When it came time to write down his account of his nearly 40 years in the Pentagon, former Defense Secretary Ash Carter decided to focus on the less glamorous parts of the job, which he served in for the last two years of the Obama administration.

His lessons learned include how to keep wasteful high-dollar programs under control, navigating a fraught relationship with Congress, and why you should never take the military’s top job just because the president asks you to.

“Inside the Five-Sided Box: Lessons from a Lifetime of Leadership in the Pentagon,” released in June, is more of a primer for working in high-level, high-pressure management jobs, which Carter, now a public policy professor at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, told Military Times is exactly how he intended it.

“I said, there are three jobs. One is to advise the president, and most books focus on that. But there are two other jobs, and my book focuses on them,” he told Military Times in a Sept. 27 phone interview. “Second is to execute decisions excellently and the third is to run half the federal government.”

Divided into specific tranches, the book covers defense acquisitions ― Carter’s expertise, as he became the Defense Department’s designated “czar” for that division ― and the F-35 joint strike fighter budget fiasco, the operational decisions that came across his desk he presided over wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, the manpower decisions he signed off on that quite literally changed the shape of the military and more.

"It’s an executive guide to the Pentagon, he said. “I think managers in smaller enterprises can learn something from what it’s like to run the biggest enterprise.”

His biggest challenge, he said, was trying to balance the demands of running a massive organization with the painful reality of the lives forever changed by the consequences of the department’s decisions.

“It’s hard to remember now, maybe, for many people, what it was like in the years when we were suffering heavy casualties,” he said, remembering weekends spent visiting troops and their families in military hospitals, or welcome caskets home at Dover Air Force Base, Delaware.

Eighteen years into the Global War on Terror, and no closer to an end for the war in Afghanistan, Carter offered that it may be wiser to accept that a U.S. presence in that part of the world is as much a benefit as it can be a detriment.

“Well, I really do believe we’ve been on the best course, and the only course available to us,” he said, in the effort to prevent another foreign-planned terrorist attack on American soil. “In order to make sure that terrorism didn’t emanate from there again, we had to build up the Afghan security forces and gradually transfer authority to them.”

It has not gone entirely smoothly, he conceded, but local forces have made enough progress to make staying that course worth it.

“I’m very doubtful of the prospect for reconciliation with the Taliban, and if it’s possible at all, it’ll be when they realize they can never succeed — and I don’t think they’ve been beaten enough militarily to have that realization,” he said.

RELATED

What’s more, he added, a long-term footprint in Afghanistan ― focused on support Afghan troops in stabilizing the country, as well as beating back terror threats like ISIS-K ― otherwise makes strategic sense.

“If we succeed, or when we succeed, we will have a friend and a platform in South Asia. People forget that we couldn’t have killed Bin Laden in Abottabad if he didn’t have territory in Afghanistan to operate from,” he said. “It’s not a bad thing to have a friend in a dangerous part of the world ― just look at a map.”

In his view, he said, the government is more stable and the troops are more capable, and there’s no reason to upend that by making a deal with the Taliban and heading home.

“There are not conditions which make me pessimistic or suggest that it’s time to capitulate to the Taliban,” he said. “One casualty is too many, of course, but it’s nothing like it was five years ago. And I think there’s every prospect that the Afghan security forces can take more and more of the burden, and that the U.S forces will do more of the advising.”

Changing the game

Carter’s time in office was also characterized by a couple of seismic shifts in personnel policy, the biggest being lifting the ban on women serving in direct-combat units.

Former Defense Secretary Leon Panetta had gotten the official ball rolling with an announcement of that intention, in early January 2013, but the integration itself happened in dribs and drabs.

“Previously, the can had been kicked down the road, including by me, when I was deputy secretary of defense,” until a decision in late 2015 to bite the bullet and direct the services to get an integration plan together by Jan. 1, 2016.

Famously, the Marine Corps was the only service who put up a fight, but the military’s highest-ranking Marine told Carter that if he was going to lift the ban, there couldn’t be any exceptions.

It was important to have a joint decision," he said. “And the chairman, [Marine Gen.] Joe Dunford, recommended a joint decision, and that meant there would be no exceptions anywhere.”

Carter said implementation has gone well, from his point of view. Hundreds of women have qualified their way into Army and Marine Corps infantry and armor units, though the high physical standards of special operations organizations have slowed integration there.

