The Pentagon got pulled into the debate over President Donald Trump’s controversial immigrant family separation policy earlier this year after the administration voiced plans to house detained children on American military bases.

No kids have been sent to the installations this summer, but if they do it won’t be the first time bases have sheltered undocumented immigrant kids detained near the border with Mexico.

RELATED

Nearly 16,000 minors ended up on military posts in California, New Mexico, Oklahoma and Texas between 2012 and 2017, according to a recent Congressional Research Service report.

Most of the detained juveniles came from Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador without their parents, according to the U.S. Department for Health and Human Services, which oversees the care of kids after U.S. Department of Homeland Security agents take them into custody.

Fort Bliss, an Army installation abutting the Texas border city of El Paso, housed 7,259 unaccompanied kids from September 2016 to February 2017, according to CRS. That time frame straddled the waning days of President Barack Obama’s White House and the early months of Trump’s administration.

The typical stay lasted 57 days, according to Health and Human Services spokesman Mark Weber.

RELATED

Lackland Air Force Base near San Antonio took in 800 kids from April 2012 to June 2012 and 4,357 kids from May to August of 2014, CRS found.

Fort Sill in Oklahoma hosted another 1,861 minors and California’s Naval Base Ventura County received 1,540 more in 2014, too.

And Holloman Air Force Base in New Mexico briefly held 129 juveniles in early 2016, CRS added.

Kids ended up on military bases between 2012 and 2016 because existing shelters were overwhelmed by the sheer number of children being detained along the border.

Tasked with caring for nearly 60,000 unaccompanied minors in 2014, Health and Human Services “ran out of room" and kids “were backed up in border facilities, which were not designated for children,” spokesman Weber said.

