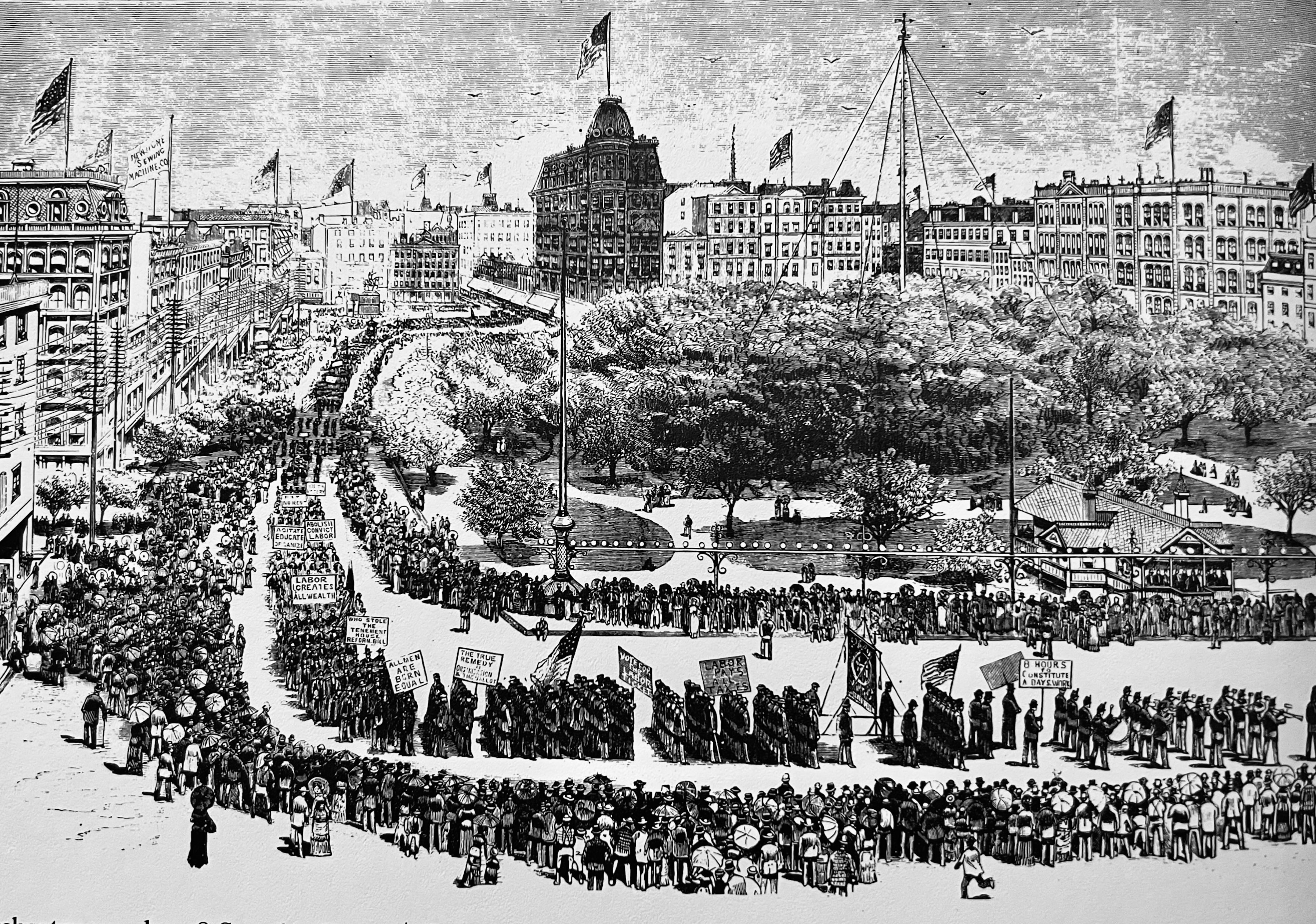

The first official historical celebration of Labor Day was in New York City on Sept. 5, 1882, with huge parades and picnics.

While the Big Apple was first to keep the party going, it might not have been the first to party; New York was not the first state to throw a parade. Pennsylvania and Rhode Island beat New York to the festivities, but due to lack of continuation over the years, these are not considered the first Labor Day parades.

New York wasn’t even the first state to sign Labor Day into legislation, a title which Oregon proudly claimed when it made Labor Day an official holiday in 1887. During that same year, Colorado, Massachusetts, New Jersey and New York state all passed similar laws. Over the following decade, Connecticut, Pennsylvania and Nebraska joined in.

