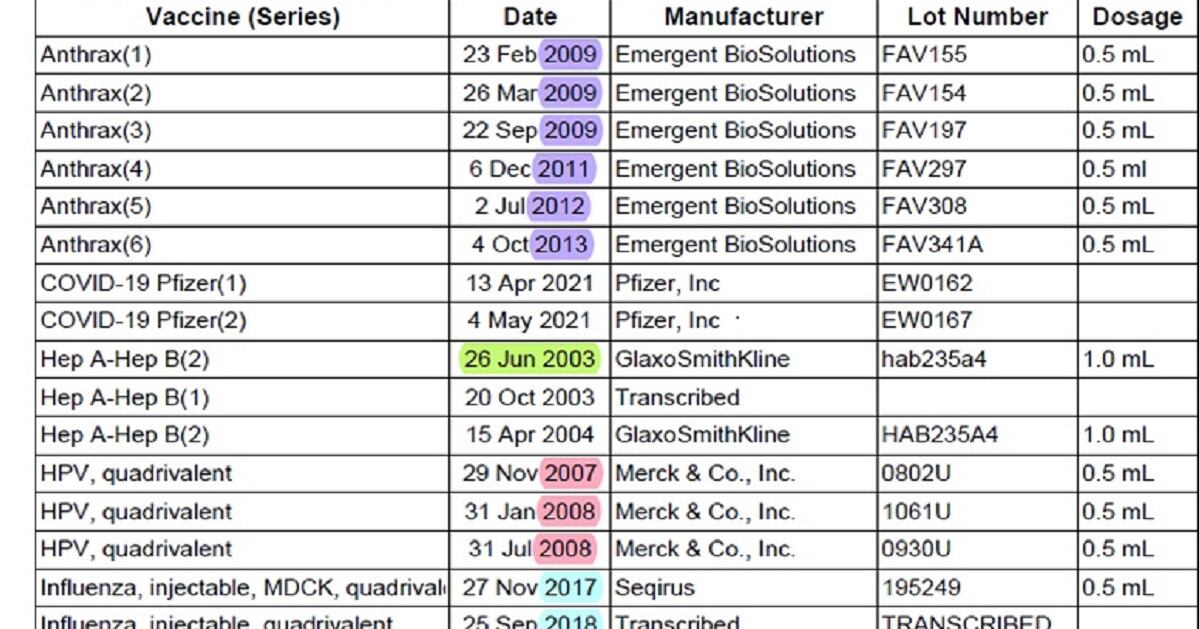

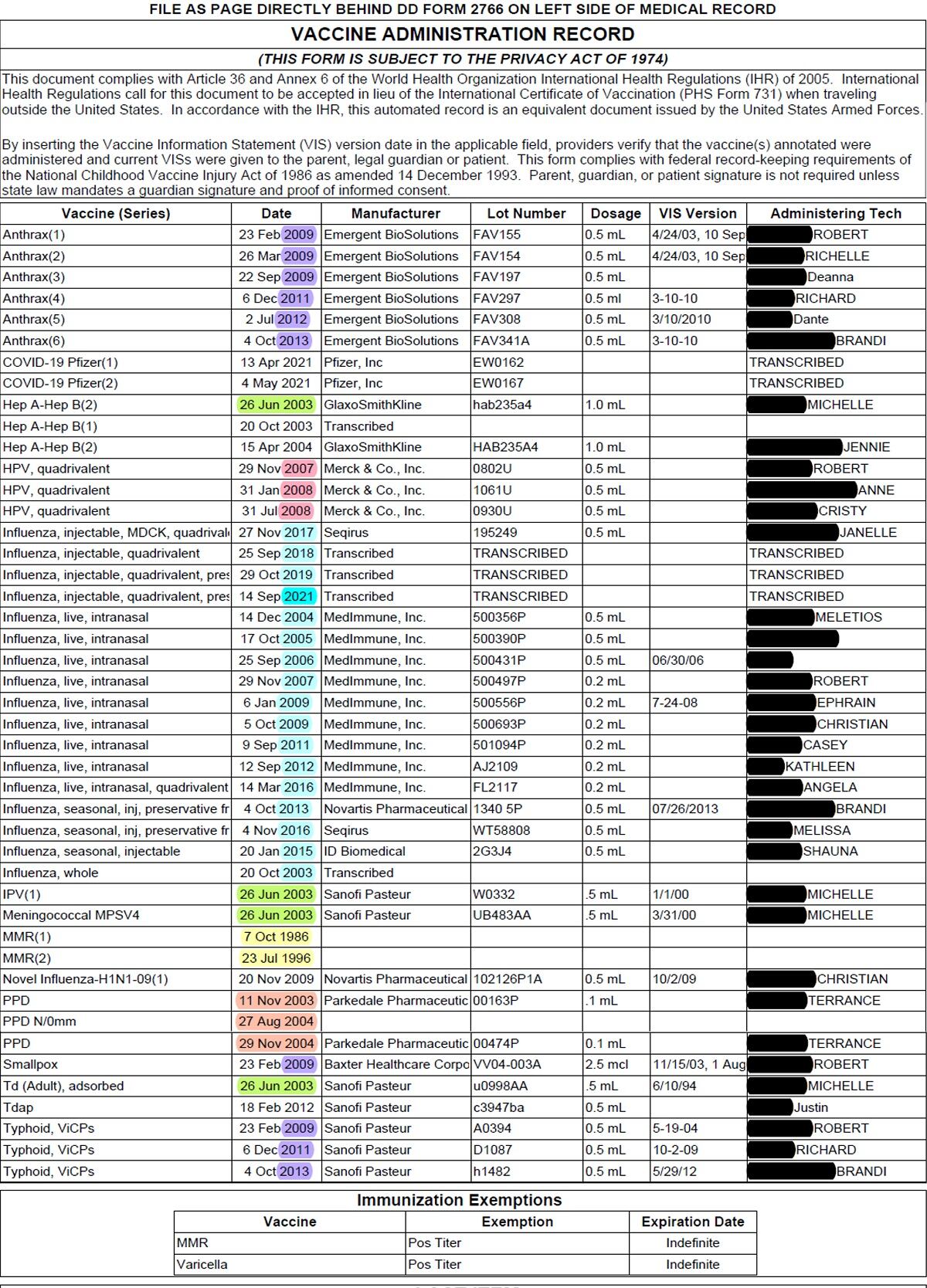

It’s immune system week in my Air Force Academy biology class. I project a document on the screen: my official immunizations record. Using just this table, can my students tell me: What day did I enter the Academy?

It doesn’t take them long to figure out I entered June 26, 2003. The give‑away? My record shows four shots that day, more than any other single day on my chart. Servicemembers remember, no matter what decade we joined, the infamous immunizations gauntlet we braved, T‑shirt sleeves rolled up, to the “thwoop! thwoop! thwoop! thwoop!” cadence of needles jabbing our anticipatory deltoids.

Our vaccine records say a lot about us. What else does mine say?

“Dig deeper,” I press, “what other predictions can you make?” Their first inquiry is inevitable, a half‑smirking accusation: “Did you get your flu shot every year?” Kindly note that every year, gruff sergeants across the military remind their troops — via increasingly threatening emails — that flu shots are very serious and very important.

Was I ever on the first sergeant’s naughty list? Yes … probably. I have a solid, early‑in‑the‑season compliance record from 2003‑2007 (thank you, conflict‑avoidant, rule‑following youth). In the 2008 season, I dallied until after the new year, and for 2010, I didn’t have a shot at all (I was off being an irresponsible graduate student in Boulder, Colorado — I blame the granola). Since then, I’ve gotten a flu shot each season (despite some wee tardiness or if, say, I lost my paperwork during the great COVID embarrassment that was 2020). Sorry, first sergeant.

Perhaps my vaccine record hints that I’m not the most consistent person in the world, but I’m working on it. What else does it say about me? I prompt my students with an easy question — who can estimate my birthday? The data points here are quickly spotted — the only shots administered in the 1980s. I got my measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) series in October 1986 and again in 1996. When was I born? Most students guess October 1985, which makes sense using today’s guidance. Since the early 90s, the CDC has recommended MMR at 12 months, but in the early‑mid 80s, the MMR vaccine schedule generally started at 15‑18 months, so re‑calibrating their hypothesis yields a better approximation. I was born in spring 1985. Good sleuthing!

Here’s another age‑based puzzle: How come I didn’t get the HPV vaccine until 2007? Targeted for pre‑teens and teens, shouldn’t I have had it a decade prior? Or on academy in‑processing day, if the government was so het up about it? Maybe this was the “botched” HPV vaccine roll‑out I’ve heard so much about. Savvier detectives recall Gardasil’s first approval by the FDA in summer 2006, so my 3‑dose regimen starting in fall 2007 actually makes me a relatively early adopter. That vaccine campaign must have been pretty effective, after all.

