After 20 long years, the war in Afghanistan is coming to a close. Yet what does the next chapter for the U.S. military look like?

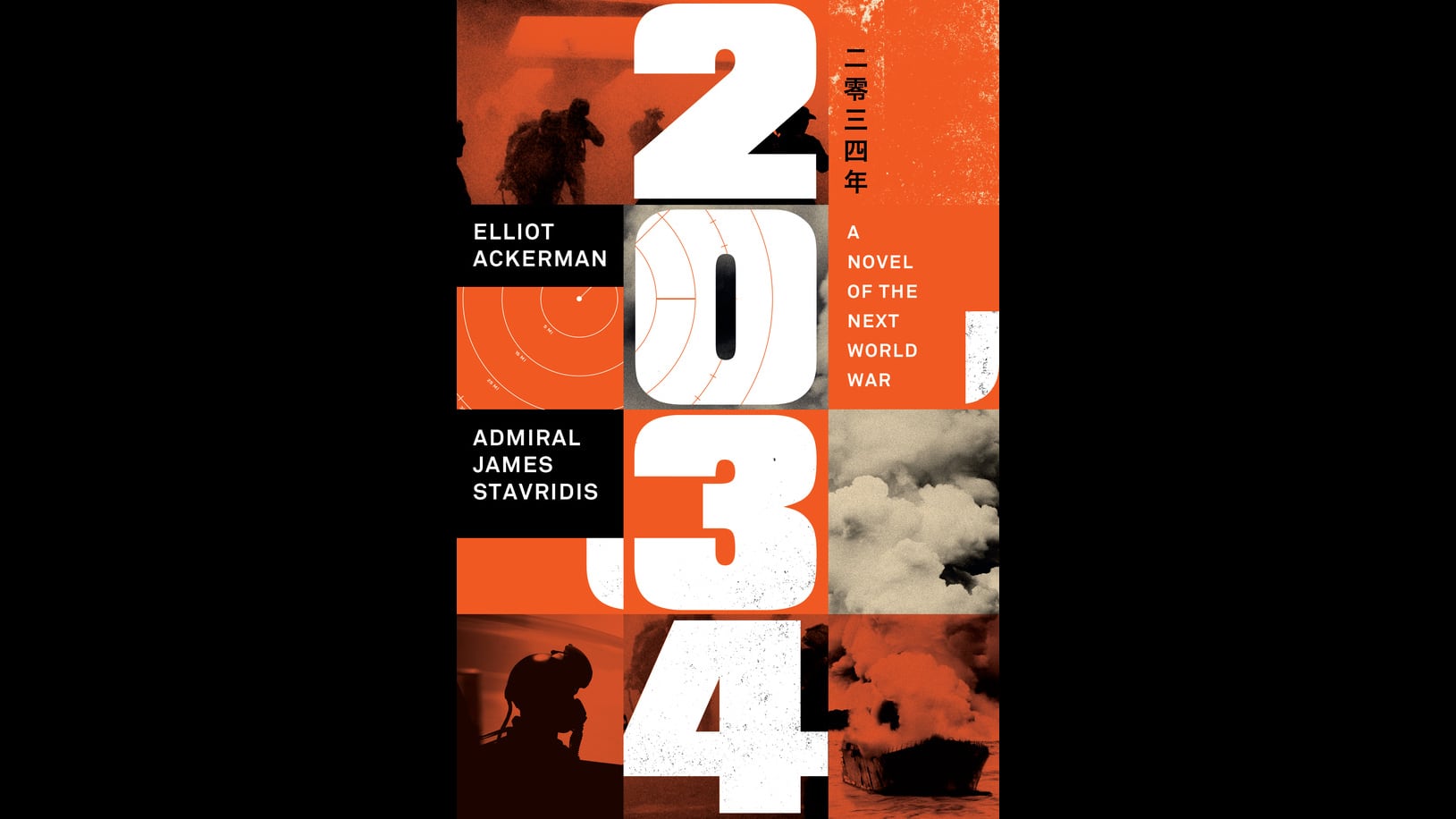

One projection involves an F-35 pilot shot down by Iran and a U.S. naval destroyer sunk by Beijing in the South China Sea. That is the fictional premise behind a new buzzed-about book, “2034.”

