With less than three months to go before the year-end deadline, only one in six service members who are eligible to make the choice to opt in to the new military retirement system have done so, falling far short of prior expectations and raising questions about why the response has been so low.

About 1.6 million active-duty and reserve troops are eligible to opt into the new retirement system, which promises a smaller pension check for those who complete a 20-year career but offers cash payments into a personal retirement account that service members can keep regardless of how long they stay in the military.

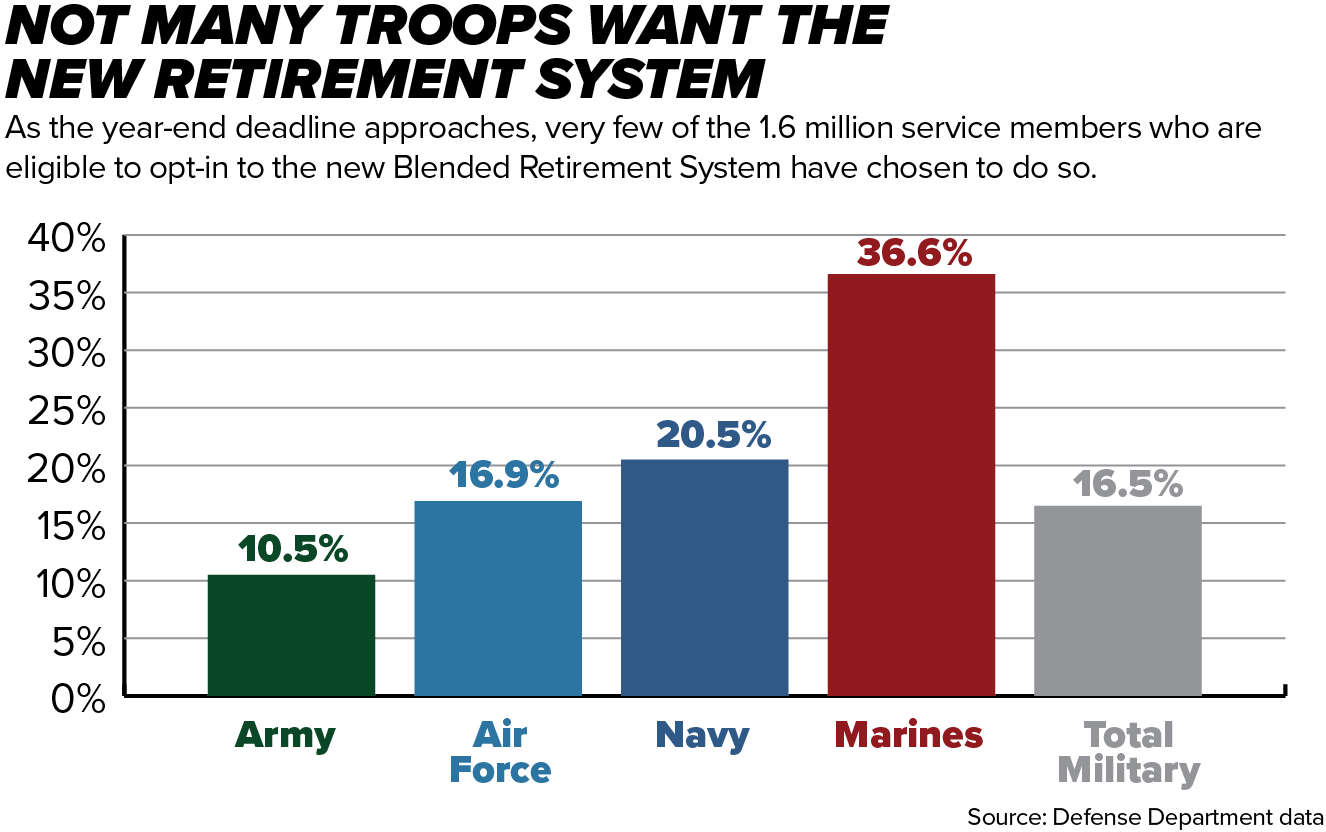

As of the end of September, 16.5 percent of those eligible service members have opted in to the Blended Retirement System, also known as the BRS, according to defense officials. The deadline for eligible service members to opt in to BRS is Dec. 31.

