Image 0 of 5

As children at Patrick Air Force Base in the early 1980s, Kristen Emery and her siblings fished Florida’s Banana River and strung their catch on the back porch to eat. They dug up the backyard, muddying their hands. When they were thirsty, they drank tap water at their base housing.

Kristen’s nose bled all the time. She was in and out of the emergency room constantly with asthma or other illnesses from kindergarten through second grade.

“They just thought I was a sick kid,” Emery, now 41, says.

When puberty hit at 13, a large mass grew on her neck. The diagnosis was terrifying: Hodgkin’s lymphoma. She spent her teenage years in chemotherapy.

Then they found a tumor on her brother. A trip to the Mayo Clinic found it to be benign.

“I went through all of this, this hell — as a 13-year-old girl in junior high and going through high school. Everybody else was worried about going to prom and stuff, I was worried about dying and losing my hair and being sick. I could get a cold, and it could kill me, literally. Hodgkin’s destroys your immune system,” she said.

The family moved on to their next assignment, at Peterson Air Force Base in Colorado. Emery’s grandmother stayed at Cocoa Beach, near Patrick.

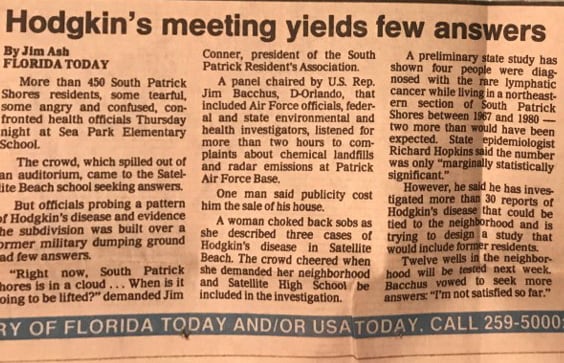

In 1991, after Emery’s diagnosis, her grandmother started mailing her newspaper articles.

In all, the tiny neighborhood by Patrick in 1991 discovered at least 12 cases of Hodgkin’s tied to people who had lived there between 1967 and 1983. The Orlando Sentinel called the cases “an unusually high incidence” of the extremely rare cancer, which affects about 8,500 people in the United States each year, according to the American Cancer Society.

A local furor erupted with the discovery. But it died down just as fast.

Federal agencies that tested the soil and water reported there were no contaminants. An “Air Force team of experts found no unusual rates [of illness] … at the base hospital.”

“All the sudden, it just kind of went away,” Emery recalled. “They said, ‘Nope, there’s absolutely no way this is connected.’ It got shut down, and we don’t hear anything about it. Until now, it’s starting to come back up again.”

RELATED

In April, Military Times reported that the Pentagon had, for the first time, released a full study on military installations where it has found higher-than-recommended levels of cancer-causing perflourinated compounds ― perfluorooctane sulfonate or perfluorooctanoic acid, commonly referred to as PFOS or PFOA ― in either the base water drinking systems or groundwater. Patrick Air Force Base was one of the bases identified.

The results were grave enough to prompt military officials to take mitigation efforts that have included closing some water wells, handing out bottled water and installing filters on base housing water taps, according to the report.

The danger of these chemicals is now widely understood, prompting the Pentagon study. PFOA and PFOS exposure has been tied to multiple types of cancers, developmental delays in fetuses and infants, and more.

The contaminants are found in everyday items such as Teflon and some 3M products. Yet the military community may be more at risk because the chemicals are also concentrated in the foam the military uses to put out aircraft fires.

These toxins are among those contributing to the almost $30 billion of environmental cleanup responsibilities that DoD has identified at its active and closed military bases.

Many military families are, of course, already worried about the long-term health implications.

Those concerns intensified on May 15 when Politico broke the story that senior officials in the White House and EPA had blocked the publication of a Health and Human Services study of PFOS and PFOA water contamination around military bases, a draft of which was set for release for public comment.

Citing emails it had obtained, the news outlet reported that the “study would show that the chemicals endanger human health at a far lower level than EPA has previously called safe.”

The draft release was blocked because officials thought it would be a “public relations nightmare,” Politico reported.

Family cancers

After the Military Times published an April article about toxins found on military bases, about a dozen families contacted the Military Times with similar tales: service members or spouses who were battling cancer. Multiple instances of autism or other developmental issues in their kids. And a suspicion that the rate of health issues in their military neighborhoods seems too high to be just a coincidence.

“I worked for Fort Monmouth [Army base] and my daughter was born with a defect and, in fact, several others also had children born with issues …” one person wrote.

Another wrote: “Both my wife and several friends had cancer, several have passe[d] away, and I have an autistic son.”

