A retired Army colonel and his former West Point roommate believe they have discovered a nearly forgotten — and possibly first — Black unit in the Civil War and are spearheading efforts to see the history-making soldiers honored nearly 160 years later.

The career soldiers-turned-amateur-historians, retired Col. Chris Allen and retired Lt. Gen. Ben Hodges, former commander of U.S. Army Europe, say the members of the 1st South Carolina Volunteers of African Descent could be the first Black soldiers to wear Union uniforms, perhaps a year before the famed 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, which was profiled in the acclaimed 1989 film “Glory.”

Allen and Hodges presented their findings during a Jan. 27 virtual presentation for the Army Heritage Center Foundation titled, “The Union’s First Black Regiment and the U.S. Army’s Linkage to the Emancipation Proclamation.”

The two are spearheading efforts to see the unit’s role put in proper historical context for future U.S. Military Academy cadets, Army soldiers and the general public.

More than a mere footnote, the officers see this lost history as a way to further celebrate the role of Black service in the Army. These first soldiers were freed slaves, and some of the leaders with whom they fought were West Point graduates.

Some of their efforts include:

♦ Purchasing a headstone and placing a historical marker for the unit’s color sergeant, Prince Rivers, at his gravesite in Columbia, South Carolina;

♦ Further researching the post-war history of the unit’s members, Improving artifacts of the unit currently held at West Point;

♦ Working with the South Carolina congressional delegation to declare a day of recognition for the unit;

♦ Building a monument in Beaufort, South Carolina;

♦ Establishing exhibits at the Pentagon and the International African American Museum;

♦ Developing a case study for leader development courses in military officer programs.

♦ Establishing an annual commemoration of the unit at its former camp site by the U.S. Army Recruiting Command.

Army Times talked with Allen and Hodges before the presentation about how they came upon the story of the 1st SCVAD and their work to see the unit recognized.

Shortly after Allen retired in 2009 he moved to Beaufort, South Carolina, and a few years later, he bumped into the story of the 1st SCVAD by accident, he said.

He was visiting Naval Hospital Beaufort and while walking the grounds came upon a sign so small he almost missed it.

Labeled “Emancipation Oak,” the sign shared in a few sentences the history of the 1st SCVAD.

It told how the unit had formed in Hilton Head, South Carolina, in May 1862 and how its members had gone into combat in August 1862 before receiving their colors, more than four months before a reading of the Emancipation Proclamation at the spot of the marker on Jan. 1, 1863.

That was also nearly a full year before other Black units formed or even begun recruiting.

“I said, ‘No way, it cannot be true,’” Allen said. “They must have transposed a number.”

He shared his findings with his friend, even taking Hodges to the Emancipation Tree to see the historic site tucked away in an almost hidden corner.

Both Allen and Hodges say their knowledge of such Civil War units mostly comes from a few history classes and the movie “Glory,” decades ago. They emphasize that in this effort they are amateur historians simply trying to share what they’ve found.

But Allen did know that the 54th Massachusetts hadn’t started recruiting until February 1863. He decided to do some research.

What he found was as inspiring a story of Black history in the Army as he could have imagined.

On Nov. 7, 1861, a Union Navy-Army task force seized and occupied “Port Royal,” a deep-water port adjacent to what is now Marine Corps Recruit Depot Parris Island, South Carolina, as part of the Union blockade of the Confederacy. All of the whites living in the area fled, abandoning an estimated 10,000 slaves.

Army Maj. Gen. Thomas W. Sherman was left to manage the slaves, at that time labeled “human contraband” due to their slave status. By April 1862, Army leaders had requested equipment for a Black regiment, initiating the “Port Royal Experiment” that would see former slaves take arms against Confederates.

On May 8, 1862, the first 150 “contraband” volunteers enlisted at Hilton Head, South Carolina. Two months later, in July, Congress passed the Militia Act of 1862, authorizing black armed service.

On Aug. 5, 1862, Brig. Gen. Rufus Saxton deployed to the Georgia-Florida region with Company A, 1st SCVAD, and the company conducted the first Black unit combat operations on St. Simons Island.

Later that month the First Kansas Volunteers began forming and later mustered in early 1863. That’s where Allen believes some historical quibbling might emerge from his findings, because the official mustering is what is often used for unit histories and placing such events in a historical context.