Yet within the individual military services, the response has varied significantly. The Marines have the highest opt-in rate, with 36.6 percent opting in to BRS. They’ve continued the trend from earlier this year. More than a third of the service members who opted in to BRS since July are Marines — the smallest service.

The service with the lowest percentage of enrollment is the Army, at 10.5 percent of eligible soldiers opting in. To date, 20.5 percent of sailors have opted in, and 16.9 percent of airmen.

The numbers are raising two basic questions: Are people just procrastinating in making their decision? Or are they affirmatively choosing not to opt into the BRS?

“It’s a really important question for someone to figure out what’s going on,” said Beth Asch, a senior economist at RAND specializing in defense manpower and compensation issues who has done extensive research and analysis on the BRS.

A 2015 law fundamentally changed the traditional retirement system for all future service members. Yet for troops who were in uniform at the time the law was changed, they now get a choice whether to keep the legacy benefit or to enroll in the new system.

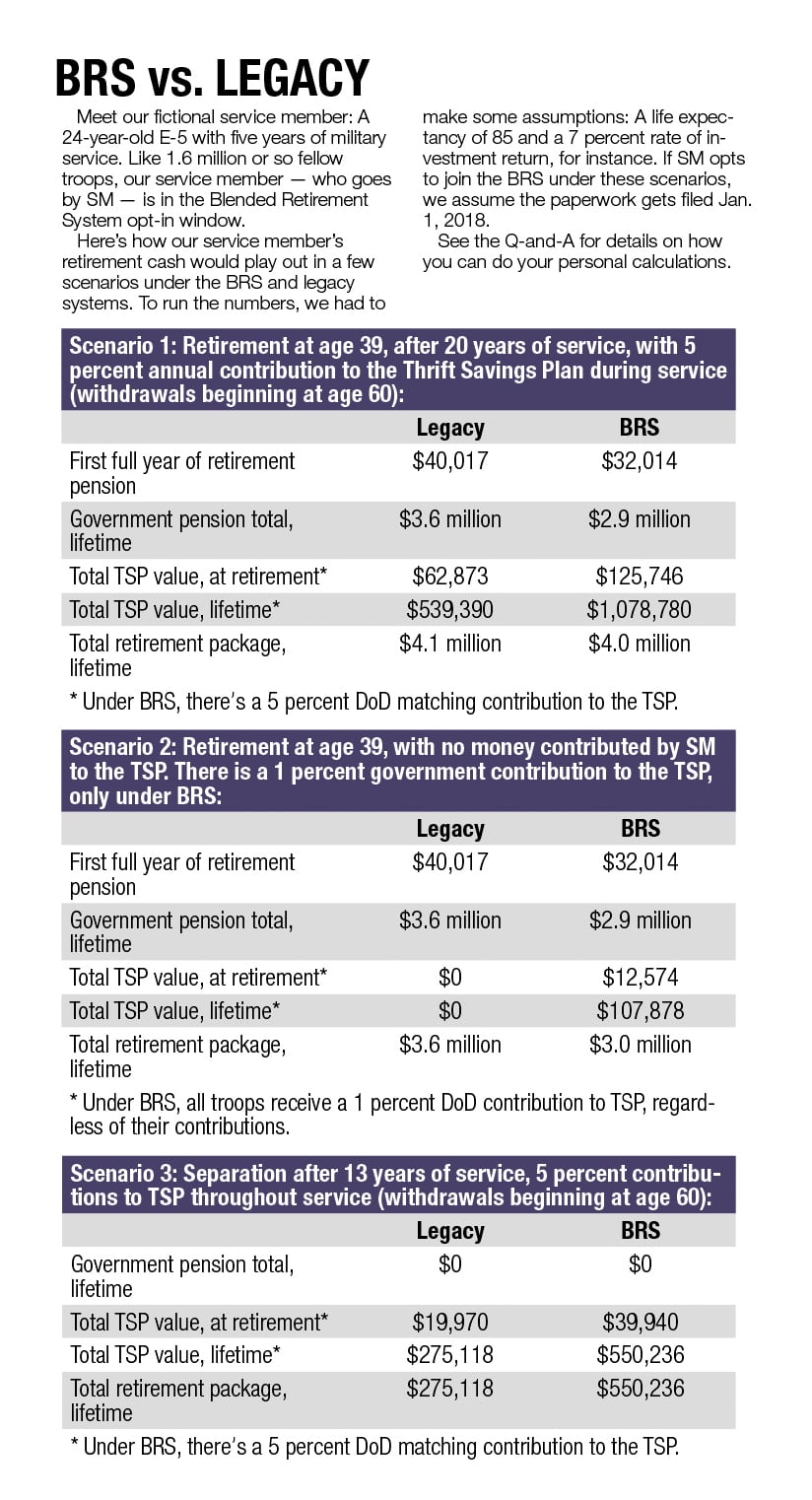

The traditional retirement system might be better for troops who will definitely complete a 20-year career because the pension checks will be higher. But for younger service members who may decide to leave the military before the 20-year mark — and would get no retirement benefit at all under the traditional system — the new system might be better because it will allow them to accrue some money in a retirement savings account that they can keep.

The retirement savings is accrued in a Thrift Savings Plan, or TSP.

All troops entering the military starting in 2018 are automatically enrolled into the new Blended Retirement System. But those with fewer than 12 years of service as of the end of 2017 can make the choice in 2018 to either stay with the legacy system or switch to the new BRS.

The Army, Navy and Air Force don’t require their service members to take any steps if they’re going to stay with the legacy retirement system. If they do nothing, service members will automatically remain enrolled in the traditional retirement system. But in order to choose the BRS, they must actively take the steps to opt in and fill out paperwork stating that intent.

