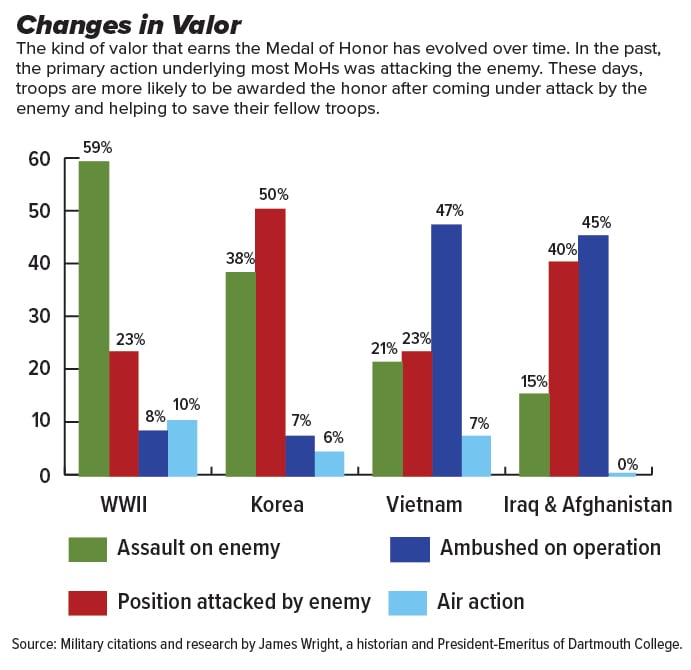

In World War II, more than 60 percent the 472 Medals of Honor went to those engaged in an assault on an enemy position. In Vietnam, a war of small unit actions, only 21 percent of the 260 men recognized with the nation’s highest medal were involved in offensive actions.

In World War II, 17 percent of the medals went to those who exposed themselves to enemy fire in order to protect or retrieve wounded comrades. In Vietnam, 44 percent of the awardees were cited for such heroic conduct. This trend has continued in our 21st century wars.

Just two days before Sen. McCain’s death, President Donald Trump awarded the Medal of Honor, posthumously, to the widow of John Chapman, an Air Force enlisted man who led a team into enemy fire on a snowy peak at Takur Ghar in Afghanistan and individually fought the enemy until his own death in March 2002. He went there in an effort to retrieve a wounded colleague.

President Trump said of him, “He gave his life for his fellow warriors.”

In Afghanistan, 50 percent of the Medal of Honor awardees, like Tech. Sgt. Chapman, were recognized for putting their lives at risk to save comrades.

For all of the combatants, these 21st century wars involve the daily courage of driving or marching off a base, or even existing on a base when presumed allies sometimes kill Americans, of patrols warily approaching a piece of trash or an animal carcass on the road, of encountering groups of civilians at a crossroads where fear, if not hostility, is present.

In these wars, firefights are with enemy combatants who are not wearing uniforms and can fade easily back into the civilian population.

There has been no ceremonial raising of victory flags in Afghanistan or Iraq — nor were there in Korea or Vietnam. Political protocol required that these not appear to be “American wars.”

But they were, and are, and yet because of their nature, they have been wars without traditional victory narratives.

The heroic victor, draped in laurel and hoisting a banner, enters folklore more readily than the young heroes who threw themselves on a grenade to protect others. And perhaps more readily than the young Navy prisoner of war who refused an opportunity to be released because others had been there longer than he had been.

Nonetheless, however heroism is defined, they are heroes all.

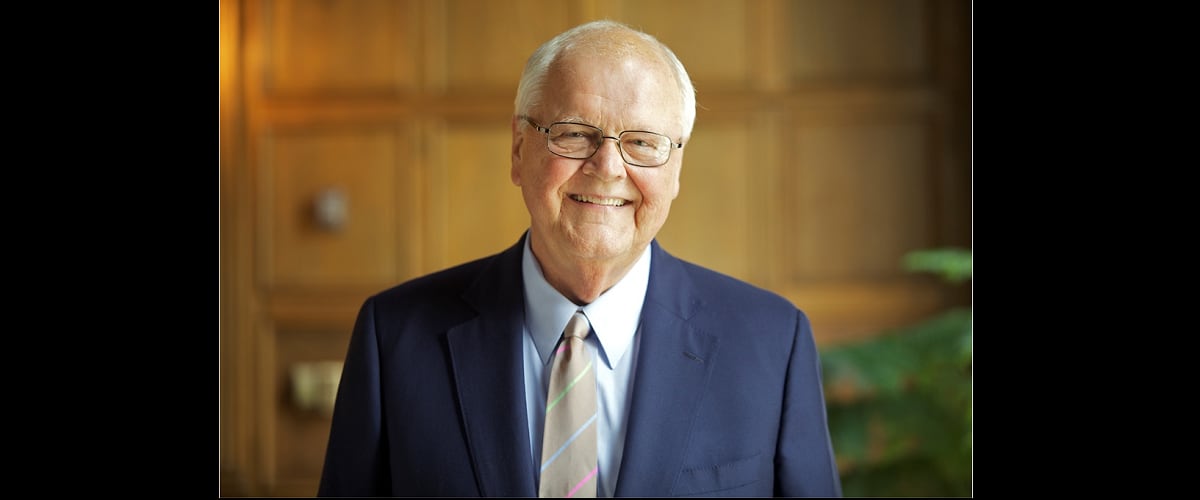

James Wright, a historian and President-Emeritus of Dartmouth College, served in the Marine Corps. His recent book, “Enduring Vietnam: an American Generation and Its War” was a finalist for the 2018 Dayton Literary Peace Prize.