RELATED

“Some women are going to be better at some things than some men, and vice versa,” Carter said. “But you can’t hide the fact that culturally and behaviorally and physically, there are differences between women and men. Our studies show that.”

It was more a manpower issue than anything else, he said, because banning women from combat arms meant disqualifying half of the population from filling the biggest specialties in the military, at a time when recruiting was becoming more and more difficult.

“That’s the prize. If you’re running a volunteer military, then you have to attract as many qualified people to military service as you can,” he said. “And I didn’t want to take half the population off the table.”

He also didn’t do it for political reasons, he said, though President Obama was supportive.

“As the book indicates, I didn’t tell the president I was going to do it in advance,” he said, and in fact waited until an hour before his announcement to send word to the White House. “I was willing to take the flack, and I wasn’t looking for the credit, but I wanted it to be a DoD professional talent management decision.”

His decision to lift the ban on transgender service members emerged from a similar policy standpoint, he said, though the population was much smaller.

“The reason that a decision was basically unavoidable was that we had transgender members in service,” he said. “We knew that. Their commanders knew that. And their commanders didn’t want to throw them out, because they were doing a good job.”

It wasn’t fair to leave commanders, especially the younger, company grade officers who had the closest relationships with their transgender troops, with murky guidance as to how to handle them. As long as they were meeting standards, there was no reason to kick them out.

“And then, if you decide you’re not going to throw out the transgender members who are there, there’s no argument for not admitting more,” he said.

Except, he added, the cost of medical care for transitions. Along that vein, DoD crafted a policy to cover transitions for existing service members, but limited accessions to recruits who had already completed their transitions.

“It is military qualifications and the ability make standards that will guarantee that we continue to have the finest fighting force in the world,” he said. “Anything else is social policy, and there’s no place for social policy in the military.”

The Trump administration, of course, did not share his sentiment. In July 2017, President Trump tweeted that he intended to re-instate the ban. The accessions policy was scrapped, though currently serving troops have been allowed to stay. The policy itself has been ping-ponging through the judicial system ever since.

“It seemed to have been done abruptly, without the department’s input,” Carter said. “But I think that history will come around again and re-establish the original policy. I really do.”

