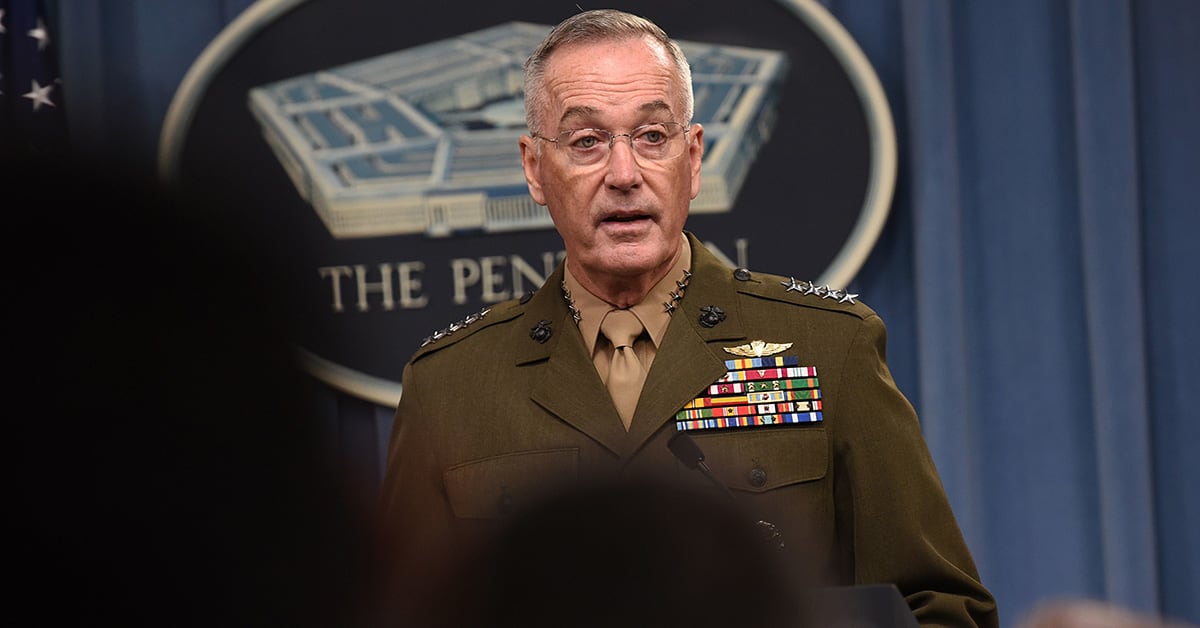

ISLAMABAD — Chairman of the Joint Chiefs Marine Corps Gen. Joseph Dunford and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo met with their Pakistani counterparts Wednesday to try to persuade Islamabad to do more against the terror networks operating within its borders.

The visit came amid rising tensions between Islamabad and Washington. The Trump administration’s South Asia Strategy depends heavily upon Pakistan going after Haqqani network and Taliban leaders who organize attacks on Afghans from inside Pakistan. As long as the attacks continue, Afghanistan may not stabilize to the point that a negotiated settlement is possible. That lack of stability and settlement is one of the key factors keeping U.S. forces in Afghanistan after 17 years of operating there.

“On the surface, they say they want to cooperate,” Dunford said ahead of the meeting. “On the surface they say they recognize that a peaceful solution in Afghanistan is the right approach. On the surface, they say they support an Afghan-owned, Afghan-led peace process, so what we’re looking for is actions to back that up.”

RELATED

“We need Pakistan to seriously engage to help us get to the reconciliation we need in Afghanistan,” Pompeo said to reporters traveling with him to Pakistan.

It was a historic first visit for both Dunford and Pompeo in their respective military and diplomatic roles, although Dunford has made numerous visits in his prior role as head of U.S. forces in Afghanistan.

RELATED

Without greater pressure from Pakistan, it will be difficult to get Afghanistan settlement talks underway, said Seth Jones, director of the transnational threats project at the Center for Strategic and International Security.

“I think the idea of settlement for the moment, especially as long as the Taliban’s command and control structure is untouched in Pakistan, I think they are unlikely to conduct serious negotiations in general,” Jones said. “I suspect they’re likely to continue to fight and give themselves better bargaining position for future negotiations of their own."

The Trump administration has become increasingly frustrated with Islamabad, and has withheld hundreds of millions of dollars in military assistance since last fall, including another $300 million last week in Coalition Support Funds.

“The rationale for them not getting the money is very clear,” Pompeo told reporters. “It’s that we haven’t seen the progress that we need to see from them.”

The cancelled aid raised the question of whether Pakistan would take retaliatory measures against the U.S., to include restricting access to two key ground shipping routes, commonly known as GLOCs, that the U.S. uses to ship supplies to forces in Afghanistan.

Dunford said he did not expect the GLOCs to be affected.

“I think they [the Pakistanis] understand the delicate situation we are in right now in our bilateral relationship and I wouldn’t expect that they will seek to make it worse,” Dunford said. “But we’ll see what happens.”

RELATED

Pakistan’s GLOCs are the least expensive way to deliver supplies to U.S. and NATO forces, and currently 40 to 50 percent of the supplies supporting the coalition still move through there. But the GLOCS are vulnerable to shifts in U.S.-Pakistan relations and were closed for months following a November 2011 NATO shooting incident along the Pakistani border.

The remainder of the supplies are either flown into Afghanistan directly or transit into Afghanistan through the northern route, a network of shipping and rail lines that moves goods from the Mediterranean Sea through Georgia, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan to Afghanistan’s Hairatan rail port.

The reliance on Pakistan to support a large force in Afghanistan keeps the U.S. from being as aggressive as needed to convince Pakistan to go after the militants, said Blackwater founder Erik Prince, who is pitching that the U.S. use a small contracted force in Afghanistan instead that wouldn’t need the GLOCs.

“We complain to Pakistan about the ISI, Haqqani network, all the rest,” Prince said. But “we can never apply that pressure … because they’ll just shut off the logistics flow.”

Jones said even if the U.S. applies additional pressure and stops relying upon the GLOCs, Pakistan may have already decided to go another way. For example, some of the aid cancelled last year froze the transfer of up to 16 AH-1Z Viper attack helicopters Pakistan had ordered from Amarillo, Texas-based Bell through the Foreign Military Sales program. Those helicopters still have not been transferred, and Jones said it may just shop elsewhere.

“Pakistan’s general response has been to move closer to Beijing,” Jones said. “To strengthen its relationship with Moscow, with any of the [weapons] systems that the U.S. provided, to try to make it up elsewhere.”

Tara Copp is a Pentagon correspondent for the Associated Press. She was previously Pentagon bureau chief for Sightline Media Group.