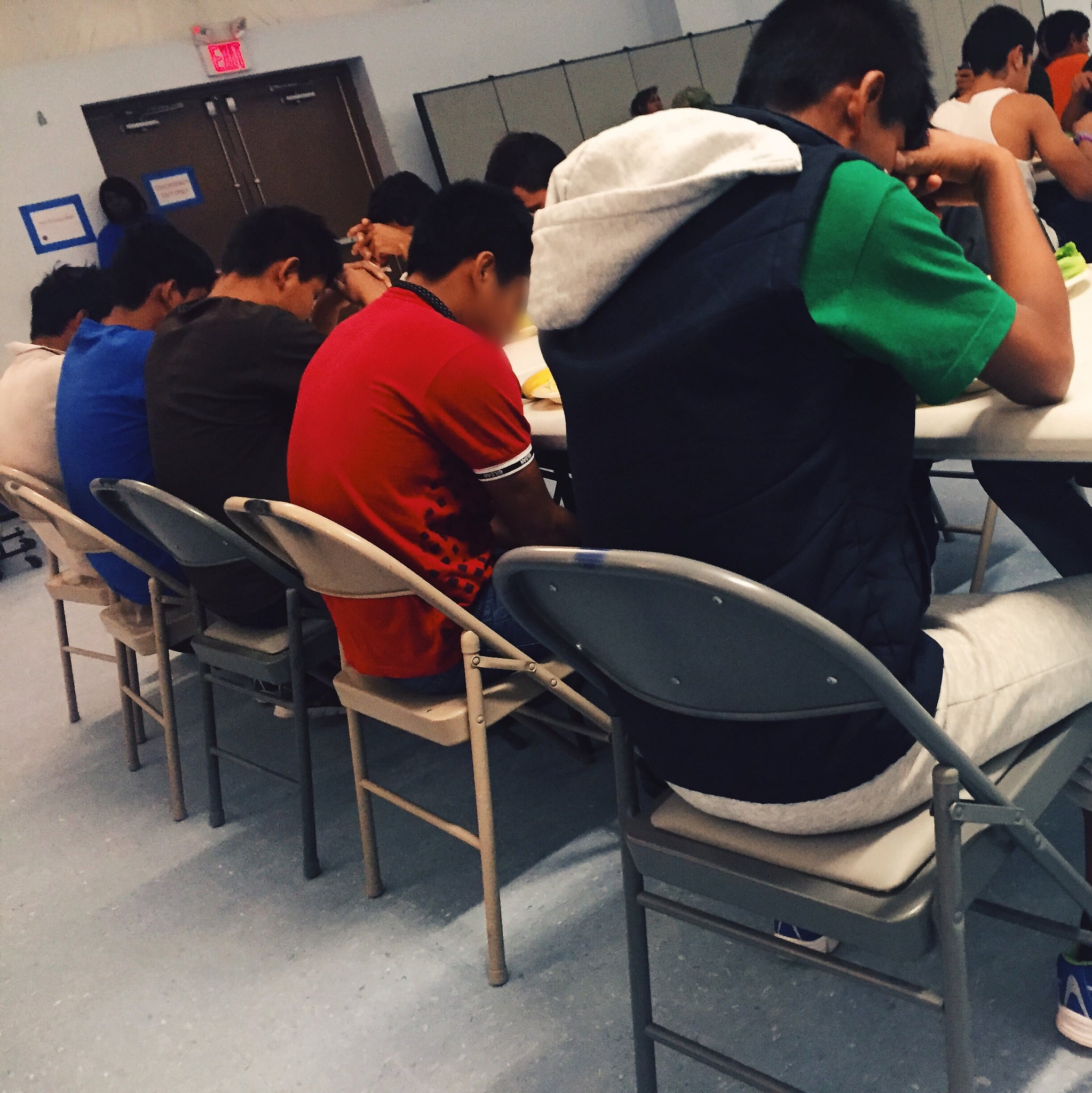

It was that influx that generated photos of youngsters sleeping behind fences and under silver-colored blankets, he said.

Those images spread through social media during this year’s debate and were erroneously attributed to Trump’s policies.

A key policy difference between the Obama and Trump administrations was the controversial decision by today’s White House to separate children from their families when they were detained together.

Before, that happened only “on very, very rare occasions,” usually when agents suspected the adults were dangerous criminals or weren’t the children’s real parents, Weber said.

Weber described the 50 buildings used to house youngsters at Bliss in 2016 as similar to “Quonset huts," with semi-permanent structures for classrooms and administrative centers erected near them.

Most of the minors were between the ages of 13 and 17 and Health and Human Services used about 50 acres of a training facility at Bliss to house them, Weber said.

Sprawling across 1.12 million acres, Bliss is larger than Rhode Island.

The military only provided space for lodging immigrants and no troops were diverted from their duties, according to Army Lt. Col. Jamie Davis, a Pentagon spokesman.

“HHS is responsible for all care of the children, including supervision, transportation, security, meals, clothing, and routine medical services,” Davis said. “No DoD civilian employees or military personnel would be involved in these services.”

The children were screened for medical conditions before they arrived at military bases and they were released to parents or suitable guardians after the adults were found and vetted, according to Health and Human Services.

Weber said only minors without significant health problems entered military installations.

If they got sick while there, they were transferred to providers contracted by the agency, not Defense Department hospitals.

A few children were injured while staying at Bliss, but Weber characterized those injuries as standard stuff for youngsters.

“There’s a couple soccer fields, kids would get hurt,” Weber said. “Things would happen when you have 2,000 kids.”

While Weber said his agency constantly works with the Pentagon to identify bases that could become emergency shelters for detained immigrants, no installations have been needed this summer.

If the number of juvenile detentions rise, however, bases could be activated and “kids would receive the same level of care as HHS has provided in the past," he said.

The practice of relying on military bases to absorb undocumented juveniles is different from 20th century practices, CRS found.

In those cases, the armed forces took in people fleeing war or dictatorships.

More than 4,000 ethnic Albanian refugees arrived at Fort Dix, New Jersey, in 1999 as ethnic warfare raged in the Balkans, according to CRS.

Another 25,000 Cuban refugees were housed at American bases from 1980 to 1982, after the Mariel boatlift crisis sent as many as 125,000 immigrants to Florida’s shores in 1980.

American military installations also took in nearly 51,000 Vietnamese, Laotian, Cambodian and Hmong refugees following the collapse of the Saigon and Phnom Penh governments in 1975.

Military Times reporter Tara Copp contributed to this report.

Geoff is the managing editor of Military Times, but he still loves writing stories. He covered Iraq and Afghanistan extensively and was a reporter at the Chicago Tribune. He welcomes any and all kinds of tips at geoffz@militarytimes.com.