I opened my eyes. I knew I wasn’t dead, not yet, anyway. The world came into view. For a second, I thought the enemy had stopped firing at us. They hadn’t. We were all deaf from the RPG blast.[i] It had detonated two feet from my face. My left arm was burning. I looked down and saw what was left of it. It was blown off about midforearm. I could see my jagged, splintered bones jutting out from a bloody, scorched, flayed-open stump. I knew I had lost my left hand.

My right hand was killing me. I raised it up in front of my face to get a good look at it. It was blown off at the base of my hand. There were a few uneven bone fragments sticking out where my palm used to be. It looked as if some of the skin that used to be my hand was dangling, shredded to pieces like someone had removed all the bone and flesh from inside. It hung like an empty glove that had gone a few rounds with a garbage disposal. I thought, “Fuck, both of them!”

I wasn’t done assessing the situation, though. I looked down and saw that my left leg was blown wide open, my femur split in half like a jagged, splintered water hose. It pumped out huge amounts of blood with every heartbeat. Imagine a coffee cup full of blood, hot blood. Now imagine that every time your heart beats, you toss about that much blood out of your cup and down your thigh. The coffee cup would fill up again in between heartbeats. I knew I only had so many cups of coffee left in me.

My leg had almost been blown in half. I took one look at the gleaming white bone sticking out of a sea of red, and I knew I was dead if I didn’t stop that bleeding. How was I going to get a tourniquet on my leg and both arms when I didn’t have hands? The fight wasn’t over yet. I knew I needed to use my head.