The Marine Corps is the only service that requires its members to register their decisions regardless of whether they opt in to the BRS or stay with the legacy system.

Of the nearly 176,00 Marines eligible to make the choice, 54 percent have done so. Of those Marines, about 30,200 have explicitly decided to remain with the legacy retirement system, or about 17 percent of the total Marines eligible to make the choice. (They can also change their minds and opt in to BRS by Dec. 31.)

Some are puzzled why more service members haven’t opted in — especially younger enlisted troops with only a few years in the military.

“I’m a little surprised that the take rate isn’t higher,” said Stephen Pietropaoli, a retired Navy rear admiral who is chief operating officer for Navy Mutual.

Pietropaoli’s speculation is that most people just haven’t decided.

“You have to actually sit down and apply some mental energy to do an assessment, an analysis,” of life goals, expectations of being able to continue their military career, their personal finances, and what they’re trading for the portable TSP package, Pietropaoli said.

“When you give them a whole year to decide, a lot of them will take the whole year,” he said. "But there’s also the possibility that many will miss the deadline for opting in, and there will be dissatisfaction. ... That’s what I think the services should be worried about.”

He said it might help if the other services follow the Marine Corps example: requiring eligible service members to register their decision, whether they are opting in or staying in the legacy system.

Pentagon officials take a neutral stance, and have said they have no target or goal for opt-in, and no preference for which system individual service members choose. Each decision is an individual one, based on the service member’s circumstances and future plans.

For more than two years, the Defense Department and the services have been conducting a financial education campaign to inform service members about the features of the new plan, and questions to consider as they compare the features with the legacy plan. That includes a tool that allows service members to plug in their particular numbers and compare the results for staying in the legacy system, and moving to the new system.

