By 1944 the United States had entered its fourth year of the Second World War. The invasion to retake Europe had begun June 6, and the American public was transfixed by its military forces clawing back Europe from the clutches of Nazi Germany.

Amid this backdrop came the game of the century that, albeit briefly, delivered a respite from the far-flung battles across the globe and drew attention back to a good, old-fashioned American football rivalry.

“The Army-Navy game symbolized the continuation of peacetime rivalries in a time of national crisis,” author Randy Roberts wrote in “A Team for America: The Army-Navy Game That Rallied a Nation at War.”

“In a very real sense, it stood for exactly what Americans most desired, a return to the normality of American life.”

Yet the matchup almost didn’t happen. A little less than three years earlier, when the Japanese assault on Pearl Harbor plunged the U.S. into World War II, there were calls from politicians and those within the military for Americans to set aside peacetime frivolities, according to the Wall Street Journal.

“You can’t train a man to be a fighter by having him play football and baseball,” said Cmdr. James Joseph “Gene” Tunney, the Navy’s director of physical training and boxing’s former heavyweight champion. College football, he said, “has no place in war or preparing for war.”

Others disagreed.

“The British are going all out for sports as a morale builder, despite their proximity to the Luftwaffe and robot bombs,” Rep. Samuel A. Weiss, D-Penn, said in 1944. “Why, they have scheduled sixty-five sports events over there, thirteen of them major events expected to draw between 65,000 and 125,000 people. Our government realizes that if the British feel the need for public sports events so keenly, we certainly ought to do the same thing when we’re practically out of danger here.”

Cmdr. Thomas J. Hamilton, the head of the Navy’s Pre-flight and Physical Training program and a former head coach at Annapolis, felt similarly to Weiss, and, since he had the ear of much of the military brass, managed to shoehorn collegiate sports back on the menu.

The war itself had been a boon to both of the service academies’ football programs.

According to SB Nation, a dismal 1-7-1 record in 1940 prompted the United Press to describe the U.S. Military Academy Cadets as “a national calamity,” and military officials seriously considered mothballing the football team.

However, due to the war, the widespread influx of young men into the ranks of the U.S. military meant a swell of talent.

Further still, West Point, determined to snap its five-game losing streak against the U.S. Naval Academy Midshipmen, hired Earl “Red” Blaik in 1941, who was, according to SB Nation, “spartan and abstemious by nature.” His most profane epithet was a blistering “Geez, Katy.”

Yet his soft-spoken manner belied spectacular football acumen. His insistence on clean fundamentals and timing earned him the title of “that metronomic drill devil,” but his team was the better for it.

Interest in the game, originally set for Dec. 2, 1944, at the Naval Academy’s 12,000-seat stadium, swelled, with the rivalry matchup relocating to the 66,000-seat Municipal Stadium in Baltimore just a mere two weeks before kickoff. Tickets sales went toward war bonds and sold out in 24 hours, raising $58.6 million for the war.

One of the country’s preeminent sports writers at the time, Grantland Rice, wrote that it would be “one of the best and most important football games ever played.”

Army entered the contest with an undefeated 8-0 record, while Navy, coached by Cmdr. Oscar Hagberg, who had just returned from a Pacific submarine command, came in at 6-2.

Led by running backs Felix “Doc” Blanchard and Glen Davis — known as Mr. Inside and Mr. Outside, respectively — Army had decimated their opponents throughout the 1944 season, outscoring them 481-28. In fact, their last defeat had come in 1943 — at the hands of the Midshipmen.

Not to miss out on the spectacle was that of Army Chief of Staff Gen. George C. Marshall, Gen. Hap Arnold, commander of the Army Air Forces, and Adm. Ernest King, chief of naval operations.

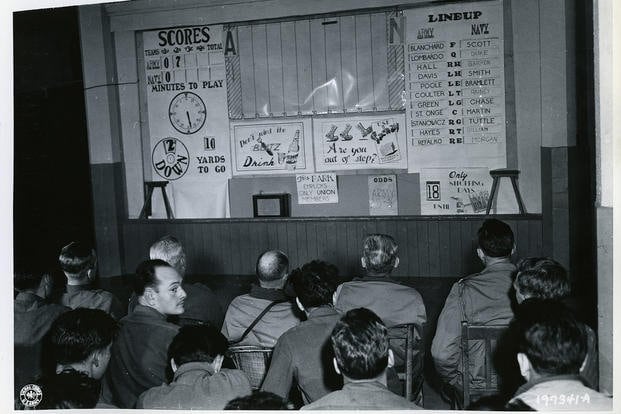

And, while not televised — that would come the following year when Army was ranked No. 1 and Navy No. 2 — the eyes and ears of millions of Americans at home and abroad turned their attention from the battlefield to the gridiron.

“Win for all the soldiers scattered throughout the world,” came the pregame telegram from Army Gen. Robert Eichelberger, a former West Point superintendent stationed in the South Pacific.

Both teams entered the field that day in spectacular fashion, with the Navy contingent sailing across the Chesapeake Bay to arrive at the field, while the Army men were carried in on troopships escorted by Navy destroyers.

Winning the toss and electing to kick off, the Cadets struggled to get anything going offensively in the first quarter. So too did the Midshipmen. However, the defensive slog, noted New York Times sportswriter Allison Danzig, meted out “unusual ferocity of the give and take.”

By the end of the third quarter it was a mere 9-7 with Army in the lead after a safety. The game finally broke up in the fourth quarter with Army scoring two more touchdowns to win 23-7 against their archrival.

Despite throwing five interceptions and fumbling the ball three times, Army kept control, outgaining the Midshipmen 181-71 on the ground with Navy only completing 14 of 24 passes for 98 yards.

“It’s just about the best Army team that I have ever seen,” said Hagberg between bites of a post-game ham sandwich. “Our offense just couldn’t get going. They whipped us, and that’s just about all there is to it.”

“I think it was just a case of the No. 1 team in the country beating the No. 2 team in the country,” Blaik stoically stated in the aftermath.

Gen. Douglas MacArthur, supreme allied commander of the Southwest Pacific Area, was much less impassive in his praise, famously wiring Blaik: “The greatest of all Army teams. … We have stopped to war to celebrate your magnificent success.”

Claire Barrett is an editor and military history correspondent for Military Times. She is also a World War II researcher with an unparalleled affinity for Sir Winston Churchill and Michigan football.