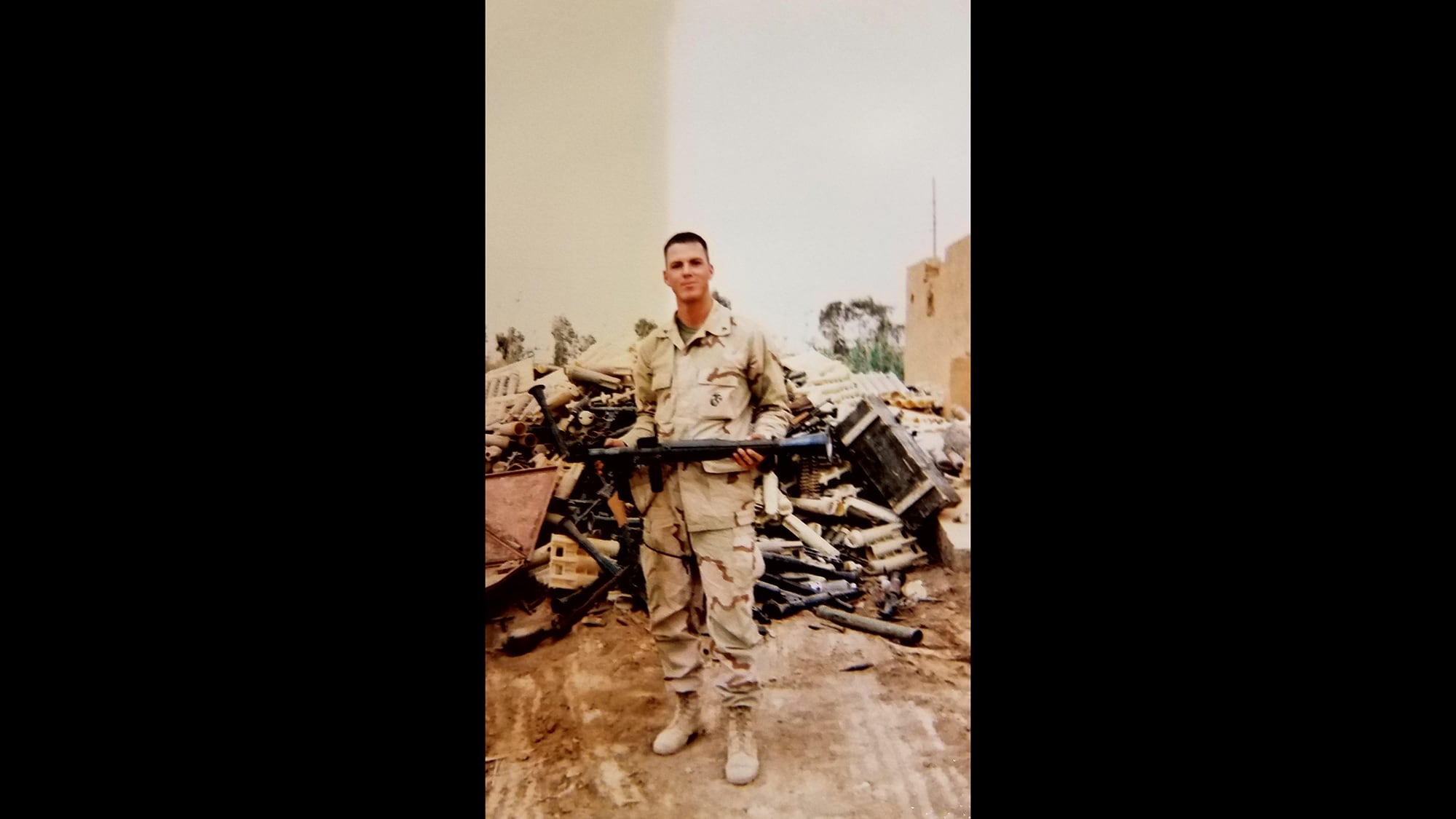

Trauma sucks. Even for combat veterans. I don’t think anyone would disagree. I do, however, think combat veterans have unique resiliency and fortitude to deal with trauma. Somewhere along the line, I feel America’s perspective changed towards combat-wounded veterans and the trauma we experienced. Where once we were venerated, now we are often pitied. I speak from personal experience. I was no stranger to war on the day that I lost my arms and nearly bled to death, in Fallujah, Iraq. I was injured during my second deployment to Iraq, having taken part in the invasion in 2003 prior to that. There wasn’t much I hadn’t seen or experienced by then.

I remember waking up in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) at the National Naval Medical Center (NNMC) Bethesda Maryland Hospital. I think the ICU staff thought I had sustained a serious head trauma because of my attitude. I was happy. Too happy. It didn’t make sense to them, and I don’t blame them for being confused. Hell, I used to tell my teammates that if I ever lost an arm or a leg, they should go ahead and put me out of my misery.

From the outside looking in, I should have been devastated. Both my hands were blown off completely. My left leg was wrapped in plastic, the tissue of my thigh and shin shredded to oblivion. Skin grafts were in the near future for me. No less than six suction tubes connected me to the wall. I could see my injuries, and I could remember every bit of the sights, sounds, and pain associated with taking a direct hit with an RPG. What a horrible thing for anyone to have to go through. Right? Yes, perhaps, if you allow yourself that perspective. But that’s not my perspective, and perspective is the hallmark of resilience.

The first time I met Doc Springer face-to-face was in Chicago. I was there to undergo a medical procedure called stellate ganglion block, a promising new treatment for symptoms of trauma. It had been fourteen years since I was wounded … fourteen years that weren’t easy. Recently, I had decided to man up and be the warrior I know I am. To me, this meant I had to finally work on my mental fitness with as much, if not more, effort than I had put into my physical fitness or any other discipline.

I am fortunate that in my journey towards improving my mindset and emotional well-being, a brother I served with introduced me to Doc Springer. I had seen firsthand how her approach had helped out my fellow combat veteran so much. That was enough for me personally to “vet” her, as we veterans like to do. Before I was wheeled back to the procedure room, I had a conversation with Doc Springer, who was bedside before, during, and after the procedure, providing overwatch like she does.

As I progressed through the procedure, we spoke about personal concerns of mine and of trauma. I explained to Doc Springer that what I struggled with daily was not the loss of my hands or the disability it implied. She nodded with a look of recognition and said to me, “I bet a lot of people assume that your biggest trauma, the one that has been the most challenging, is the loss of your arms, but I can see that that’s not the case for you. You’ve adapted and overcome in that area the way that Marines do. Your trauma is not what most people assume.” And this is the truth that many people — even people with advanced clinical training — cannot see.

What I struggled with was the trauma I had experienced throughout my entire life, not just my combat experience — least of all my combat wounds. By the time I got injured in Iraq, my trauma was already in place. And any trauma I sustained on the day I got hit by the RPG was far overshadowed by the pride I felt.

As I explained to Doc Springer, in becoming a Recon Marine, I felt like I had accomplished my greatest goal. I was part of an elite team of warriors. On that day in Iraq, despite life-threatening injuries, I acquitted myself honorably on the battlefield. I lost my hands as a true warrior. For myself, and so many other veterans, the term “hero” makes us feel awkward. What feels more awkward, though, is to hear that term book-ended in a conversation by pity.

Doc Springer doesn’t emit pity because she understands the warrior spirit at an instinctive level. She has a no-nonsense approach to treating or preventing PTS. She communicates that we are strong enough to overcome the challenges before us and that we can do this by using skills we possess already, whether we realize it or not.

Doc Springer’s new book “WARRIOR: How to Support Those Who Protect Us” is a book about the challenges we face, but make no mistake about Doc Springer’s approach. She doesn’t see us as broken. She calls to our strength and she walks with us in a way that translates like this: I see the challenges before you, and I can help you get clear on them as well. Now, get up and fight.

Sgt. Eddie Wright, USMC (retired),

Bravo Co. 2nd Plt. 1st Reconnaissance Bn.

OIF I, II

[i] Contrary to what many people believe, “RPG” does not actually stand for “rocket propelled grenade.” The abbreviation comes from the Russian phrase for handheld antitank grenade launcher, ruchnoi protivotankovye granatamyot.

Editor’s note: This is an Op-Ed and as such, the opinions expressed are those of the author. If you would like to respond, or have an editorial of your own you would like to submit, please contact Military Times managing editor Howard Altman, haltman@militarytimes.com.