On Dec. 8, 2020, Army Secretary Ryan McCarthy suspended or fired 14 military leaders for failing to adequately prevent, stop, or intervene in a culture of sexual assault and violence at Fort Hood Army base. This was necessary, but nowhere near sufficient.

The new secretary of defense in the Biden administration, Lloyd J. Austin III, has taken steps at the start of his service in this role to explore changes to the military’s handling of sexual and gender-based violence.

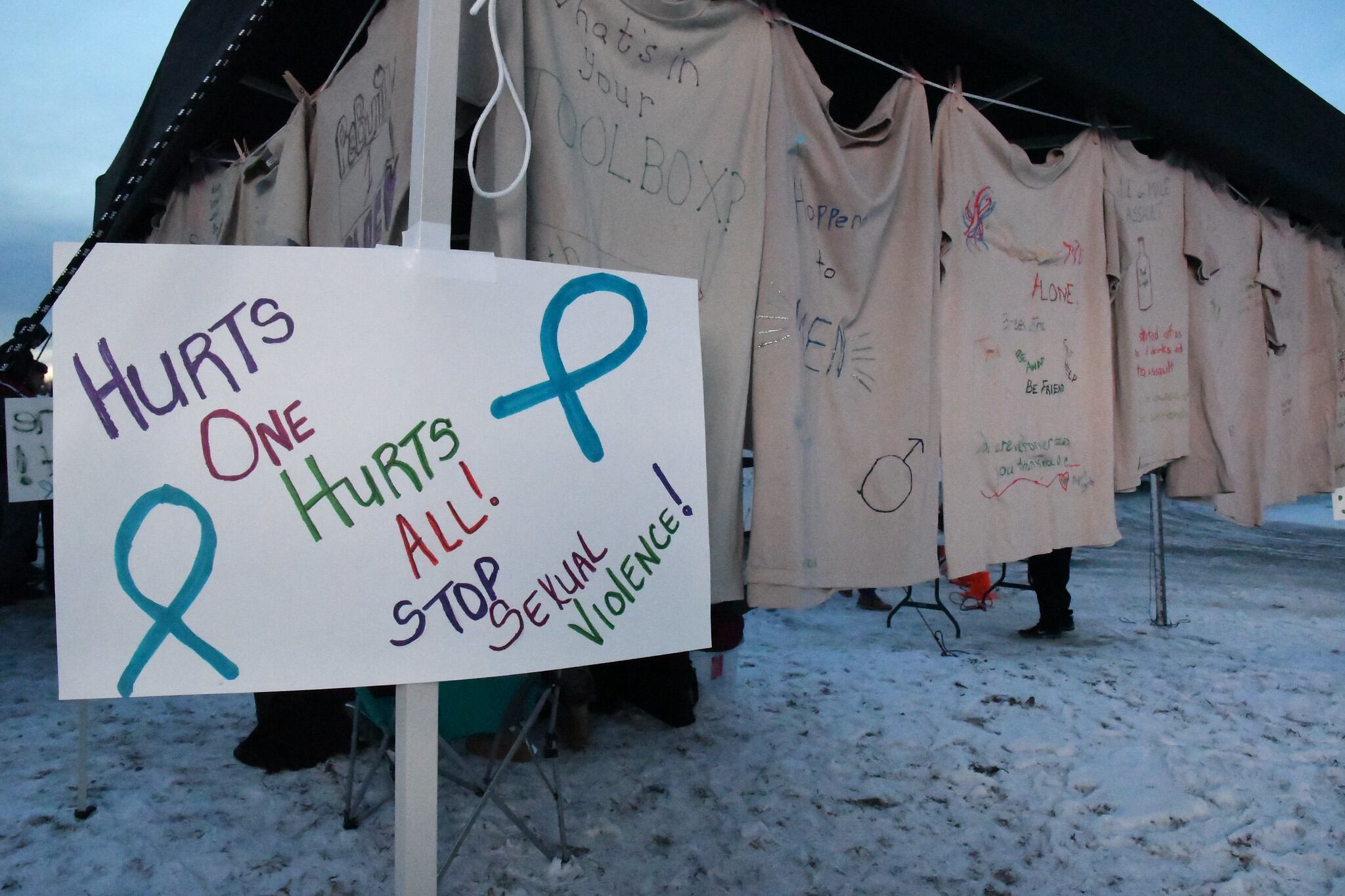

The investigation that led to these actions was prompted by a public outcry after the killing of Vanessa Guillén, a 20-year-old soldier at Fort Hood, by another soldier on the base. This brought to light preexisting concerns around the climate at the base, especially those related to gender-based violence. The independent council performing the investigation found a “permissive environment for sexual assault and sexual harassment,” and declared the system in place to receive and respond to reports “structurally flawed.”

