Air Force veteran Cindy Robison doesn’t get overwhelmed when she sees individuals with coronavirus coming into the health center where she is working as an emergency volunteer.

But she does when entire families come in sick.

“And it’s so many families,” said Robison, a former military nurse who is now working with Team Rubicon in northeast Arizona. “We just admitted two parents the other day and had to spend hours figuring out what to do with their five children.

“It’s bad, and it feels like it’s going to get worse.”

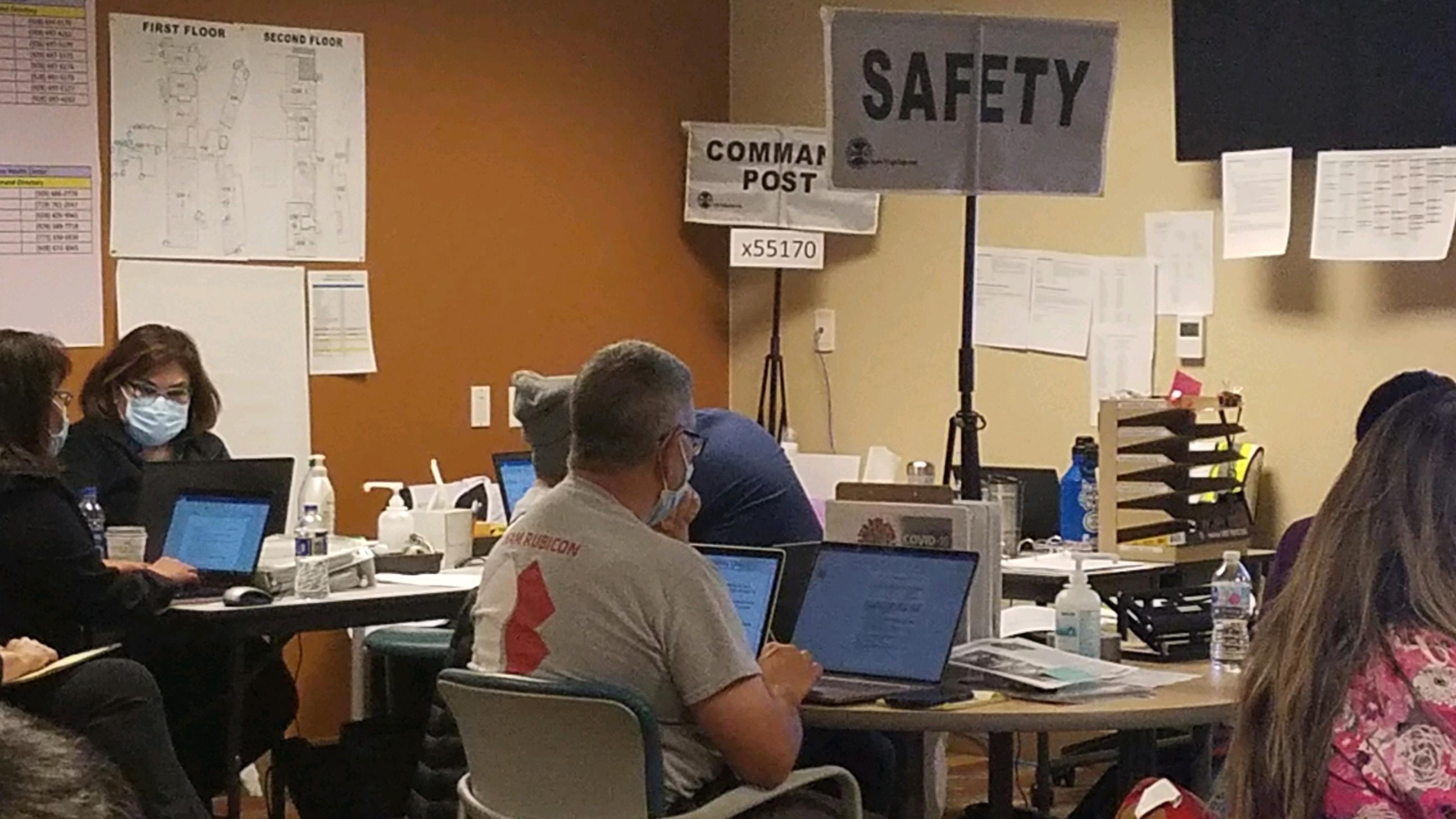

Robison is part of a team of about a dozen Team Rubicon volunteers helping staff the Kayenta Health Center in the heart of Navajo Nation, one of the hardest hit areas in the United States by the ongoing coronavirus pandemic.

RELATED

Volunteers from veteran-lead disaster recovery charity are accustomed to seeing scenes of destruction and heartbreak in their work. A few months ago, Robinson was part of a larger team of volunteers working in Texas to repair hurricane-damaged homes, sometimes performing grueling physical labor for hours on end.

But Scott Nargis, a former Army sergeant and coordinator for the group, said this deployment is different because of the invisible, ongoing threat the volunteers are facing.

“We’re used to working chainsaws and hammers for 12 hours and then getting ready for the next day,” he said. “Here, helping out with hospital operations, it’s 24-7. There’s no time at all to pull everyone together. And even if there was, we’re keeping our people isolated when they’re off shift.

“So it’s a different feeling for all of us.”

Even before the coronavirus outbreak, staff at the health center (one of five serving an area about the size of West Virginia) was overworked and fatigued from one of the worst winter flu seasons in recent memory.

So when dozens of new patients began pouring through the medical center’s doors with symptoms of the fast-spreading illness, Nargis said, the worry was that the clinic’s staff couldn’t safely keep up with the need.

“It’s an area with a lot of multi-generational families and some more vulnerable populations,” he said. “So this can spread quickly.”

Local officials have reported more than 1,200 cases among a population in the region of about 250,000 individuals, many living in rural conditions without reliable access to running water or outside information about the illness.