He has not found details showing a documented “muster” of the 1st SCVAD as a regiment. In part, Allen and Hodges believe that’s because a lot of the SCVAD’s work was experimental, and, even in the North, arming freed slaves was somewhat controversial, so it wasn’t widely publicized.

Detailed histories of the unit are more difficult to find because many of the former slaves were prohibited by law from learning to read and write, while free men in the North and Kansas often sent letters home recounting their lives in uniform.

Also, the 1st SCVAD was formed at the beginning of the war, deep in enemy territory. As they formed, they were fighting.

But Col. Thomas Wentworth Higginson, a white officer in command of the regiment, wrote in his 1869 book, “Army Life in a Black Regiment,” that the 1st SCVAD can rightfully claim its place as the first Black regiment “that ever bore arms in defence of freedom on the continent of America.”

“...[M]y regiment was unquestionably the first mustered into service of the United States,” he wrote. He listed Nov. 7, 1862, as unit’s muster date, but it followed Company A’s combat experience in August of that year.

As the war progressed, bureaucracy also buried some of the story. More colored units were raised and deployed, and as part of a reorganization of the growing number of Black troops, the 1st SCVAD was reflagged as the 33rd U.S. Colored Troops, which it staked until shortly after the end of the war when it was disbanded along with many other units in 1866.

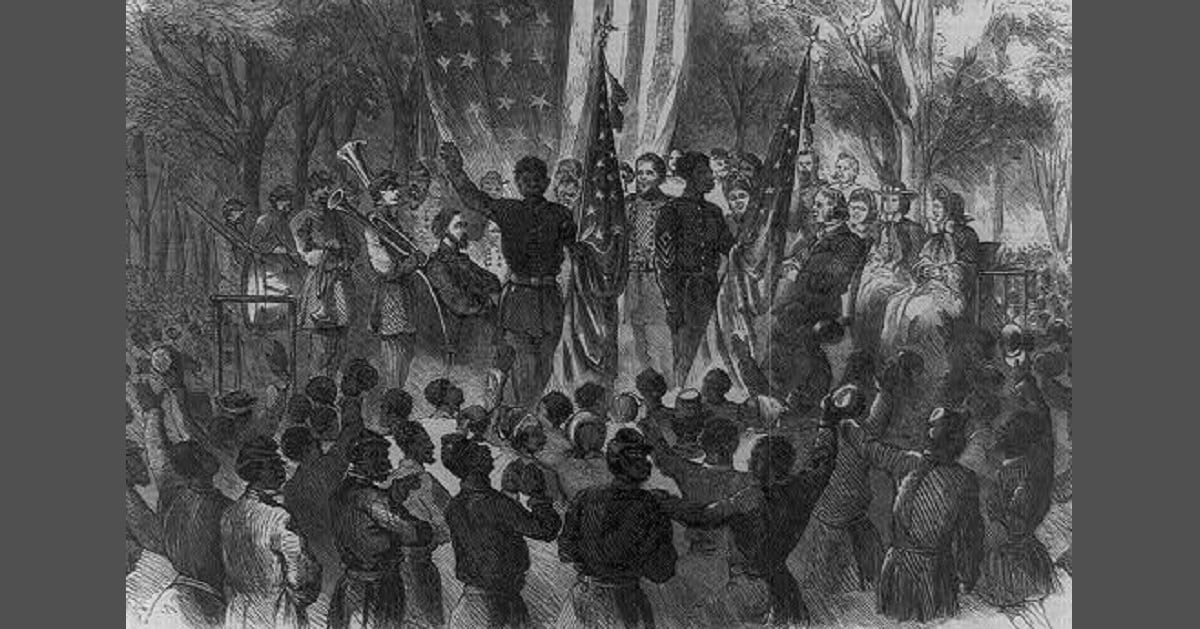

Further official oversight caused more damage when, in 1929, an Army board determined the 1st SCVAD Regimental Colors had no historic value and they were then destroyed. But, in 1988, artifacts from the 1st SCVAD’s Emancipation Day Ceremony were discovered in the West Point Museum, where they remain preserved.

Todd South has written about crime, courts, government and the military for multiple publications since 2004 and was named a 2014 Pulitzer finalist for a co-written project on witness intimidation. Todd is a Marine veteran of the Iraq War.