Next, I tell my students I’ve deployed three times — but which years? They surmise my first in 2009 with ease. My glut of anthrax doses and smallpox inoculation suggest these young Sherlocks change their address to 221b Baker Street immediately. But when else? Look further down my record, I suggest. I got a typhoid shot each time I prepared for travel to an at‑risk region. We conclude I went downrange in early 2009, 2012 and 2014.

Finally, I hazard a tougher exercise: What are all those “PPDs” about? The fastest Googlers report that “purified protein derivative” tests for tuberculosis. Good! But why test here in the U.S.? We’ve just learned about endemic diseases, I think, please make the connection! They do. Tb isn’t endemic in the States, but it is elsewhere in the world, and it spreads when people travel. Great! So, why the August and November tests? Tuberculosis peaks in spring.! My international students, more practiced at thinking globally, piece the puzzle together. “It’s spring in the southern hemisphere?” they propose. Bingo. Cadets’ vacationing in the global south is a reasonable (ultimately correct) explanation for the strange trend of autumn Tb scares in the cadet population.

Our vaccination records can tell us when we were born, where we lived, where we traveled, what the state of the world was, our attitudes toward health and civic duty. This year, my record shows I got the COVID vaccine — just one in a long line of preventive health efforts — as quickly and responsibly as I could. It shows that epidemiological research has protected me since before I could make decisions for myself. It even shows that sometimes I need to be prodded or reminded to take advantage of the medical privileges I’m afforded as the beneficiary of a robust, industrialized, affluent, evidence‑based institution.

Our vaccine records aren’t just personal stories; they’re stories about our communities — about how far we’ll go to protect each other.

What’s your vaccine story?

Rachel Reynolds is a lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Air Force; her career has taken her from tactical cyber operations to teaching biology at the Air Force Academy, to studying national intelligence and military strategy. She is currently a public policy PhD student at the University of Texas at Austin’s LBJ School and would like her first sergeant to know she has gotten her flu shot. All statements of fact, analysis or opinion are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Air Force, the Department of Defense or the U.S. government.