Americans today embrace Labor Day as a last hurrah of summer, though the origins and the meaning of the holiday are less well-known, and not without controversy.

Starting in 1884, the labor movement called for strikes and protests on May 1 to push for an eight-hour workday. In 1889, International Workers’ Day, also known as May Day, was created by socialists and trade unions in Europe as a commemoration of the general strike for an eight-hour work day on May 1, 1886, in Chicago that led to a deadly riot that left at least 11 dead and dozens injured.

“Why would a militant labor event in America affect the rest of the world when America was trying to avoid it?” said Scott Molloy, a former professor at the Labor Research Center at the University of Rhode Island. “Well, they did it because these were martyrs. These were people who gave their life to a larger issue. And that is the eight-hour day, better treatment, better wages, and so forth and so on.”

Labor Day not May Day

May Day, which recognizes the work of labored workers through a celebration of dancing, singing and the crowning of a “May Queen” to bring in the new season, is celebrated in more than 60 countries on May 1, though not in the U.S.

“The rest of the world, especially the industrialized world, celebrated May Day,” said Molloy, in an interview with Federal Times. “In Europe, the working class was much better organized and organized earlier than in the United States, they were also very militant, and they would often combine their labor experience and desires with radical and revolutionary movements.

“So that’s how it got seared into the American mind that May Day, a European holiday, was a dangerous thing,” he said. “In the popular mind, particularly among politicians, who didn’t want any part of that stuff, they avoided the use of May Day, and created Labor Day, as kind of an alternative, a more civilized way to get attention and make achievements [because] they didn’t want to be stamped with the Red Scare from another continent.”

U.S. President Grover Cleveland had misgivings about the Socialist origins of Worker’s Day and the pagan origins of May Day and therefore officially signed legislation on June 28, 1894 to make Labor Day a federal holiday celebrated the first Monday in September, 1894 — marking the end of individual state celebrations and the beginning of nationwide recognition.

But Cleveland did not do this out of support for the Labor Union, he did it out of fear of voters, according to Molloy.

Cleveland “was no friend of labor, per se. He was against what they call protectionism,” Molloy said. “And that had to do with tariffs and taxes on imported goods, usually from England. And what would happen is that these manufactured items would come get to America at a cheaper price, and we could produce them. And so a lot of the labor unions would embrace the idea of a tariff to keep foreign made goods out ... So in an attempt to maybe get some of those votes back, he signed the law, establishing Labor Day on a federal basis. But in reality, I think 35 or 37 states had already passed legislation to celebrate Labor Day, so in many ways, Cleveland was the last guy in line, and he really didn’t do much.”

McGuire vs Maguire

Although the date of the first Labor Day is easy to pinpoint, there’s some debate over who the official founder of Labor Day was, but Peter J. McGuire and Matthew Maguire have been deemed the two men who stick out in history.

There are records from 1882 showing McGuire, the general secretary of the Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners and a co-founder of the American Federation of Labor, said that there should be a day set aside for a “general holiday for the laboring classes” that should be “celebrated by a street parade, which would publicly show the strength and esprit de corps of the trade and labor organizations.”

The New Jersey Historical Society believes that Maguire’s leadership of several strikes in the 1870s, with the intent of gaining recognition for manufacturing workers, should be credited with the foundership. They also found that while serving as secretary of the Central Labor Union, Maguire proposed the holiday in 1882.

No matter which McGuire-Maguire founded it, the right to celebrate the work of American citizens throughout history was a long fight in the making.

More than 140 years since the first Labor Day, Americans still celebrate the holiday with parades, barbecues and last-minute beach trips before the start of fall. And many recognize it as the informal end of summer.

Labor Day is recognized by 97% of employers by giving at least some of their employees the day off. However, this does not mean that everyone gets the day off.

In a survey conducted by Bloomberg BNA, 15% of organizations will have security, public safety workers or technical personnel working on Labor Day, 13% of organizations will have professional employees working, 11% will have managers working and 10% will have service, maintenance staff, sales and customer service working.

Federal employees will have Monday, Sept. 4, 2023, off of work and government offices will be closed.

The next federal holiday is Columbus Day.

Georgina DiNardo is an editorial fellow for Military Times and Defense News and a recent graduate of American University, specializing in journalism, psychology, and photography in Washington, D.C.