When Emery found the story, it hit like a rock. After she beat Hodgkin’s in her teens, she went on to serve eight years in the military as an Army medic with the 82nd Airborne Division. She separated from the service in 2004 with the rank of sergeant.

Emery married a fellow soldier and gave birth to a daughter with chromosomal abnormalities.

After she read the piece, she wrote in.

“It just angers me that there’s a lot of questions as far as the long-term effects” of potential exposure, she said. “The more that we can do studies on it, and the more we can stop denying that it’s happening and own up to it,” the better chance everyone has of being protected in the future, she said.

Emery also thinks it’s more than just coincidence that many military families have health issues. After she separated from the Army, she became a civilian paramedic. Emery said she could always tell when their ambulance was near a military installation “because there’s so many Down syndromes and different types of birth defects.”

RELATED

Last week, Sen. Jeanne Shaheen, D-N.H., put out a letter with her colleagues demanding release of the HHS study first reported by Politco. Her district includes the former Pease Air Force Base, which is contaminated. She has also introduced legislation to establish a registry for military families to report cancers and other illnesses that may be tied to PFOS or PFOA exposure, similar to the registry the VA has set up for burn pit exposure.

“It is unacceptable and irresponsible that release of this study has been blocked,” Shaheen wrote. “Families who have been exposed to emerging contaminants deserve to know about any potential health impacts.”

In a statement to Military Times, the Department of Health and Human Services’s Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry said the unreleased draft study includes a toxicological profile of the sites and will include new recommendations on the minimum levels of exposure to PFOAs or PFOS that “a person can eat, drink, or breathe each day without a detectable risk to health.”

“The body of knowledge about [the compounds] is emerging quickly,” the agency said. “We are working with the EPA, DoD and other federal partners to provide consistent and proper interpretation of the role of [minimum recommended levels] and how they should be used and interpreted.”

There is not a new date yet for the draft study’s release for public comment, the agency said.

The firefighter

Paul Cyman knows the contaminants well. The former Air Force sergeant served as a military firefighter from 1969 to 1973, and deployed to Vietnam from 1971 to 1972.

“I was exposed to both types of foams,” Cyman said.

In his first years of service, the military was using a protein foam to put out fires. But the foam “was a corrosive chemical,” Cyman said. “It plugged up the lines and required a lot of flushing.”

In 1970 the Air Force switched to a different foam — aqueous film-forming foam, or AFFF, which has the PFOS and PFOA contaminants.

Stateside and in Vietnam, Cyman had a protective suit to handle the chemicals. But when it was hot and the firefighters were just doing training, they routinely ditched the gear.

“We wore the asbestos-type suits, with the hood, and we had the gloves … but if you were using the chemical just for exercises, then it wasn’t necessarily that you had the equipment on all the time,” Cyman said.

“After the training exercise was done, you had to do cleanup. You’ve got to roll up all your hoses. You’ve got to drain them, flush them and hang them to dry. And, of course, you’re handling all that stuff all the time. And if it’s an extremely warm day out, of course you’re going to take that heavy asbestos coat off, the hood, and, of course, the heavy gloves. And you may just have your boots and pants on.”

That cleanup also involved clearing all the excess foam.

“It was just draining into whatever drains were around,” Cyman said. “It would go into the storm drains. There was no containment at all.”

Cyman has three children; his oldest has dyslexia and other learning disabilities; his youngest is autistic. In 2017, Cyman peed blood. Doctors diagnosed bladder cancer.

Cyman is grateful bladder cancer is considered highly treatable. He was able to have the tumor removed this January, but will need continued medical visits for at least the next two years while doctors check for any new tumors.

When Cyman saw the Military Times article in April, the first thing he looked at was the accompanying photo. It showed two airmen from the New Jersey Air National Guard 177th Fighter Wing battling a simulated aircraft fire in June.

“I thought, ‘Jeez, they are still using that same stuff. I thought that maybe there was something better that came along.’ ”

The services are in the process of substituting replacement foams that contain fewer harmful chemicals. The Air Force, for example, is replacing its stockpiles of AFFF with Phos-Chek 3 percent, which it said reduces PFOS/PFOA exposure.

As the base contamination issue gets more scrutiny, Cyman would like to know what DoD knew about the foam when they first put it into his hands.

“Why would you put something out there like that, or have us use it … when you didn’t do more research on it?” he said. “So you either knew about it, and put it in our hands anyway, or you didn’t do enough to study it to see what its effects would be before you put it into use.”

Tara Copp is a Pentagon correspondent for the Associated Press. She was previously Pentagon bureau chief for Sightline Media Group.