“As we move into the final stage of the opt-in period, [DoD] is continuing its aggressive communications strategy,” said DoD spokeswoman Air Force Maj. Carla Gleason. “This awareness campaign incorporates social media, the Armed Forces Network, direct communications, and local installation commands,” she said.

RELATED

Those who are eligible to opt in to the new BRS or stay with the legacy system are active-duty members who had fewer than 12 years of service ― and reserve-component members in a paid status with fewer than 4,320 retirement points ― as of Dec. 31, 2017.

Those with more time in the military automatically stay with the legacy system; those entering on or after Jan.1, 2018, are automatically enrolled in the BRS. For more information, click here.

In their research for DoD on the effects of the BRS on retention, RAND Corporation researchers have estimated that virtually all junior enlisted personnel in the pool of people eligible to choose would elect the BRS over the legacy system, as would many personnel who are more senior. The election rate would drop off for those with more years of service.

“I think the bottom line is that fewer enlisted personnel, especially, are opting in than we would have expected,” said RAND’s Asch.

“When we do our analysis, we assume people have perfect information, in the sense that they fully understand all the nuances of the plan,” Asch said. “They may not have perfect information about the future, but they understand the plan and they act rationally on it. … They understand the features of it and what it means financially.”

Retirement may not be on the radar for many young, enlisted personnel, which is why the financial education is particularly important, Asch said. “It could be that they didn’t understand the financial education. … Maybe the education could be improved, although it’s my sense that it’s a very good program."

“The big question is: why are people leaving money on the table? My thought is that they may be getting advice that’s not necessarily in their best interest,” she said.

One hypothesis, she said, is that the young troops are looking to others for help in making their decision ― parents, and others around them who are older. “It’s not something most people know about, the pros and cons of the BRS."

“The thing that makes it tricky is that the decision that’s best for a 30- or 40- or 50-year-old is different than what’s best for a 20- or 25-year-old. … If the influencers tend to be older, they might be giving advice based on their experience, and where they are in their life cycle, and how close they are to retirement, which may not be necessarily in the best interest of the young member.

“One of the huge advantages of this program is that it’s particularly advantageous for young people who don’t think they’re going to make it to retirement. In fact, we know that most people will not make it to retirement, especially enlisted,” she said.

RELATED

According to the Defense Department, currently 81 percent of service members in the legacy retirement system separate with no government retirement benefit. Under the legacy system, only those who stay until they’re eligible for retirement can receive retirement pay.

Asch said she is neutral on the question of whether or not people should opt in, from the standpoint of DoD force management.

“But people could be missing out on an opportunity," she said. “Does that mean that everyone should opt in? No. But the fact that we have junior enlisted not opting in, is a shame. …

“The people who choose not to opt in who are young … I’m not talking about people who have 10 years of service. I’m talking about people with two, three years of service, and are choosing not to opt in, are leaving money on the table, because most of them will not make it to retirement. …

“They’re going to leave without any benefit, whereas if they opt in, they’d leave with something.”

Under the new BRS, the retirement pay is reduced by 20 percent for those who stay until they’re eligible for retirement benefits. However, DoD automatically contributes at least 1 percent to the BRS service member’s Thrift Savings Plan, and matches up to 5 percent of the service member’s contributions to his or her TSP. In addition, at the 12-year mark BRS service members receive a one-time payout of continuation pay— active-duty members get 2.5 times their monthly basic pay. Also, BRS service members who stay long enough to qualify for retirement benefits can opt for a partial lump-sum payout.

The DoD contributions to the TSP and other BRS features are not available to those in the legacy system.

Karen has covered military families, quality of life and consumer issues for Military Times for more than 30 years, and is co-author of a chapter on media coverage of military families in the book "A Battle Plan for Supporting Military Families." She previously worked for newspapers in Guam, Norfolk, Jacksonville, Fla., and Athens, Ga.