Fort Hood is not alone in failing to protect military members from gender-based violence.

Such violence, which includes sexual assault and sexual harassment, is prevalent throughout society and prominent in military settings, which are by nature male-dominated and patriarchal. One in three women veterans receiving care from the Veterans Health Administration report having experienced sexual assault or harassment while serving in the military. The Fiscal Year 2019 Department of Defense Annual Report on Sexual Assault in the Military found a 3 percent increase in sexual assault reports by service members over the previous year, with the overwhelming majority of reports from women service members, and the highest rates among those serving in the Army. The true numbers, of course, are likely even worse than what we’re seeing, as underreporting of gender-based violence due to fear of retaliation, career impacts, and stigma is common.

Experiencing sexual violence during military service has particularly harmful health impacts. The lack of distinction between employment and personal life in the military context further complicates and exacerbates the impacts of gender-based violence and barriers to reporting and help-seeking. Military personnel are required to report experiences of interpersonal violence to their chain of command and to seek legal and medical remedies through that same system, rather than through civilian services. Service members experiencing violence may fear (and experience) retaliation from the perpetrator (who may also be a service member and even within the same unit or chain of command).

Gender-based violence is a major contributor to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), suicide, and other mental health and social issues among military service members and veterans.

It can also impact service members’ military employment and careers, resulting in a loss of benefits that come through military service and are unmatched in the civilian setting. Leaving military service can mean not only loss of income but loss of life-long financial, medical, and educational benefits that cannot be otherwise recovered.

A 2020 Government Accountability Office report found that women service members are 28 times more likely to separate from military service than their male peers, forfeiting career advancement, leadership opportunities and full retirement benefits, citing sexual assault as a key factor in the separation. Other research has also found premature separation from military service — with loss of benefits and achievement of goals — resulting from experience of gender-based violence during service.

The Fort Hood investigation report recommends policy and systems changes to reduce the tolerance and perpetuation of gender-based violence, including sexual harassment, and improve the response to those who experience violence. These changes are critical and long-overdue.

As chair of the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee, President Joe Biden spearheaded the passage of the 1994 Violence Against Women Act (VAWA), based on decades of anti-violence advocacy led by women’s movements. The new presidential administration needs to take action now and demand changes to culture, policy, and practice around sexual harassment, assault, and other violence within military settings.

Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand introduced the Military Justice Improvement Act (MJIA) in 2013 to reform reporting policies for sexual violence in military settings. This bill, or adoption of similar reforms, has yet to be passed. The new administration and DoD leadership should elevate implementation of recommendations to end gender-based violence and its harmful aftermath in the military. We need to implement reforms that are supported by data and input from key stakeholders, and we need to do so sooner rather than later.

Decades of research and anecdotal reports demonstrate that gender-based violence is prevalent and tolerated in military settings, that current policies and practices inhibit reporting and help-seeking, and that such violence contributes to poor mental health, premature separation and especially attrition of women from military service. This is unacceptable. We have the evidence. We need action.

Melissa E. Dichter, Ph.D, MSW, associate professor, Temple University School of Social Work.

Gala True, PhD, associate professor of research, Louisiana State University School of Medicine.

Glenna Tinney, MSW ACSW, DCSW, retired Navy captain.

Melissa Dichter and Gala True are scholars of gender-based violence and experiences of military service members and veterans who have conducted numerous studies in this area. Glenna Tinny is a retired Navy captain and social worker, working to end family violence and gender-based violence in the military.

Editor’s note: This is an op-ed and as such, the opinions expressed are those of the author. If you would like to respond, or have an editorial of your own you would like to submit, please contact Military Times managing editor Howard Altman, haltman@militarytimes.com.