“They closed down some water stations, so some of these families have to drive for an hour and a half to fill up barrels of water for their homes,” Robison said. “When we tell them to wash their hands more to avoid spreading the virus, that’s less water they have to drink.”

Robison, who spent 23 years in the military as a nurse at domestic and overseas sites, said the volunteer work has been a rewarding return to medicine for her after several years not working directly with patients.

But, she adds, “it’s just so sad.” The number of coronavirus patients keeps climbing. The health center has had to fly several of the more seriously ill patients to a Phoenix hospital several hours away because closer clinics have no available beds.

“When I got here, my feeling was ‘I’m in good health, this is no big deal.’ But now I’ve seen people pretty young getting hit hard,” she said. “I know it’s in the rooms where we’re working. But you still want to help people.”

RELATED

The group is coordinating with federal authorities to make sure they and other hospital staff have enough personal protective equipment. Leaders have also been monitoring for signs of burnout, given the intense pace of operations.

But even when their deployment ends, the impact on the volunteers isn’t over. That’s because each one has agreed to a two-week self quarantine upon return home, in case they were exposed to the virus.

Robison said she is set to leave this weekend, but she won’t be returning home to Colorado. A friend who had been watching her dog is there now — if Robison is carrying the virus, even a quick interaction between the two of them could mean serious health risks for him.

“So I’m not sure what I’ll do for the next two weeks,” she said. “I’ve got a sleeping bag with a grill and and a cooler in my car. Maybe I’ll go camping for a little bit, and then start looking for the next volunteer opportunity.”

Leo covers Congress, Veterans Affairs and the White House for Military Times. He has covered Washington, D.C. since 2004, focusing on military personnel and veterans policies. His work has earned numerous honors, including a 2009 Polk award, a 2010 National Headliner Award, the IAVA Leadership in Journalism award and the VFW News Media award.