The U.S. Senate voted Tuesday to kill a bipartisan resolution to remove U.S. forces from the conflict in Yemen between a Saudi-led coalition and Houthi rebels, heeding Defense Secretary Jim Mattis’ warnings to drop the issue.

Sens. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., Mike Lee, R-Utah, and Chris Murphy, D-Conn., introduced the joint resolution to overrule the president’s deployment of forces using the War Powers Act. But the resolution was defeated on Tuesday afternoon by a vote of 55 to 44.

Sen. Bob Corker, R-Tenn., introduced the motion to table the resolution, which would have brought a “Wild West debate” onto the Senate floor, he said.

Corker instead argued that a new bill should be brought up through committee hearings where it can be “amended and dealt with in a more methodical and appropriate way.“

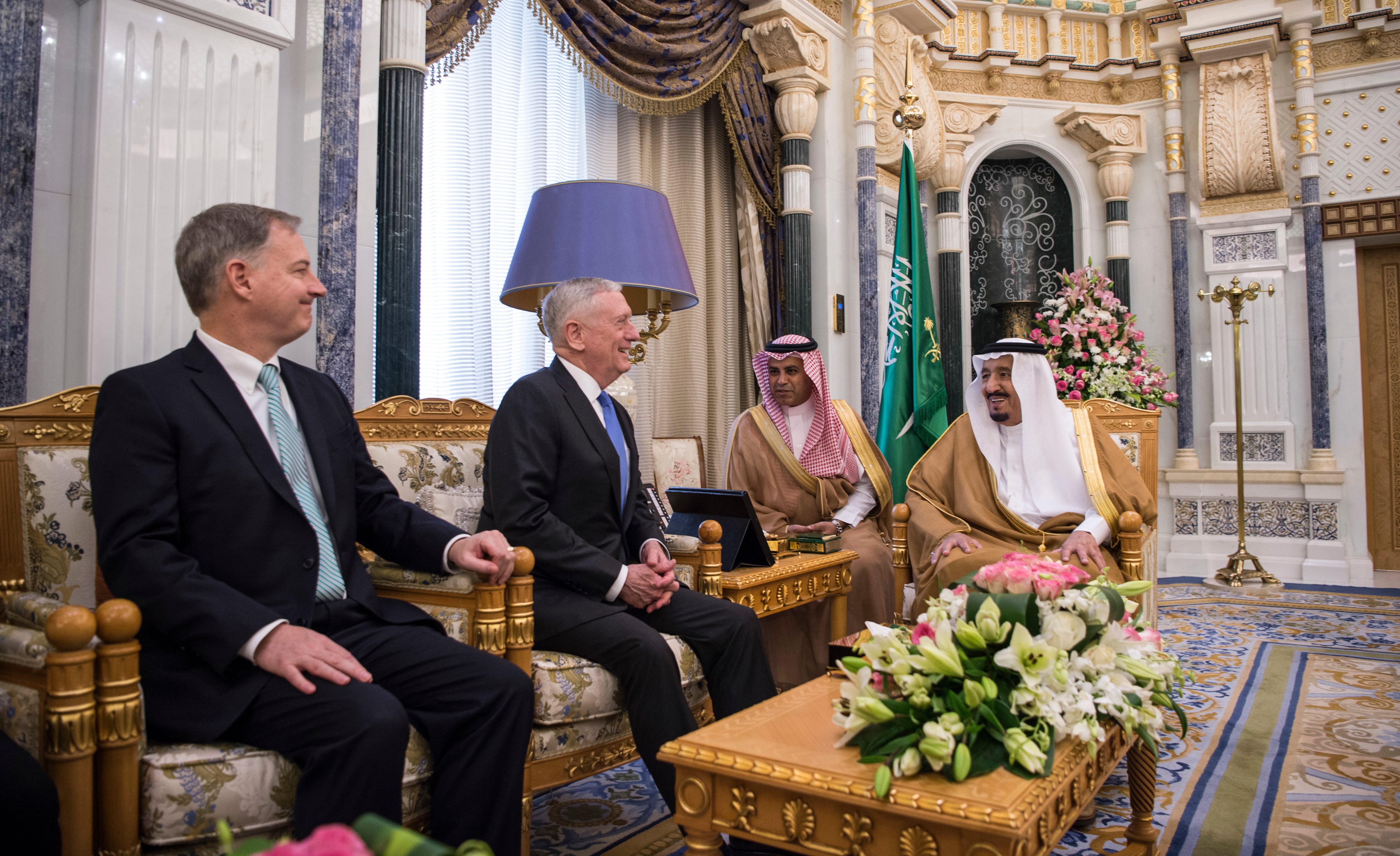

Corker seemed to be siding with Mattis, who earlier this month sent a letter stating flatly that the Defense Department “opposes this proposed resolution.”

However, “I welcome discussion of the situation in Yemen,” Mattis wrote. “[The] DoD shares your concern about the harm to Yemeni civilians and infrastructure.”

Despite the invitation for dialogue, Mattis cautioned abandoning the conflict altogether, writing that such action “could increase civilian casualties, jeopardize cooperation with our partners on counter-terrorism, and reduce our influence with the Saudis — all of which would further exacerbate the situation and humanitarian crisis.”