RELATED

The dismal prospects of how the U.S. military might fare in a future war, whether against China, Iran, or some other enemy, has Pentagon planners, defense manufacturers, and service chiefs bracing for a future that will not be kind to the defense budget. Besides ballooning national deficits, non-traditional national security priorities, and pushback against pricey yet unproven fighters like the F-35, the impact of COVID on the U.S. economy, two separate COVID relief packages, and the proposed “American Jobs Plan” could result in one of the biggest defense budget cuts in modern history.

This very real possibility has the armed services — the Army, Marine Corps, Navy, Air Force, and now Space Force — each scrambling for a larger piece of the dwindling pie. A U.S. Air Force general recently stated that the U.S. Army’s pursuit of long-range artillery and missiles capabilities was “stupid.” The Army has had to reassure the Marines that they aren’t trying to encroach on their efforts in the Indo-Pacific region.

Some services are better at crafting compelling fiscal narratives than others. As the late Congressman Ike Skelton shared with one of us in 2009, “Congress understands the strategic utility of a carrier strike group or a bomber wing. They have a harder time with an infantry brigade or an armor battalion.”

In the wake of the 2013 sequestration, a similar turf war broke out when the military was set to take a roughly $1 trillion cut to its budget. The Department of Defense conducted a controversial study that included a set of scenarios and potential conflicts. Behind closed doors, each service argued that their strengths would be the greatest contribution of winning and therefore should be prioritized in budget decisions. Clearly, none of the scenarios imagined in 2013 have happened.

Now with the news that the U.S. will pull its last troops out of Afghanistan in September, it is anybody’s guess where or how U.S. forces will be deployed next. One camp will argue that the next major war will take place on the high seas while another foresees a grand conflict waged across the skies using state-of-the-art manned and unmanned aircraft. Still another camp will insist that any future war must involve island-hopping campaigns in the South Pacific akin to World War II, while yet another will argue that the future portends clashes in outer space and the cyber domains. And some will simply tag every future concept with an appropriate military modifier (“cross-domain,” “multi-domain,” or “all-domain”) in hopes of maintaining an illusion of equity across the services.

The British military recently endured their own defense budget war. The end result, based on assumptions that other nations would bear the burden of future warfighting, was major cuts to military end strength and the smallest British army to take the field in 300 years.

Landpower, traditionally the domain of army forces, simply doesn’t share the same narrative appeal as technologically advanced — and often prohibitively expensive — platforms and capabilities. In an information age society, putting “boots on the ground” is increasingly viewed as unnecessary when other capabilities can achieve the same ends without the commitment of “blood and treasure.” When the budget strings tighten, armies tend to shrink.

But should they? For many landpower advocates, the answer to that question came in the aftermath of the Korean War. “You may fly over a land forever; you may bomb it, atomize it, pulverize it and wipe it clean of life,” remarked historian T.R. Fehrenbach in his 1964 book, “This Kind of War.” “[B]ut if you desire to defend it, protect it, and keep it for civilization, you must do this on the ground, the way the Roman legions did, by putting your young men into the mud.” The U.S. has a terrible history of cutting landpower after wars despite going into Korea and Vietnam with a depleted Army, it wasn’t until the 1980s that land forces were prepared for their next fight.

When deterrence fails, the introduction of significant ground forces signals an unmistakable level of national commitment and will. Although much has changed since the wars in Korea and Vietnam, one immutable fact remains: conflicts are decided in the land domain, where the will of the people ultimately rests. Any future conflict will inherently involve all the services, but without landpower — namely tanks and troops — to achieve a decisive outcome, we are likely to usher in an era of lengthy and inconclusive wars that are passed on to successive generations.

Don’t believe the made-in-Hollywood hoopla about drones or cyber deciding the next war. Being able to decisively take and hold territory — whether in Crimea or Taiwan or a sandy patch of the Middle East — is what matters. The rest is all sci-fi fantasy.

John Spencer is the chair of Urban Warfare Studies at the Modern War Institute at West Point. Steve Leonard is director of assessments at the University of Kansas School of Business.

Editor’s note: This is an op-ed and as such, the opinions expressed are those of the author. If you would like to respond, or have an editorial of your own you would like to submit, please contact Military Times managing editor Howard Altman, haltman@militarytimes.com.