It had been nearly five years since Winston Churchill had declared that “an iron curtain has descended across the continent,” and plunged the West in a Cold War and a hot race for armament with the East.

Yet worlds away from Washington and Moscow, in a remote outpost 40 miles west of Idaho Falls, Idaho, a town would soon become home to America’s first nuclear accident.

On Jan. 3, 1961, operators from the U.S. Army’s Stationary Lower Power Reactor One, or SL-1, were returning from a 10-day holiday break.

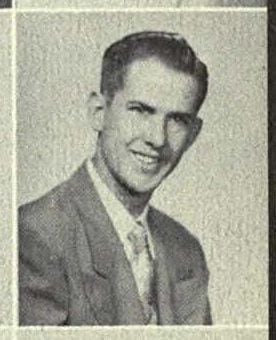

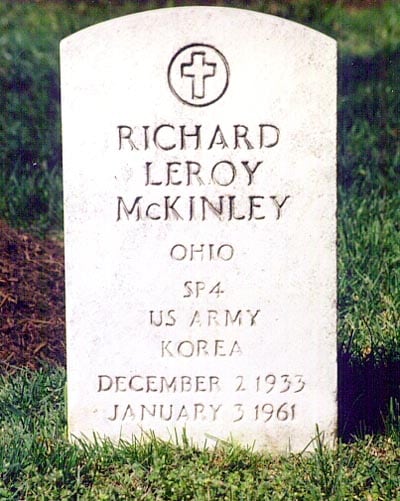

Among them was Army Spc. John Arthur Byrnes, Navy Seabee Richard Carlton Legg and SP4 Richard McKinley.

SL-1 was designed to provide heat and electricity for remote Defense Early Warning system radar sites, established to provide early warning of attack by Soviet aircraft or ICBMs, supplementing conventional plants requiring costly and hazardous diesel deliveries.

However, poor oversight, lack of rigorous training and detailed procedures and inadequately tested technology spelled disaster for SL-1 and its operators that night when, shortly after 9 p.m., a steam explosion blasted through the plant.

According to Argon Electronics, which provides nuclear and other hazardous material training simulators, the blast had enough force to lift the whole 26,000-pound apparatus over 9 feet into the air and create 500 pounds per square inch of pressure “which forced the plugs at the top of the reactor open and fire the control rods like missiles into the ceiling.”

“The entire reactor room was instantly filled with burning steam contaminated water and fragments of the radioactive cores,” Argon said.

It would take over an hour and a half for responders to arrive at the reactor, and when they did, they found dangerous levels of radiation.

Byrnes and Carlton were killed almost instantly in the blast. McKinley was still breathing, but the 27-year-old succumbed to his injuries shortly after being transported into an ambulance.

An Atomic Energy Commission investigation found the explosion had been caused by an operator pulling the reactor’s central rod too far out of its housing and, according to NASA, “This withdrawal caused the reactor to go ‘supercritical’ in just 4 milliseconds as the core power level surged to 20,000 megawatts or over 6,000 times the rated power output.”

It was speculated that the rod had become stuck, resulting in an operative accidentally pulling it too hard to free it. Others say it was the simply the result of human error.

Brynes and Legg were buried in their hometowns but McKinley, a Korean War veteran, was laid to rest at Arlington National Cemetery at the behest of his wife.

Twenty-two days after the explosion, McKinley’s family gathered in Arlington, Virginia, to watch the veteran’s eight-minute funeral — from 20 feet away.

Laid to rest in a double lead-lined casket, McKinley was lowered into a 10-foot-grave encased in concrete and surrounded by a metal vault. For good measure an additional foot of concrete was poured in atop his casket.

McKinley’s gravesite remains the only radioactive burial plot in Arlington National cemetery, and while it is safe to visit, his cemetery file warns, “Victim of nuclear accident. Body is contaminated with long-life radioactive isotopes. Under no circumstance will the body be removed from this location without prior approval of the AEC [Atomic Energy Commission] in consultation with this headquarters.”

Claire Barrett is an editor and military history correspondent for Military Times. She is also a World War II researcher with an unparalleled affinity for Sir Winston Churchill and Michigan football.