The United States’ role in Yemen

On one side of the Yemeni civil war are the Iranian-backed Houthi rebels, originally aligned with the ousted — and now deceased — former President Ali Abdullah Saleh.

On the other side is a Saudi-led coalition backing President Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi.

Thrown into the mix are factions like al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula and the Islamic State, each vying for a slice of the fractured country.

Since 2015, U.S. military support to the Saudi-led coalition has stuck to a non-combat role, according to Air Force Capt. AnnMarie Annicelli, a spokeswoman for Air Forces Central Command.

“In 2017, AFCENT deployed liaisons to Saudi Arabia to share best practices with the [Royal Saudi Air Force] and advise on how to mitigate civilian casualties by improving their planning, targeting and execution of air operations,” Annicelli said.

RELATED

Those liaisons assist the Saudis on best practices for their deliberate targeting process; “but liaisons are not involved in the specific selection of targets or prioritizing and matching responses for combat missions,” Annicelli added.

Consistent with U.S. law, existing agreements and regulations, the American liaisons may respond to Saudi requests for information about threats to Saudi border security, and associated threat networks, Annicelli explained.

Currently, there are roughly a half dozen U.S. service members serving as liaisons in the Saudi Air Operations Center in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, according to AFCENT.

Despite that, many more service members participate in other support roles, to include refueling of Saudi aircraft that do conduct kinetic strikes in Yemen.

“As of Jan 1, 2018, U.S. aerial refuelers have conducted more than 2,800 refueling operations and offloaded 88 million pounds of fuel in support of U.S. missions and Saudi and Emirate operations against threats throughout the Horn of Africa,” Annicelli said.

However, “we do not have a break out for specific refueling stats in support of just Saudi-led operations in Yemen,” she added.

Additionally, U.S. special operations forces have, within the past year, been involved in boots-on-the-ground raids in the country.

In one such military action, a U.S. Navy SEAL was killed and three others were wounded during a firefight at an al-Qaida compound in Yemen.

Operations like that, however, are against Islamic terror groups, which have been interpreted by both Democrat and Republican presidents as fair game under the Authorization to Use Military Force that Congress passed in 2001 to allow U.S. forces to go after al Qaeda and its affiliates.

"We're involved in a war against al-Qaida and ISIS in Yemen, but not against the Houthis," said James Phillips, a senior research fellow for Middle Eastern affairs at The Heritage Foundation.

"They're kind of overlapping wars, but as I understand it, the U.S. has been careful not to go over the line," he added.

RELATED

As far as the United States’ stance toward the Saudi-backed regime in Yemen, “that's the internationally recognized government,” Phillips said. “So I think we have a strong legal basis for cooperating with them in a limited capacity, like refueling Saudi and Emirate airplanes and providing intelligence."

That intelligence on targets does seem to mitigate the humanitarian crisis in Yemen, Phillips added.

"If they didn't have that intelligence, [the Saudis] would be more likely to just do general bombing," he said. "I think it's a good thing because it helps the Saudis target military leaders without substantial collateral damage for civilians."

War Powers Resolution

For the senators who pushed the Tuesday vote, the crux of their argument is that U.S. forces aren’t legally allowed to participate in the Yemen conflict.

Article II Section 2 of the U.S. Constitution states that the president “shall be Commander in Chief” of the U.S. military. Beyond that, however, law scholars have not settled on the extent to which the president has authority over the military without a congressional declaration of war.

“As Congress has not declared war or authorized military force in this conflict, the United States’ involvement in Yemen is unconstitutional and is unauthorized,” Sanders said in a floor speech.

The War Powers Resolution was passed by Congress in 1973, following more than a decade of U.S. forces being sent to combat zones in Southeast Asia absent congressional oversight.

The law requires the president to alert Congress when troops are committed somewhere within 48 hours. On top of that, it also requires the president to withdraw troops after 60 days if Congress has not granted an extension, or formally declared war.

Mattis’ letter recognized those restrictions, admitting that no U.S. president authorized the use of military force against Houthi-aligned forces in Yemen. Instead, U.S. support is strictly in the form of “intelligence sharing, military advice, and logistical support, including air-to-air refueling,” he wrote.

That explanation was rejected by those who voted against killing Tuesday’s resolution.

Lee argued that the definition of hostilities is being interpreted too narrowly by the Trump administration and Mattis.

“Suggesting that we’re not in hostilities unless we have people on the ground firing upon an enemy and being fired upon, that is not always the way modern warfare has been conducted, and hasn’t been for some time,” Lee said on the Senate floor. “We have our military personnel engaged in things like mid-air refueling on combat missions ... those combat planes are en route to a battlefield, to a theater of war. If those aren’t hostilities, then I don’t know what is.”

Kyle Rempfer was an editor and reporter who has covered combat operations, criminal cases, foreign military assistance and training accidents. Before entering journalism, Kyle served in U.S. Air Force Special Tactics and deployed in 2014 to Paktika Province, Afghanistan, and Baghdad, Iraq.