Sticking up for your people

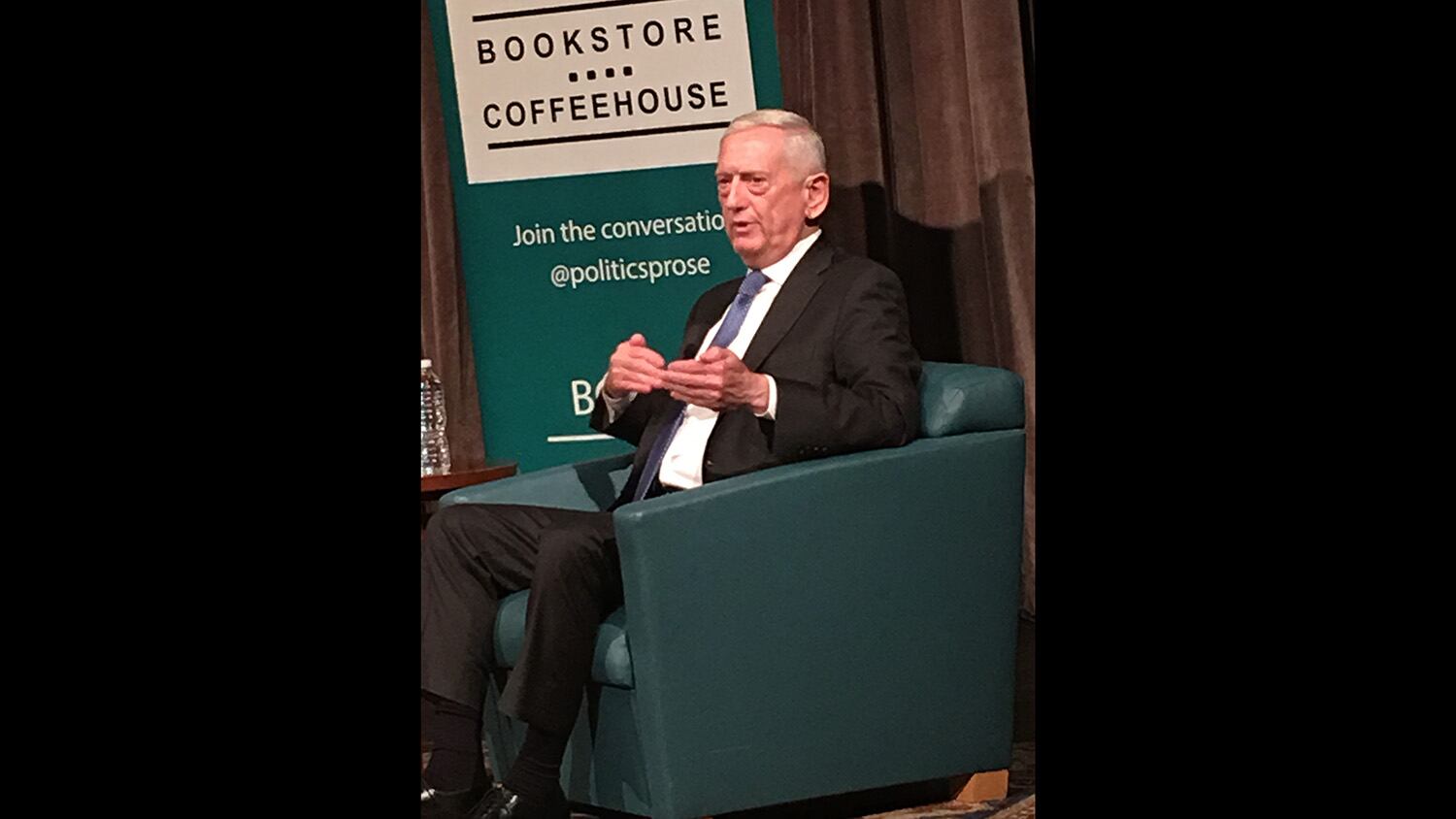

It’s been nothing short of a rocky year at DoD. Trump’s original pick for defense secretary, retired Marine. Gen. James Mattis, stepped down at the end of the year, citing irreconcilable policy differences with the president.

“I don’t see Cabinet members being listened to, which is something I’ve never witnessed in all my years,” Carter said.

Without naming names, he explained the risk of taking a high-level political post based on a sense of duty.

RELATED

“I say that because there’s a myth around that, if the president calls you, you should say yes. That’s a mistake,” Carter said. “Your duty, in that circumstance, is to ask yourself, ‘Can I really help the president in that job?’ And if you believe that instead you’re going to go in and every day is going to be trying to manage differences, you’re not going to be helpful to him.”

One shouldn’t expect to win every disagreement with the president, he added, but a defense secretary should feel as if his or her counsel is being considered.

“At the moment, what I see is that the department, under these circumstances, is having difficulty walking into the future in the way that we need to do to compete with Russia, China, and so forth. And has fought off politicization and abuse of the chain of command and so forth,” Carter said.

The situation is disturbing, he said, but DoD is resilient, and full of the best people at what they do, capable of weathering the storm and bouncing back.

Mattis’s deputy, Patrick Shanahan, assumed the acting role and was preparing to fleet up following a confirmation hearing when, in June, details of his nasty divorce hit the Washington Post, and he, too, decided to pack it in.

Trump then turned to Army Secretary Mark Esper, who was confirmed in July after a whirlwind nomination and a bit of legal hot potato to keep his seat warm while he got on the Senate’s calendar for his own confirmation hearing.

“In the book, I talk about the two sides of leadership,” Carter said, when asked how that kind of turmoil affects the thousands of civilians working for the department. “One is leading into the future. And that requires somebody at the top. And so the department can tread water without senior leadership, but it can’t move into the future without senior leadership. That’s not the way it works.”

Now that the management situation is stabilized, he added, it’ll be up to Esper to have those service members and civilians’ backs.

“Stick up for the institution and for its values and its honor and its excellence. And from the point of view of the soldier, sailor, airman or Marine, or civilian, or officer looking up, they need the boss to reinforce right or wrong,” he said. “They know the right thing to do. Our people our excellent. But they need someone to stick up for them against politicization, un-careful use of the military ― or non-use of the military ― that is giving ground to enemies.”

Meghann Myers is the Pentagon bureau chief at Military Times. She covers operations, policy, personnel, leadership and other issues affecting service members.